Nursing Paper Example on Ichthyosis

Nursing Paper Example on Ichthyosis

Ichthyosis refers to a group of skin disorders characterized by dry, thickened, and scaly skin. The condition can range from mild to severe, with varying degrees of impact on the patient’s quality of life. There are several forms of ichthyosis, including inherited types, which can manifest from birth, and acquired types, which develop later in life. The severity of symptoms varies widely, and treatment is focused on managing symptoms and improving skin appearance.

Causes

Ichthyosis is primarily caused by genetic mutations that affect the skin’s ability to retain moisture and regulate cell turnover. Inherited forms of ichthyosis are typically caused by mutations in specific genes, such as the keratin 1 and keratin 10 genes in ichthyosis vulgaris. These mutations lead to abnormal keratin production, which causes the skin cells to pile up, forming scales. Environmental triggers can also contribute to the condition, although the primary cause is genetic.

In some acquired forms, factors such as infections, metabolic disorders, and other systemic diseases may play a role. Inherited ichthyosis is often passed down in an autosomal dominant or recessive manner, depending on the specific form.

Signs and Symptoms

The most prominent symptom of ichthyosis is the presence of thickened, scaly skin that may cover large areas of the body. The scales can range from fine, powdery flakes to large, thick plaques that are often dry and cracked. Common sites of involvement include the limbs, torso, and scalp, although the condition can affect any part of the body. The severity of scaling varies and can worsen in cold weather or with dry skin conditions. In some forms of ichthyosis, the skin may be red, inflamed, or painful, especially during flare-ups.

Other symptoms may include itching, increased sensitivity to temperature changes, and skin fissures that can lead to secondary infections.

Etiology

Ichthyosis is caused by mutations in genes responsible for skin cell function. For example, ichthyosis vulgaris, the most common form, results from a mutation in the filaggrin gene. This protein is important for maintaining the skin’s barrier function, and its absence or dysfunction leads to skin dryness and scaling. X-linked recessive ichthyosis is another inherited form caused by mutations in the steroid sulfatase gene, which leads to a buildup of certain substances that impair skin turnover.

Other rarer forms of ichthyosis are caused by defects in proteins responsible for skin development or lipid metabolism. Acquired ichthyosis, while less common, can be associated with systemic conditions such as HIV, cancer, hypothyroidism, and sarcoidosis, all of which may lead to abnormal skin changes resembling ichthyosis.

Pathophysiology

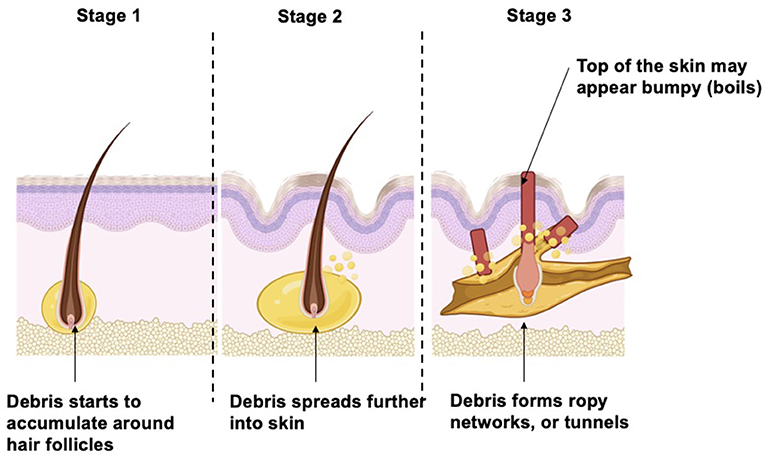

The pathophysiology of ichthyosis involves a disruption in the normal processes of skin cell production, differentiation, and desquamation. In healthy skin, the stratum corneum, the outermost layer, is composed of dead skin cells that are continuously shed and replaced. In individuals with ichthyosis, abnormal keratinization leads to the accumulation of thickened skin cells, resulting in the formation of scales.

