Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) stands as a perplexing neurological ailment, disrupting neuromuscular communication and inducing muscle weakness. This chronic condition poses significant challenges to those affected, impacting their daily activities and overall quality of life. Despite its prevalence, MG remains enigmatic in terms of its precise etiology and optimal management strategies. Understanding this disorder is essential, not only for healthcare professionals but also for patients and their caregivers, to navigate its complexities effectively. In this essay, we delve into the intricacies of Myasthenia Gravis, exploring its causes, signs and symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, DSM-5 diagnosis, treatment regimens, and the crucial aspect of patient education. By comprehensively examining each aspect, we aim to shed light on this condition, offering insights into its management and fostering a better understanding among those affected and the broader community. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

Causes

The exact cause of Myasthenia Gravis (MG) remains elusive, but it is primarily attributed to autoimmune dysfunction. In MG, the immune system mistakenly targets the acetylcholine receptors at neuromuscular junctions, disrupting the transmission of signals between nerves and muscles. This autoimmune response leads to the production of antibodies that either block or destroy these receptors, impairing their function.

Several factors may contribute to the development of MG. Genetic predisposition plays a role, as individuals with a family history of autoimmune disorders are more susceptible. Additionally, environmental factors such as infections, particularly respiratory or viral illnesses, can trigger the onset or exacerbation of MG symptoms.

Furthermore, certain medications, such as antibiotics, quinidine, and beta-blockers, have been associated with the development of MG or worsening of symptoms in individuals predisposed to the disorder. Moreover, hormonal changes, such as those occurring during pregnancy or menstrual cycles, may influence MG symptoms.

Thymus gland abnormalities are also linked to MG, with around 15% of individuals with MG having a thymoma (tumor of the thymus gland), and a higher percentage showing thymic hyperplasia (enlargement of the thymus gland). The thymus gland plays a role in the development and maturation of certain immune cells, and its abnormalities are thought to contribute to the autoimmune response seen in MG.

While these factors are associated with the development or exacerbation of MG, the precise interplay between genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and immune system dysfunction remains the subject of ongoing research. Understanding the underlying causes of MG is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic approaches and improving outcomes for individuals affected by this debilitating neurological disorder. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

Signs and Symptoms

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) manifests through a variety of signs and symptoms, primarily stemming from muscle weakness and fatigue. These symptoms can vary widely among individuals and may fluctuate in severity over time.

