Network Architecture Security Plan

Network Architecture Security Plan Proposal

Section 1: Introduction

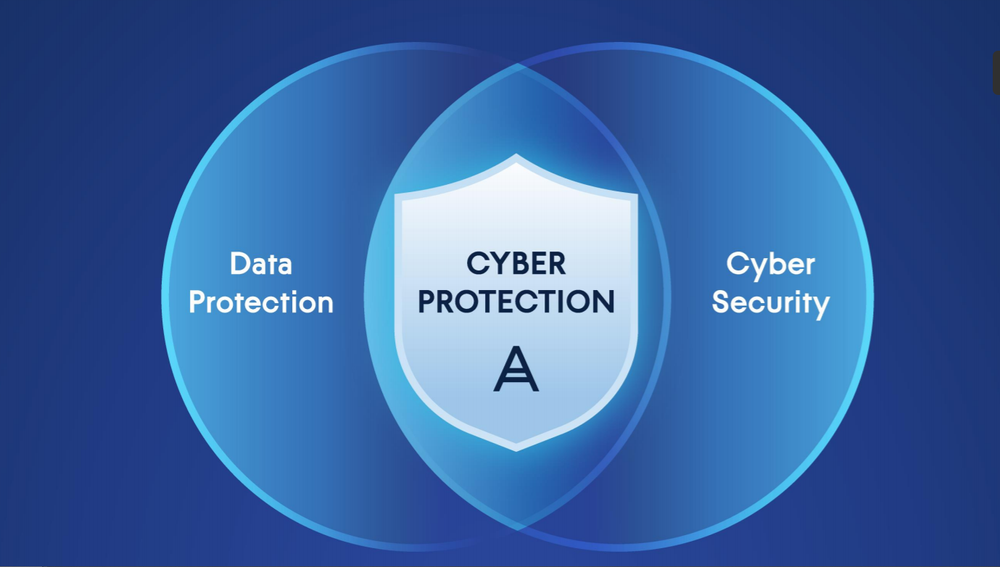

Cyber threat protection for any business and its data is a challenging task requiring expertise and well-managed resources. Businesses need a thorough security plan outlining how to protect their network from online threats. Also, the company’s end users want guidance on effectively using mobile platforms, email, the internet, and other network components. However, this approach should not conflict with the business model and should be relatively easy for the personnel to implement (Xu et al., 2022). The network security plan is a strategy that outlines the techniques and policies that will be used to protect the network from unauthorized users and counteract actions that could jeopardize or compromise a system’s security.

Banks are vulnerable to cyber-attacks and require robust network architecture security plans to protect client data and the valuables entrusted to them. JPMorgan Chase collects personal information when clients or customers visit their premises or use their online services, including names, email addresses, mailing addresses, telephone numbers, account numbers, location information, such as zip code, and user name and password for online services. When more personal information is needed for ordinary business purposes, JPMC also collects payment card information, Social Security numbers, driver’s license numbers, and gender, race, nationality, and biometric data (JPMorgan, 2018). The organization also creates personal information for clients in some circumstances, including recordings of customer interactions and account details. Additional information JPMC collects includes device IP address when using online services, operating system and browser type, and information on sites visited and those to be called.

Moreover, JPMC uses customer data regarding social media usage and credit reporting agencies (JPMorgan, 2018). Often cyber-attacks target this information to access consumer bank accounts and other money storage or transfer avenues. Personal information on location, name, and gender can also be used for malice, including targeted attacks on individuals or stalking. This sensitive information needs protection from unauthorized access, loss, or misuse.

This paper seeks to analyze JPMorgan Chase’s network architecture and develop a network security plan proposal that can help the organization further protect public data from security threats. The JPMorgan Chase Institute takes pride in offering insightful information to decision-makers in government, business, and charitable organizations (JPMorgan Chase & Co, 2022). These disclosures, however, must not come at the expense of client or customer confidentiality. To achieve this, the Institute has implemented stringent security procedures and checks and balances to guarantee that all consumer data remains private and secure (JPMorgan Chase & Co, 2022). Government agencies use of statistical standards and JPMorgan Chase’s collaboration with technology, data privacy, and security specialists who are assisting the enterprise in upholding industry-leading standards have all influenced these measures.