The defective genes responsible for ichthyosis disrupt the structure and function of the skin’s outer layer, impairing its ability to retain moisture and protect against environmental stressors. As a result, the skin becomes dry, rough, and prone to cracking. In some forms of ichthyosis, there may be an overproduction of lipids or altered lipid composition in the skin, further contributing to the formation of scales. This process not only affects the appearance of the skin but also its ability to function as a barrier, leaving individuals more vulnerable to infections and other complications.

DSM-5 Diagnosis

There is no specific diagnostic category for ichthyosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) since it is a dermatological condition rather than a psychiatric one. Diagnosis is based on clinical evaluation, including a thorough patient history and physical examination. In most cases, the characteristic appearance of the skin lesions is enough for diagnosis, although genetic testing can confirm the specific form of ichthyosis. In some cases, a skin biopsy may be performed to assess the thickness and composition of the skin layers.

Family history is also an important factor, as many forms of ichthyosis are inherited in an autosomal dominant or recessive pattern. Genetic counseling may be recommended for families affected by hereditary forms of ichthyosis to understand the inheritance pattern and potential risks for future generations.

Treatment Regimens

Management of ichthyosis focuses on alleviating symptoms and preventing complications, as there is currently no cure for the condition. Topical treatments, such as moisturizers, emollients, and keratolytics (e.g., urea, salicylic acid), are commonly used to hydrate the skin and reduce scaling. For more severe cases, prescription-strength creams containing tretinoin or corticosteroids may be used to help normalize skin cell turnover and reduce inflammation.

Oral retinoids such as acitretin may be prescribed for more widespread or severe cases, particularly in conditions like lamellar ichthyosis. In cases where ichthyosis is associated with an underlying systemic condition, treating the primary disease may help improve the skin symptoms.

It is also essential for patients to avoid triggers such as harsh soaps, hot water, and environmental irritants that can worsen dryness and scaling. Regular bathing with lukewarm water and the use of soap substitutes are often recommended to help maintain skin hydration.

Patient Education

Educating patients with ichthyosis about proper skin care is critical to managing the condition effectively. Regular moisturizing is essential, as it helps prevent the skin from becoming dry and cracked. Patients should be advised to apply moisturizers immediately after bathing to lock in moisture. Gentle skin care products, including non-soap cleansers and lukewarm water, should be used to avoid further irritation.

In addition, patients should avoid tight clothing and friction in areas where scaling is prominent, as this can worsen the condition. Sunscreen should be applied regularly to protect the skin from UV damage, as patients with ichthyosis may have increased sensitivity to the sun. Genetic counseling is recommended for patients with hereditary forms of ichthyosis to help them understand the potential risks for family members. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist is important to monitor disease progression and adjust treatment as needed.

Conclusion

Ichthyosis is a group of skin disorders characterized by dry, scaly skin due to defective skin cell production and differentiation. While the condition is often genetic in origin, environmental factors and systemic conditions can also contribute to the disease. Treatment focuses on symptom management, including moisturizing, keratolytics, and oral retinoids for severe cases. Patient education plays a key role in managing the condition, with advice on skin care, avoiding triggers, and protecting the skin from environmental damage. Despite the chronic nature of the disease, early intervention and appropriate treatment can significantly improve the quality of life for individuals affected by ichthyosis.

References

Tobin, D. J., & Gawkrodger, D. J. (2020). Ichthyosis: Clinical presentation and management. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 21(3), 347-357. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40257-020-00507-2

Zouboulis, C. C., & Bechara, F. G. (2021). Ichthyosis: Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Dermatologic Clinics, 39(2), 167-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2020.11.007

Bialynicki-Birula, R., & Wróblewska, A. (2020). The genetics of ichthyosis: Pathogenesis and clinical presentation. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 34(5), 1015-1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16456