Nursing Paper Example on Kawasaki Disease

Nursing Paper Example on Kawasaki Disease

Nursing Paper Example on Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease is an acute, self-limited vasculitis predominantly affecting children under five years old. It is one of the leading causes of acquired heart disease in children in developed nations. Characterized by systemic inflammation of medium-sized arteries, particularly the coronary arteries, Kawasaki disease poses significant risks if untreated, including coronary artery aneurysms. Early diagnosis and treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin can significantly reduce complications.

Causes

The exact cause of Kawasaki disease remains unknown. It is suspected to result from an abnormal immune response in genetically predisposed individuals. Environmental factors such as infectious agents, including bacteria or viruses, are considered potential triggers. Epidemiological studies indicate seasonal variations and geographic clustering, supporting an environmental contribution. Genetic studies have implicated genes like ITPKC and CD40, which regulate immune pathways. These findings suggest a multifactorial etiology involving genetic, immunological, and environmental interactions (Burns et al., 2016).

Signs and Symptoms

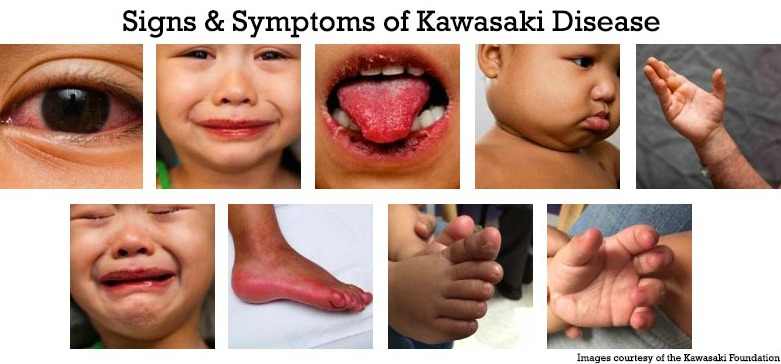

Kawasaki disease typically presents in two phases. The acute phase includes fever persisting for five days or more, accompanied by clinical features like bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis, a polymorphous rash, and erythema of the lips and tongue (strawberry tongue). Swelling and redness in the hands and feet, along with cervical lymphadenopathy, are common. In the subacute phase, peeling of the skin on the hands and feet may occur, and coronary artery abnormalities can develop. Gastrointestinal, neurological, and respiratory symptoms may also appear (Newburger et al., 2016).

Etiology

The etiology of Kawasaki disease remains elusive. However, its geographic prevalence and epidemiological data suggest a link to infectious agents. Studies have found elevated cytokine levels and immune complex deposits in affected tissues, pointing to immune dysregulation. Genetic susceptibility plays a significant role, with HLA class II alleles associated with increased risk. Additionally, polymorphisms in immune-related genes such as IL-10 and FCGR2A have been identified in affected populations (Onouchi et al., 2015). Further research is ongoing to clarify these interactions.

Pathophysiology

Kawasaki disease involves systemic vasculitis affecting medium-sized arteries, particularly the coronary arteries. Immune activation triggers endothelial cell damage, leading to inflammation, leukocyte infiltration, and intimal thickening. Over time, this can result in vascular wall weakening and aneurysm formation. Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) play a pivotal role. This inflammatory cascade can extend beyond the vasculature, affecting organs like the heart, causing myocarditis, and pericarditis (Rowley et al., 2018).

Diagnosis

Kawasaki disease is diagnosed clinically based on criteria established by the American Heart Association (AHA). These include a fever lasting five or more days and at least four of the following: conjunctivitis, oral changes, extremity changes, rash, or lymphadenopathy. Echocardiography is crucial for assessing coronary artery involvement. Laboratory tests may reveal elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), along with thrombocytosis and leukocytosis (McCrindle et al., 2017). Atypical cases may require additional imaging to confirm diagnosis.

Treatment Regimens

Early treatment is essential to prevent coronary complications. The standard regimen includes high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) administered within the first 10 days of illness. Aspirin is used initially in high doses to control inflammation and later in low doses to prevent thrombosis. In refractory cases, corticosteroids or biologic agents like infliximab may be required. Long-term management involves monitoring for coronary artery abnormalities with echocardiography and stress testing, especially in patients with persistent aneurysms (Newburger et al., 2016).

Patient Education

Parents and caregivers should understand the importance of early recognition and treatment to prevent complications. Education should focus on recognizing symptoms like prolonged fever, rash, and swollen extremities. Families must adhere to follow-up care, including regular echocardiograms to monitor coronary health. Awareness of medication adherence and potential side effects, especially during prolonged aspirin use, is essential. Lifestyle modifications, such as heart-healthy diets and physical activity, are crucial for children with residual coronary artery abnormalities (McCrindle et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Kawasaki disease, although rare, is a significant pediatric condition that can cause lifelong cardiovascular complications if untreated. While the exact cause is unknown, genetic predisposition and environmental triggers likely contribute to its development. Early recognition and treatment with IVIG and aspirin remain the cornerstone of management. Long-term follow-up is vital for monitoring cardiac health and ensuring a good quality of life for affected children.

References

Burns, J. C., & Glodé, M. P. (2016). Kawasaki disease. The Lancet, 387(10025), 1731–1742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)33030-0

McCrindle, B. W., Rowley, A. H., & Newburger, J. W. (2017). Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease. Circulation, 135(17), e927-e999. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

Newburger, J. W., Takahashi, M., & Gerber, M. A. (2016). Diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics, 128(4), e1007-e1035. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2051

Onouchi, Y., & Nakagawa, N. (2015). Genetics of Kawasaki disease: Susceptibility and etiology. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 3(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2015.00111

Rowley, A. H., & Shulman, S. T. (2018). Pathogenesis and management of Kawasaki disease. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 30(1), 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000471