Currently, the enterprise adopts measures as a further commitment to protect public data and ensure privacy and confidentiality, including the Institute’s standards and procedures that mandate that any data it collects and uses for various purposes not contain any personal information about clients. Before accessing client data, the Institute also makes its researchers and employees submit to thorough background investigations and sign binding confidentiality agreements (JPMorgan Chase & Co, 2022). Employees are legally obligated to only utilize the data for authorized purposes and not try to re-identify any clients or individuals reflected in the data. Any publishing derived from Institute data is required only to include aggregate data or data that is not otherwise not reasonably traceable to a specific, identified consumer or business. The information that the JPMC and its staff rely on is kept on a secure server that is only accessible per stringent security guidelines intended to prevent the transfer of information outside of JPMorgan Chase’s systems (JPMorgan Chase & Co, 2022). All JPMorgan Chase Information Technology Risk Management specifications for data monitoring and security are met by its data infrastructure.

The security plan proposal offers insights into strategies and procedures JPMC can adopt to reinforce or ensure better data protection and promote customer privacy and confidentiality due to the growing hacker threat probing organization networks. The plan seeks to help the enterprise to protect the network infrastructure from unauthorized access, data misuse, destruction, and damaged corporate reputation. The plan will offer recommendations to the enterprise for dealing with suppliers and dependent subcontractors and their access to information classification to ensure data protection. It will also advise additional measures for data protection, data encryption to protect data in transit, authentication approaches, protection policy, digital signatures, random number generation, hash functions, and key and certificate lifecycle management.

Moreover, it will offer procedures for data protection policy review and cookie management procedures that should comply with applicable laws and regulations. Furthermore, the security plan proposal will include recommendations on identity and access management, security configuration procedures, security operations, vulnerability management, and third-party relationship management and access protocols. Generally, this paper aims to describe the JPMC network architecture and offer a plan for managing and protecting data, risk assessment, digital evidence controls, computer forensic analysis, and recovering files, and provide recommendations for best practices.

Section 2: Network Architecture

The Network Architecture for JPMorgan Chase & Co.

JPMorgan Chase & Co is a financial institution in the US in the consumer or commercial banking category. It offers financial services and advice to millions of people and maintains a wide variety of consumer data that needs protection from unauthorized access or illegal use. The bank adopts the client-server network architecture in which people can access information stored in its server via various platforms, including its website and other online services. This architecture allows individuals to access shared files and information, which are centralized, with a backup, from their serving machines like mobile devices and computers, which include the teller computers (Sugandhi, 2023). More than one client has access to resources and services, and there are different servers, including mail, web, and file servers. The client-server relationship is one-to-many because multiple clients can access the services and resources at go. The JPMorgan Chase & Co bank has moved into an almost entirely digital locale, and most clients or users access its resources and information remotely.

Considering the bank serves thousands of customers daily requesting different services and constantly trying to access information and bank services at high speeds through their virtual devices, client-server has been the heart of its banking system because it works effectively and makes it easy to manage information and service delivery centrally. With this architecture, the bank keeps a centralized record of all the information needs, including account information, that can be accessed at the banking center by a teller or from remote devices. Generally, an account holder can check balances, withdraw money, or deposit money. Additional services include financial advice, questing for a loan, servicing a loan, or asking for bank statements. JPMorgan Chase & Co bank network architecture is vast, with multiple serves and databases at the center of the architecture, providing additional functionality to its customers. According to (Sugandhi, 2023), this centralization allows consumers to access resources and services without the need to understand how many servers they are communicating with, increasing the possibility of breaking down the architecture to even pore task-particular nodes and elevating the distribution of the application task and processing to ensure greater performance, reliability, and security.

The servers are under strong server standards that guide the core functionality of the client-server relationship, ensuring it is more static, enabling the bank to upgrade by extending the model into future devices not used before, like mobile banking applications, without the need to redesign the architecture. As the industry and the bank mature, this architecture that allows an extension allows the bank to keep up with new customer demands for increased functionality, performance, security, and flexibility of the banking system. Generally, the client-server architecture has seamlessly transitioned the bank into the digital world of virtual services.

Figure 1: Client-server architecture model used by JP Morgan Chase & Co.

