Impact of health literacy

Impact of health literacy

(Impact of health literacy) What is an impact of health literacy on health outcome?

The Impact of Health Literacy on Health Outcomes

Health literacy significantly impacts health outcomes. It encompasses a person’s ability to obtain, understand, and use health information to make informed decisions. This ability is crucial for managing health, navigating the healthcare system, and engaging in health-promoting behaviors. Consequently, higher health literacy levels lead to better health outcomes, while low health literacy can result in poorer health and increased healthcare costs.

Understanding Health Information

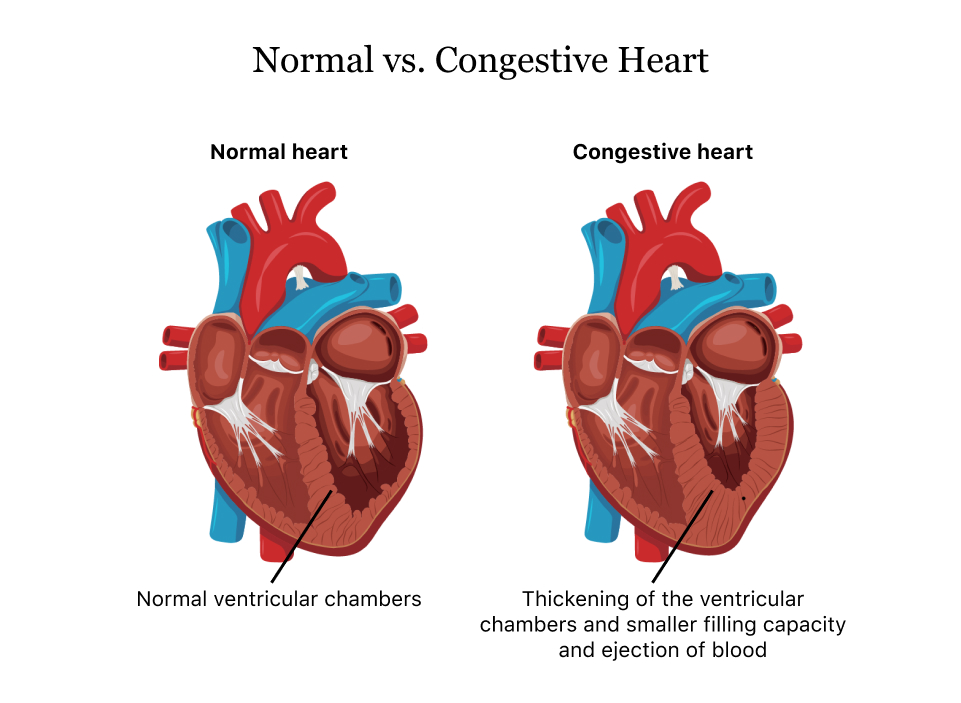

Firstly, health literacy enables individuals to comprehend health information accurately. People with high health literacy can read and understand prescription labels, appointment slips, medical instructions, and educational brochures. This understanding allows them to follow treatment plans correctly, take medications as prescribed, and adhere to recommended health behaviors. For instance, a patient with diabetes must understand how to monitor blood sugar levels, recognize symptoms of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, and know when to seek medical help. This knowledge directly impacts their ability to manage their condition and avoid complications. (Impact of health literacy)

Navigating the Healthcare System

Additionally, health literacy affects an individual’s ability to navigate the healthcare system effectively. Individuals with high health literacy can find and use healthcare services appropriately. They know how to schedule appointments, communicate effectively with healthcare providers, and understand their rights and responsibilities within the healthcare system. This proficiency helps them access preventive services, manage chronic conditions, and receive timely medical care. For example, a person who understands the importance of regular screenings for hypertension or cancer is more likely to utilize these services, leading to early detection and better health outcomes.

Engaging in Health-Promoting Behaviors

Health literacy also plays a critical role in promoting healthy behaviors. Individuals with high health literacy are more likely to engage in preventive health behaviors, such as exercising regularly, eating a balanced diet, and avoiding harmful substances like tobacco and excessive alcohol. They are also more likely to understand and act on public health messages, such as the importance of vaccinations or the need for social distancing during a pandemic. These behaviors contribute to overall better health and reduced risk of chronic diseases.

Low Health Literacy and Health Disparities

Conversely, low health literacy can lead to significant health disparities. Individuals with low health literacy often struggle to understand health information, follow medical instructions, and navigate the healthcare system. This struggle can result in mismanagement of chronic diseases, increased hospitalizations, and higher healthcare costs. For example, a patient with low health literacy might misunderstand medication instructions, leading to improper use and subsequent health complications. Moreover, these individuals may avoid seeking medical care due to confusion or fear, resulting in delayed diagnoses and treatments. (Impact of health literacy)

Impact on Health Outcomes

Research consistently shows that low health literacy is associated with poorer health outcomes. Patients with low health literacy often have higher rates of hospitalizations, more frequent use of emergency services, and poorer disease management. For instance, a study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that patients with low health literacy were more likely to have poor control of chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. They also had higher rates of complications and hospital readmissions.

Improving Health Literacy

Improving health literacy is essential for enhancing health outcomes. Healthcare providers play a crucial role in this process. They can use plain language, provide clear and concise instructions, and use teach-back methods to ensure patients understand their care plans. Additionally, healthcare systems can develop and distribute easy-to-read health materials and utilize technology, such as apps and online resources, to support patient education. Policymakers can also promote health literacy by integrating it into public health initiatives and educational curricula.

Conclusion

Health literacy is a critical determinant of health outcomes. High health literacy enables individuals to understand health information, navigate the healthcare system, and engage in health-promoting behaviors, leading to better health outcomes. Conversely, low health literacy is associated with poorer health outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Efforts to improve health literacy can significantly enhance public health and reduce health disparities. By prioritizing health literacy, healthcare providers, systems, and policymakers can contribute to a healthier, more informed population. (Impact of health literacy)

References

Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., & Crotty, K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 97-107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

Nutbeam, D. (2008). The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2072-2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050

Brach, C., & Harris, L. M. (2021). Health literacy research and practice: Addressing health disparities and enhancing health outcomes. Health Affairs, 40(2), 203-211. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01436

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/article_7866255_foods-you-should-eat-every-week-to-lose-weight_-04-d58e9c481bce4a29b47295baade4072d.jpg)