Physical Structures, Major Types of Hardware Used to Connect Computers and Networks Together, and the Way Data Travels Through the Network

Different types of hardware connect the computers and the network in the client-server architecture. The three major interrelated components are workstations, servers, and networking devices. Workstations are also client computers or mobile devices with different operating systems, mostly lacking administrative or security policies, a centralized database, or shared software. Servers hold much information and handle multiple requests, having more memory, hard drive space, and faster speeds (Hill et al., 2017). Servers have multiple roles, acting as the domain controller, mail server, file server, and database server, all running simultaneously. These duties are assigned to different servers to maximize performance and simplify maintenance and backup (Hill et al., 2017). Some networking devices connect computers and the network, including hubs that connect a server or centralized servers to many different workstations, repeaters that help transmit data from one device to the next, and bridges that segment isolated networks.

The primary purpose of adopting the client-server architecture is to speed up data transmission and protect data during transfer. It makes the ban faster and more secure regarding data transfers. In most instances, the interaction begins with a client request to the server through the internet, and it is successful when the server accepts the request and returns the information or data packets the client requested (Hill et al., 2017). Generally, a client sends a request to the Domain Name System (DNS) server, which searchers for the specific server and replies with the details, including the IP address of the server to the client, then the browser sends an HTTP(S) request, if the request is through the web, to the server’s IP address (Hill et al., 2017). A successful and accepted request sees the server send the necessary files, and the browser displays them to the client.

Figure 2: Network Connectivity of JPMorgan Chase and Co.

JPMorgan Chase & Co has a data mesh architecture that aligns its data technology to its data product strategy. This data mesh architecture is beneficial as the bank adopts cloud services, enabling data sharing across the institutions while allowing data owners more control and visibility of their data, which increases the ability to manage their data effectively (Jain et al., 2022). The significant advantages of the data mesh are the ability to align the data architecture to the data product strategy, empower the right people or data owners to have more control and make control decisions, enforce control decisions via in-place consumption, and offer cross-enterprise visibility of data usage or consumption. The data mesh makes data available in lakes, and individuals can request the lake-based data via a reporting application (Jain et al., 2022). The bank can audit data flows from the lake to the reporting application, increasing visibility or clarity of the origin of the data in the reports.

Figure 3: JPMC & Co Data Mesh

Section 3: Managing and Protecting Data

Deploying a network security policy is a critical undertaking to prevent security issues on the network. A network security policy provides guidelines for network access, determines policy enforcement, dictates the organization’s network security environment, and provides how security policies are adopted throughout the network architecture (Valenza et al., 017). Security policies are the organization’s security control on various components of the network architecture, keeping malicious individuals from accessing the network and mitigating risky people within the organization. The first or initial provision of network security policy is regarding access to information, including what information and services are available, to whom, and through what means, and the protection needed. A hierarchy of access permissions ensures that individuals at different levels can only access what they need to operate with. The proposal recommends the following policies for managing and protecting data:

User Access to Computer Resources

It is critical to protect organization computing systems and resources by implementing user access security activities and ensuring users have the right to access the information they need to work with. A user access security policy is needed to control user access to computer resources, ensuring that only authorized users can access particular resources. The acceptable use policy (AUP) stipulates the rules, practices, and constraints users must agree with to access the organization’s network, internet, and other resources (Kirvan, 2022). Employees must sign the AUP before being given permission or a network ID. The AUP provides users with instructions on what they can or cannot do when using the organization’s computers, computing infrastructure, and the internet. Moreso, this applies to tellers and other office employees that have been provided individual computers for use within the organization. It spells out acceptable and unacceptable behavior and will offer the organization legal mechanisms to ensure compliance and repercussions for non-compliance.

Security Profiles

A security profile is attributed to an organization’s overall security program, comprising security determined by the organization’s work and the network facilities in place. It dictates the network, log sources, and domains a user can access (IBM, 2023). Individuals at different access levels will have different security profiles; for instance, administrative users will have a default security profile that provides access to all networks, log sources, and domains. The organization will create more security profiles before adding user accounts to help meet specific access user requirements. The security profiles policy will help configure security profiles at run-time to dictate or control security operations completed in a message flow at run-time. The security profiles policy will help determine authentication and authorization on source identities.

Passwords

In a secure network, users need passwords to access network resources. However, the organization must follow the rules regarding passwords or policies it should share with users to dictate password development to ensure a secure and protected network. A password management policy provides the organization’s requirements for acceptable password options and maintenance. The policy guides password creation to maximize password security and minimize password misuse and theft. For this proposal, all passwords should be strong and contain at least eight alphanumeric characters, at least two non-alphabetic characters, and at least three alphabetic characters (Shay et al., 2016). Also, the password should not be a single dictionary, language, slang, dialect, jargon word, or personal information. However, individuals can develop passwords with passphrases that contain three or more dictionary words joined by alphabetic characters. All passwords are private and should not be written or stored online, shared within an email message or any electronic communication, shared with anyone, including other organization personnel, or be the same as those used to access external accounts like online banking. Users should change their passwords at least every six months. Lastly, any passwords suspected of being compromised should be changed promptly.

Email

Most hackers or malicious users use email conversations to access personal information or have users click on malicious links without suspecting it. An email security policy is needed to govern email use within the organization’s network. The policy provides how the users will interact with email messages to ensure that email messages are secure from unauthorized access (Wilton, 2021). The email security policy requires the organization to use trusted email services like Gmail that include capabilities like regular updates, improved phishing filters, and multi-factor authentication, create effective spam filters, educate users to sport phishing emails and malicious attachments and links, and protect email address by instructing users and employees not to post work email addresses on social media accounts or other public platform and adopt catchall email for customer services and support.

Internet Access

An internet security policy allows the organization to manage internet access and comply with federal, legal, and accreditation rules and requirements on internet and data confidentiality and integrity. The policy dictates that users should not access or use the organization’s internet for personal business, have a valuable purpose for accessing and using the internet, and avoid offensive websites and pornographic content. Additionally, users should not use another individual’s network ID, password, or other identification details to access the internet, establish external network connections, or new network connections to allow communication or unauthorized access to the network without the Security Officer’s approval. Users are also required to avoid transferring identifiable information through the internet.

Antivirus

All users must adhere to the antivirus policy, which requires all users connected to the network or data systems to have antimalware software installed and authorized and qualified IT personnel to conduct a comprehensive analysis of virus threats regularly and evaluate application software for adequacy and sufficiency (Trinity University, 2022). Also, all resources with an antivirus installed need regular updates, and the antivirus selected must scan email, email attachments, web traffic, media, and downloaded files. Infected devices should be disconnected immediately, and the virus should be removed. Users must not install unauthorized software from external networks.

Backup

The backup policy requires all organization data and resources to be backed up as a data protection, disaster recovery, and business continuity plan. The policy also ensures that all organization and user data copies are safe (Savannah State University, 2016). It provides the organization to back up data on the cloud for rapid recovery in case of disruption. The policy dictates what data needs protection, where to store the copies, how often the backup should run, and the time to retain a copy. The policy adopts the 3-2-1 approach that requires the organization to have three backup copies in two locations, one on the cloud and the other in an offsite location. The organization should have an incremental backup that copies the data sets that have changed since the previous backup.

System Patches

The system patch management policy highlights the processes and approaches that help ensure that hardware and software on the organization’s data are regularly maintained (Jill, 2022). The patching security policy requires patches to be evaluated constantly and responded to promptly, documented and well understood by employees, automated and constantly monitored, and executed according to the vendor tools on a constantly communicated schedule.

Remote Access

Employees and consumers can access data remotely or offsite, which sometimes increases the risk of unauthorized users like hackers and man-in-the-middle accessing the data (Ouaddah et al., 2016). The remote access policy requires individuals accessing the organization’s services remotely, especially employees, to have standardized hardware and software, including firewall and antivirus or antimalware, to adopt data and network encryption standards, use VPN access on network connectivity, and follow information security and confidentiality and email usage policies.

Intrusion Detection

Intrusion detection or prevention and a security monitoring policy are vital in monitoring loggings and observing events to identify security issues and threats. Internet, electronic mail, Local Area Network traffics, and operating system security parameters will be used to monitor intrusions. Intrusion checks will monitor the firewall, automated intrusion detection system, user account, network scanning, system error, application, data backup ad recovery, telephone call, service desk trouble tickets, and network printer logs for any signs of vulnerability (Sam Houston State University, 2022). Every year, the policy requires checking password strengths, unauthorized network devices, unauthorized personal web servers, unsecured sharing of devices, and operating system and software licenses.

Section 5: Digital Evidence Controls, Computer Forensic Analysis, and Recovering Files

Preserving Information for Forensic Analysis

Digital evidence can be stored and maintained in physical or digital devices. After information collection, it will be moved to physical media for storage and where it can be accessed. The data acquired and the device used for storage are secured until the information is required for forensic analysis. The physical and digital storage systems or a smart management system are integrated to form the evidence management system to be used at the organization. Preservation is required to ensure the legal admissibility of the information stored. The evidence management system will include drive imaging, hash values, and a clear chain of custody (Simon, 2023). Rather than the original information, the company will create images of the evidence that will be used for analysis. The analyst will develop a duplicate of the drive used to store the information to help retain the original evidence for investigation. Investigators can exclusively use the duplicate image rather than the original media.

Hash values will also aid in preserving the evidence or information generated when duplicates or images of the original media are produced. The hash values will help determine the authenticity and integrity of the duplicates as an exact image of the original information. Hash values will help ascertain if the information was altered at any point, which is a vital part of forensic analysis and admitting the evidence in court if necessary (Simon, 2023). Creating new or editing existing files generates new hash values that can only be accessed using special software. The hash values must match the expected values, and if not, they will help confirm that the evidence was altered. A clear chain of custody is vital in digital evidence preservation. The company forensic analyst or investigator will document all media and evidence transfers on the Chain of Custody (CoC) forms and capture signatures and dates after handing off media. The chain-of-custody paperwork will help determine that the image of the digital evidence is or was under known possession from the time the duplicate or image was created (Simon, 2023). A lapse in the chain of custody would allow the company to nullify the legal value or dependability of the image. Generally, the primary purpose of preserving the evidence is to ensure legal admissibility.

Digital Evidence Controls

JP Morgan Chase works with a cybersecurity forensic investigator whose main role at the company is to watch over the data and find innovative ways to protect the data. Approaches used to control digital evidence include risk reviews and vulnerability analysis that help identify potential threats. The investigator conducts forensic preservation work and preliminary investigations, adopting established standards (JP Morgan Chase Company, n.d.). The investigator also helps identify violations of the JP Morga Chase Code of Conduct and identifies, collects, and preserves the associated digital evidence. The organization, through the investigator, conducts forensically sound collection and analysis of electronic evidence using different tools to enhance security, compliance, and legal processes.

JP Morgan Chase preserves network and host-based digital forensics on Microsoft Windows-based systems and other necessary operating systems like LINUX and adopts standard digital forensic and network monitoring tools to independently plan and carry out forensic support. The organization adopts High-Security Access (HSA) systems for forensic investigations. It conducts an enhanced annual screening of users of the systems, including checking criminal and credit backgrounds (JP Morgan Chase Company, n.d.). Additionally, the organization ensures technology governance, risk, and compliance by regularly validating the effectiveness of the controls, assessing risk annually to ensure the implemented controls can protect the organization’s information, and adopting security policies and procedures to govern receipt, transmission, processing, storage, retrieval, access, and presentation of the information. The principle of least privilege is adopted to grant personnel access to the information. Physical facilities hosting the data are restricted and have detective monitoring controls and controls for hazards like fire and water.

Computer Forensic Tools for Forensic Analysis and File Recovery

The autopsy/the Sleuth Kit will be used for disk analysis. The tool is recommended for its ease of use, extensibility, speed, and cost-effectiveness. The Sleuth kit is a command-line tool that helps conduct forensic analysis of hard drives and smartphone images. The Autopsy is a GUI-based system using the Sleuth Kit in the background (Kaushik et al., 2020). Its modular and plug-in architecture ensures that the user can easily incorporate additional functionality. Law enforcement agencies and organizations can use this tool to investigate activities or events in a computer, analyze disk images, and recover associated files. The tool can analyze both Windows and LINUX disks. The Volatility tool will also help with memory forensics, incident response, and malware analysis. Often, investigations determine what activities occurred at the time of the incident. Volatility is used to link device, network, file system, and registry artifacts to confirm the list of all running processes, active and closed network connections, running Windows command prompts screenshots and clipboard contents that were in progress at the time of the incident (Mohanta et al., 2020). Investigators will use Volatility to assess processes, check command history, and retrieve files and passwords from the system.

Section 6: Recommendations for Best Practices

Recommendations For Best Practices

The organization must understand the OSI Model, different types of network devices, network defenses, network segregation, proper placement of security devices, network address translation, avoiding disabling personal firewalls, centralized logging, and immediate log analysis as best practices for network security. The organization should comprehend the devices that make up the network in order to build and protect it (Yu et al., 2019). Hubs, switches, routers, bridges, and gateways are the various categories of network devices. Also, the company may protect its network by implementing the right tools and solutions. Firewalls, intrusion detection systems, intrusion prevention systems, network access controls, web filters, proxy servers, anti-DDOS, load balancers, and spam filters are among the most popular and efficient network defenses.

Network segmentation includes dividing the network into zones, which are logical or functional components. For instance, the company might have distinct technical requirements for its sales, technical support, and research zones. It can do this by employing switches, routers, or virtual local area networks (VLANs), which are made by setting up a switch’s ports to act like different networks (Netwrix Corporation, 2022). Segmentation restricts the scope of what could be affected by a compromise to that particular area. In essence, it separates one target into several, giving attackers the option of treating each part as a separate network or compromising one and trying to cross the gap. Neither option is desirable. Since the attacker must breach each section separately, treating each segment as a separate network entail much more work and significantly increases the attacker’s risk of being found. Attempting to jump from a compromised zone to other zones is challenging. The network traffic between the segments can be limited if properly constructed (Netwrix Corporation, 2022). Data classification and data protection also benefit from segmentation. Each segment may be given a different set of data categorization rules, configured to the proper level of security, and after that, monitored.

The company must choose where to put each device as it develops its network segregation strategy. The firewall is the simplest device to install; the company should install a firewall at each network zone intersection (Anwar et al., 2021). A firewall ought to be installed on every section of the network. All current switches and routers have firewalls (Anwar et al., 2021). These features only need to be enabled and properly configured by the company. An anti-DDoS device should also be placed on the perimeter so that the company can thwart DDoS attacks before they spread throughout the network. The company should have a web filter proxy behind the primary firewall that serves the public network.

Another network security best practice is using network address translation. The company can make up for the IPv4 networking address shortage via network address translation (NAT). Private addresses (internal to a specific business) are converted into routable addresses on open networks like the internet through NAT. For instance, NAT is a technique for using a single IP address to link numerous computers to the internet or any other IP network (Netwrix Corporation, 2022). NAT works with firewalls to add an additional layer of protection to an organization’s internal network. The protected networks’ hosts typically have private addresses that allow them to connect with the outside world, but external systems must pass through NAT boxes in order to access internal networks. Additionally, the company can adopt centralized logging and immediate log analysis. The company should keep track of erroneous computer events like logins and other suspicious activity (Netwrix Corporation, 2022). With the aid of this best practice, the business will be able to reconstruct what took place during an attack and take action to enhance its threat detection system and effectively stop attacks in the future.

Why the Proposal Should be Accepted as Best Practices for the Organization

Financial institutions are a lucrative target for cybercrime and network infiltration because of the money. Individuals working outside and inside the banks will likely take advantage of the many vulnerable links in the network architecture and security chains. JP Morgan is a financial institution that is highly vulnerable to security attacks as hackers and malicious individuals seek to access financial account information. This proposal offers a robust analysis of JP Morgan Chase Network Architecture, data management and protection, risk assessment, digital evidence controls, computer forensic analysis, and file recovery, and recommends best practices to ensure network security. The proposal seeks to help the company be more secure by integrating technology and awareness best practices because more than technology is needed to solve network security issues and the cybercrime problem efficiently and effectively. It provides insights into how the company can ensure consumer and organization data security through data management and protection and risk assessment techniques. Most importantly, it suggests to the organization how to protect itself from insider threats by adopting detection strategies, multi-factor authentication, and other preventative measures like system hardening and monitoring of users and networks. These insights are adequate to convince JP Morgan Chase to accept this proposal.

References

Anwar, R. W., Abdullah, T., & Pastore, F. (2021). Firewall best practices for securing smart healthcare environment: A review. Applied Sciences, 11(19), 9183.

Hill, J.D., Kruth, A. R, Salisbury, J., & Varga, S. (2017). Software architecture in banking: A comparative paper on the effectiveness of different software architectures within a financial banking system. https://www.rosehulman.edu/class/csse/csse477/handouts_377/HillTermPaper_FINAL.pdf

IBM. (2023). Security profiles. https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/qsip/7.4?topic=management-security-profiles

Jain, A., Person, G., Conroy, P., & Shankar, N. (2022, May 5). How JPMorgan chase built a data mesh architecture to drive significant value to enhance their enterprise data platform. Amazon Web Services. https://aws.amazon.com/big-data/how-jpmorgan-chase-built-a-data-mesh-architecture-to-drive-significant-value-to-enhance-their-enterprise-data-platform/

Jill, S. (2022). Patch management policy. https://www.cde.state.co.us/dataprivacyandsecurity/patchmanagementpolicy

JP Morgan Chase Company. (n.d.). Cybersecurity Forensic Investigator. https://www.wayup.com/i-Financial-Services-j-JP-Morgan-Chase-Company-827769314821227/

JP Morgan Chase Company. (n.d.). JPMorgan Chase & Co. Minimum Control Requirements. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/documents/supplier-minimum-control-requirements.pdf

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2022). JPMorgan Chase & Co. Minimum Control Requirements. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/documents/supplier-minimum-control-requirements.pdf

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2022, March 29). Data Privacy Protocols. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/about/data-privacy-protocols

JPMorgan. (2018, May 21). Private Policy. https://www.jpmorgan.com/privacy

Kaushik, K., Tanwar, R., & Awasthi, A. K. (2020). Security tools. In Information Security and Optimization (pp. 181-188). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Kirvan, P. (2022). Acceptable use policy (ATP). https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/acceptable-use-policy-AUP

Mohanta, A., Saldanha, A., Mohanta, A., & Saldanha, A. (2020). Memory Forensics with Volatility. Malware Analysis and Detection Engineering: A Comprehensive Approach to Detect and Analyze Modern Malware, 433-476.

Netwrix Corporation. (2022). Network security best practices. https://www.netwrix.com/network_security_best_practices.html

Sam Houston State University. (2022). Intrusion Detection/Prevention and Security Monitoring Policy: IT-23. https://www.shsu.edu/intranet/policies/information_technology_policies/documents/IT-23IntrusionDetectionSecurityMonitoringPolicy.pdf

Ouaddah, A., Abou Elkalam, A., & Ait Ouahman, A. (2016). FairAccess: a new Blockchain‐based access control framework for the Internet of Things. Security and communication networks, 9(18), 5943-5964.

Savannah State University. (2016, July 1). Information Technology Security Plan Backup Policy (10.13). https://www.savannahstate.edu/computer-services/docs/policies-2017/10_13%20Backup%20Policy.pdf

Shay, R., Komanduri, S., Durity, A. L., Huh, P., Mazurek, M. L., Segreti, S. M., … & Cranor, L. F. (2016). Designing password policies for strength and usability. ACM Transactions on Information and System Security (TISSEC), 18(4), 1-34.

Simon, M. (2023). Methods to preserve digital evidence for computer forensics. https://www.criticalinsight.com/resources/news/article/3-methods-to-preserve-digital-evidence-for-computer-forensics

Sugandhi, A. (2023). Client Server Architecture: Components, Types, Benefits. https://www.knowledgehut.com/cloud-computing/client-server-architecture

Trinity University. (2022, June 16). Antivirus policy. https://policies.trinity.edu/a2e92e93-3e56-45ac-b237-da061062f925.pdf?v=mM8K9Ed4AUOdCX0xEXykCQ2/

Valenza, F., Su, T., Spinoso, S., Lioy, A., Sisto, R., & Vallini, M. (2017). A formal approach for network security policy validation. J. Wirel. Mob. Networks Ubiquitous Comput. Dependable Appl., 8(1), 79-100.

Wilton, L. (2021). How to secure email in your business with an email security policy. https://carbidesecure.com/resources/how-to-secure-email-in-your-business-with-an-email-security-policy/

Xu, J., Sun, F., & Chen, Q. (2022). Network security. An Introduction to the Smart Court System-of-Systems Engineering Project of China (pp. 343-384). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Yu, Q., Ren, J., Fu, Y., Li, Y., & Zhang, W. (2019). Cybertwin: An origin of next generation network architecture. IEEE Wireless Communications, 26(6), 111-117.

Do you need a similar assignment done for you from scratch? Order now!

Use Discount Code "Newclient" for a 15% Discount!