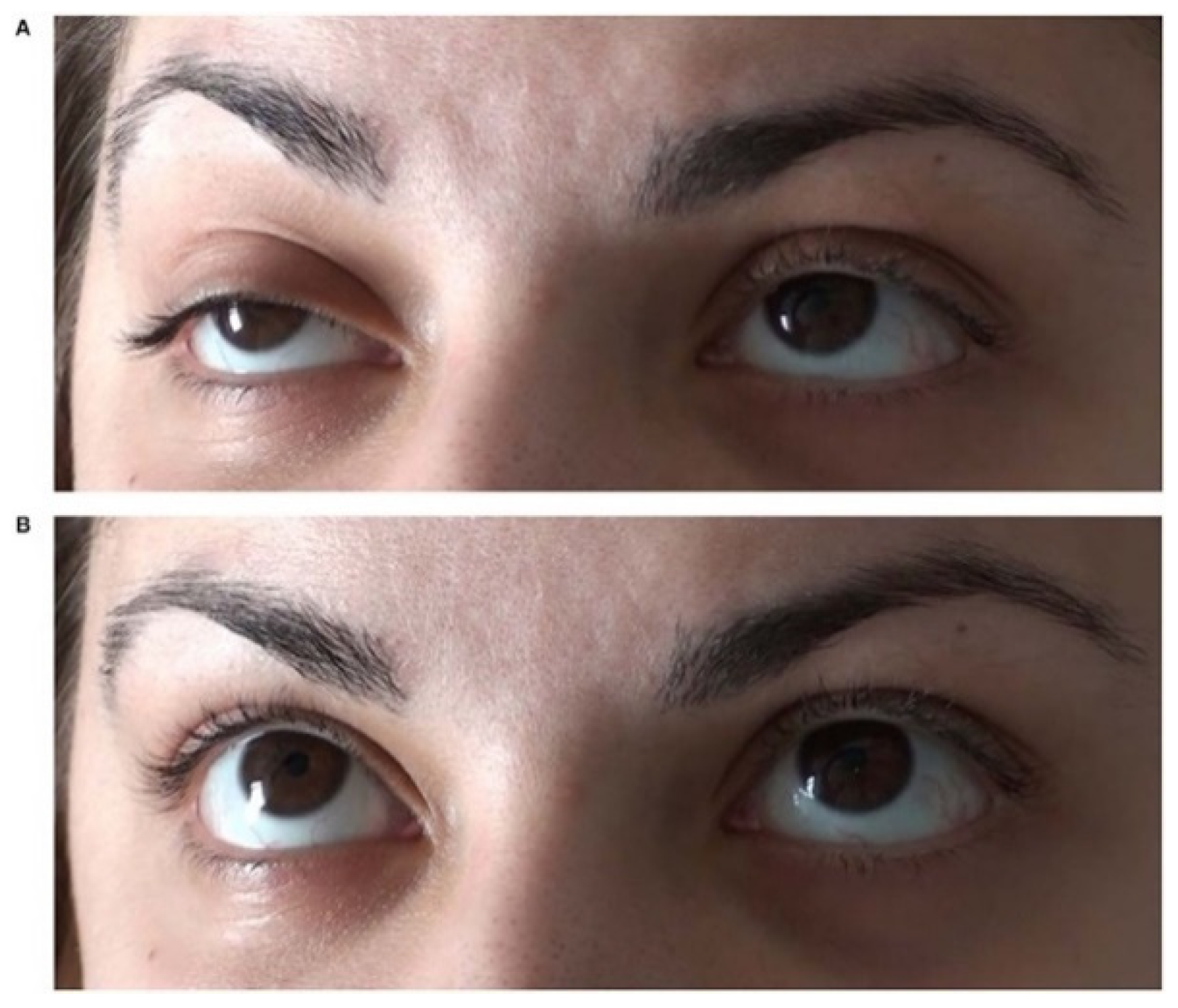

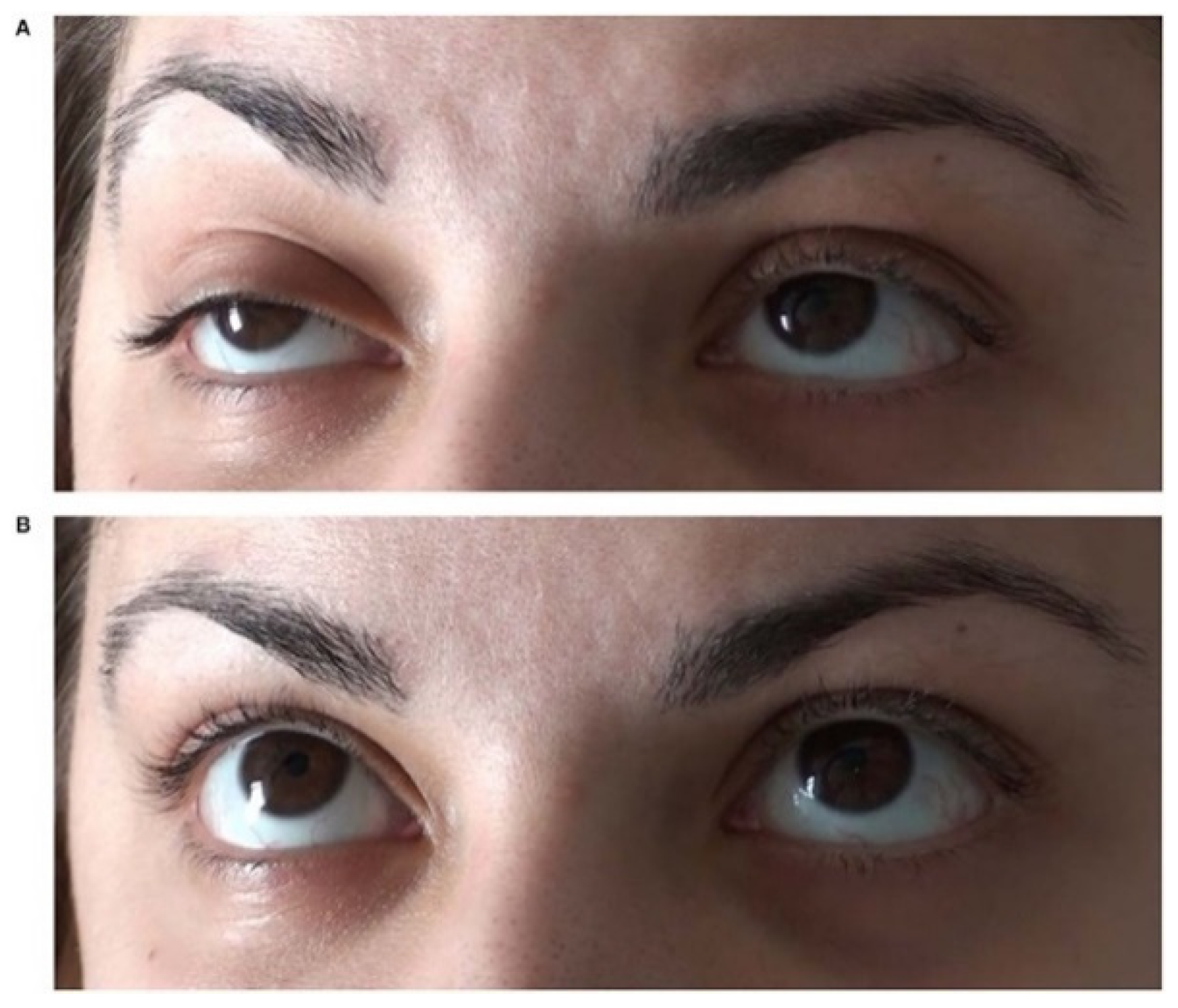

One of the hallmark symptoms of MG is muscle weakness, which typically worsens with activity and improves with rest. This weakness commonly affects muscles that control eye movements and eyelid function, leading to drooping eyelids (ptosis) and double vision (diplopia). Ptosis can impair vision and cause discomfort, while diplopia can significantly impact daily activities such as reading and driving.

Additionally, individuals with MG may experience weakness in other facial muscles, leading to difficulty in facial expressions, chewing, and swallowing. Weakness in the muscles of the throat and neck can result in dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and dysarthria (difficulty speaking), which can affect nutrition and communication.

Muscle weakness in MG is not limited to the face and neck but can also affect the limbs, leading to difficulty in activities such as lifting objects, climbing stairs, or walking long distances. The weakness tends to be more pronounced after repetitive use of muscles and may improve with rest.

Fatigue is another common symptom of MG, often accompanying muscle weakness. This fatigue can be both physical and mental, impacting activities that require sustained effort or concentration.

In some cases, MG can also affect respiratory muscles, leading to respiratory distress, shortness of breath, or difficulty breathing, particularly during physical exertion or at night.

Overall, the signs and symptoms of MG can significantly impair daily functioning and quality of life. Prompt recognition and management of these symptoms are crucial for improving outcomes and enhancing the well-being of individuals living with this condition. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

Etiology

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is primarily characterized by autoimmune dysfunction, where the body’s immune system erroneously targets components of the neuromuscular junction, leading to muscle weakness. The exact etiology of MG remains elusive, but several factors contribute to its development and progression.

Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in the etiology of MG, as individuals with a family history of autoimmune disorders are more susceptible to developing the condition. Certain genetic variations may predispose individuals to an abnormal immune response against the neuromuscular junction components, increasing their risk of MG.

Environmental factors also contribute to the etiology of MG. Infections, particularly respiratory or viral illnesses, have been implicated as potential triggers for the onset or exacerbation of MG symptoms. These infections can stimulate the immune system and precipitate an autoimmune response against the neuromuscular junction.

Furthermore, certain medications have been associated with the development or worsening of MG symptoms. Antibiotics, quinidine, and beta-blockers are among the medications that can exacerbate MG or trigger its onset, especially in individuals predisposed to the disorder.

Thymus gland abnormalities are also linked to the etiology of MG. Approximately 15% of individuals with MG have a thymoma (tumor of the thymus gland), while a higher percentage exhibit thymic hyperplasia (enlargement of the thymus gland). The thymus gland plays a crucial role in the maturation of immune cells, and abnormalities in this gland are thought to contribute to the autoimmune response seen in MG.

Overall, the etiology of MG is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay between genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and immune system dysfunction. Understanding these factors is essential for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of MG and developing targeted therapeutic approaches to improve outcomes for affected individuals. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

Pathophysiology

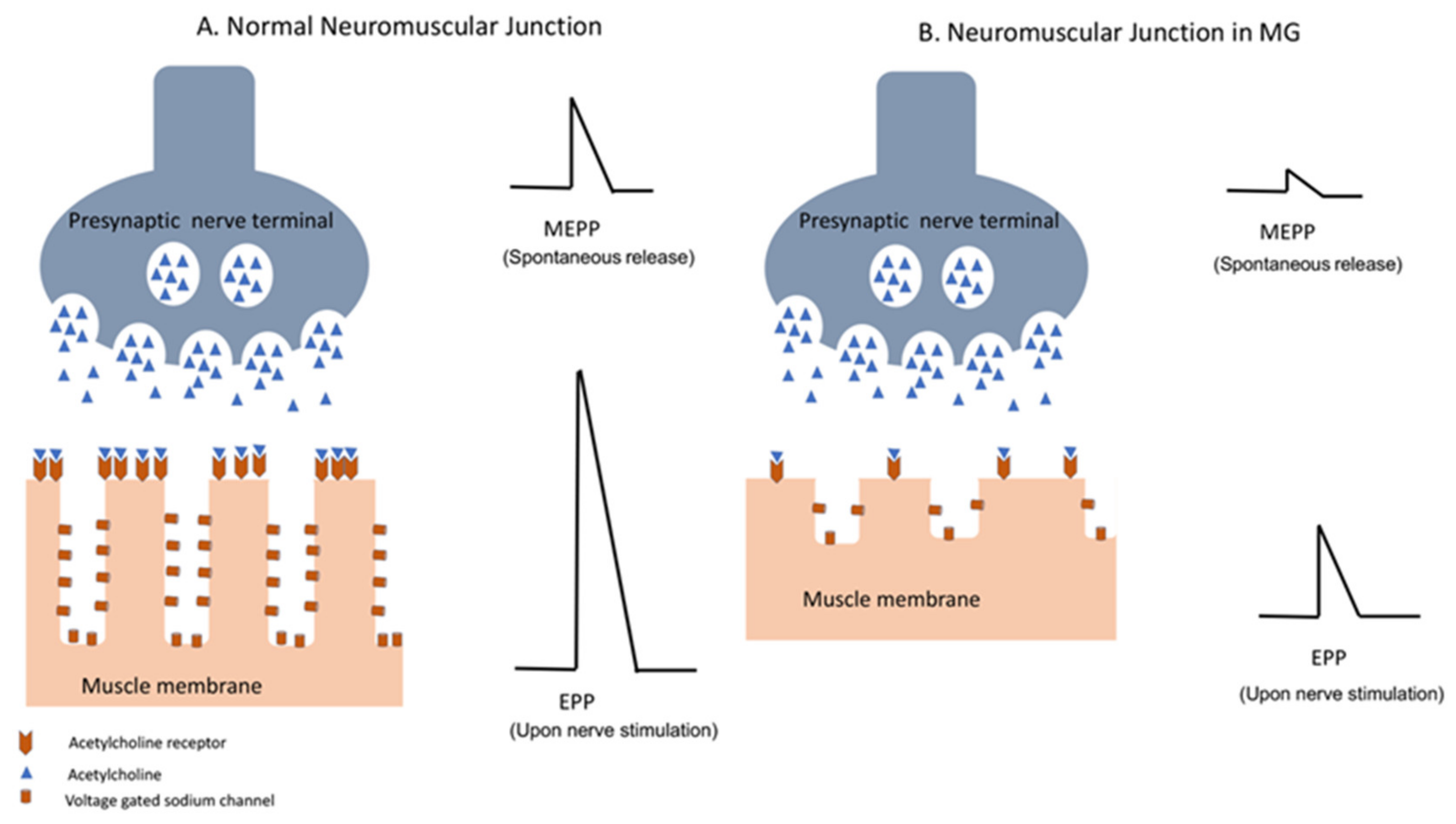

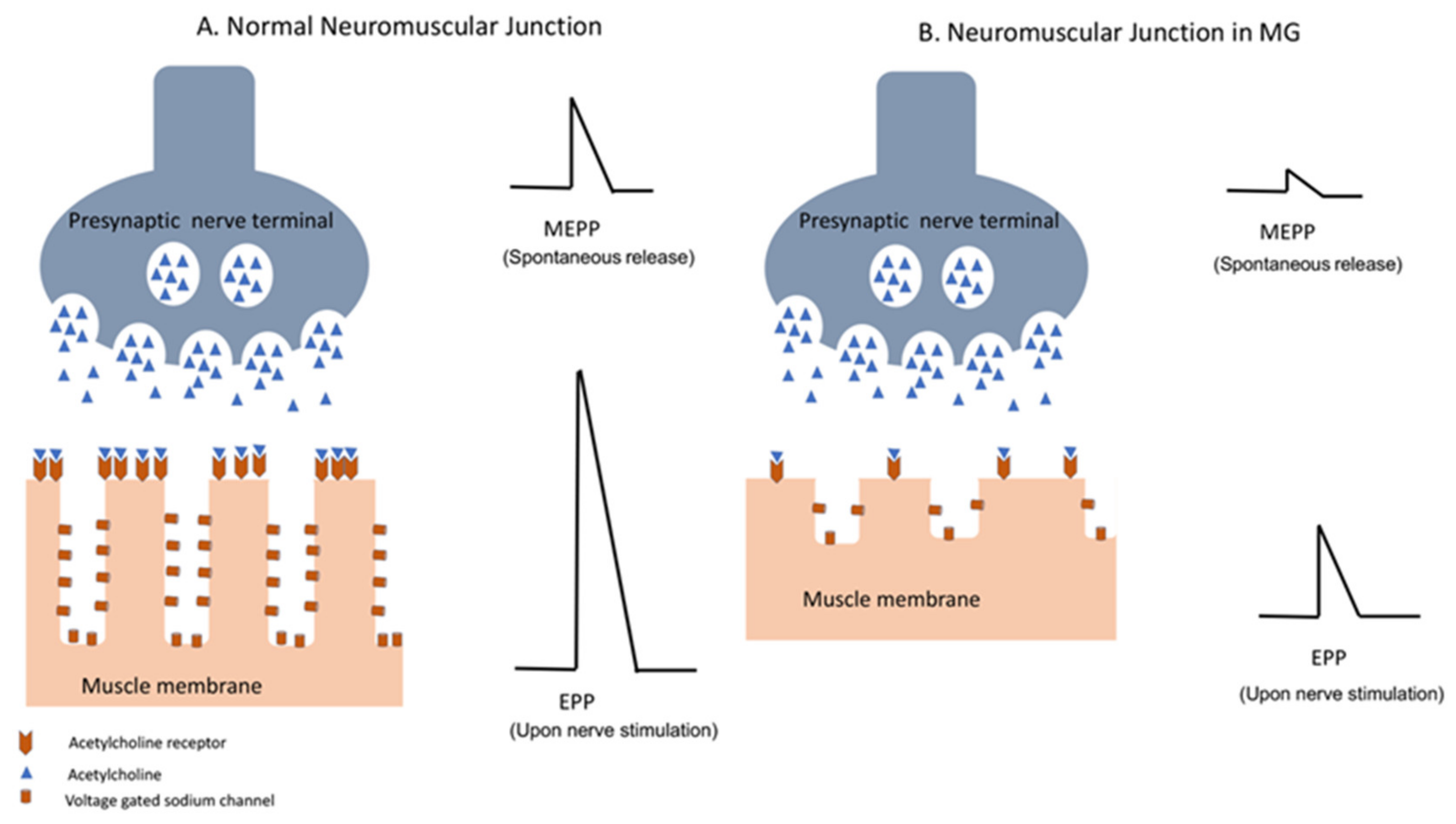

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) arises from a disruption in neuromuscular transmission due to autoimmune dysfunction. The pathophysiology of MG involves an intricate interplay of immune-mediated processes that target the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), impairing communication between nerves and muscles.

In MG, the immune system produces autoantibodies, primarily immunoglobulin G (IgG), that target key components of the NMJ, particularly the acetylcholine receptors (AChR). These autoantibodies bind to AChR, leading to receptor blockade or destruction through complement-mediated mechanisms. Consequently, the binding of acetylcholine (ACh) to its receptors on the postsynaptic membrane is inhibited, disrupting the transmission of nerve impulses across the NMJ.

Additionally, some individuals with MG produce autoantibodies against muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), another protein crucial for NMJ function. These MuSK autoantibodies interfere with signaling pathways involved in AChR clustering and maintenance, further exacerbating neuromuscular dysfunction.

The resulting reduction in AChR density and impaired AChR function at the NMJ leads to muscle weakness and fatigue, characteristic of MG. The severity of symptoms correlates with the extent of AChR loss and dysfunction, as well as the degree of NMJ remodeling.

Furthermore, the thymus gland plays a significant role in the pathophysiology of MG, particularly in individuals with thymoma or thymic hyperplasia. Abnormalities in the thymus gland, such as follicular hyperplasia or germinal center formation, contribute to the breakdown of self-tolerance and the generation of autoreactive T cells, perpetuating the autoimmune response against the NMJ.

Overall, the pathophysiology of MG involves a complex cascade of immune-mediated events that disrupt neuromuscular transmission, resulting in muscle weakness and fatigue. Understanding these underlying mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted therapies to alleviate symptoms and improve outcomes for individuals with MG. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

DSM-5 Diagnosis

Diagnosing Myasthenia Gravis (MG) involves a comprehensive evaluation based on clinical presentation, electromyography (EMG), serological tests, and imaging studies. While the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), primarily focuses on mental health conditions, the diagnosis of MG typically follows guidelines established by medical associations and neurology societies.

Clinical assessment is fundamental in diagnosing MG, with emphasis on characteristic symptoms such as muscle weakness, ptosis, diplopia, dysphagia, and dysarthria. The fluctuating nature of symptoms and their exacerbation with activity aid in distinguishing MG from other neuromuscular disorders.

Electromyography (EMG) plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of MG by assessing neuromuscular transmission. EMG findings typically reveal a decremental response to repetitive nerve stimulation, reflecting impaired neuromuscular transmission characteristic of MG.

Serological tests are utilized to detect autoantibodies against acetylcholine receptors (AChR) or muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), which are present in the majority of individuals with MG. A positive serological result, in conjunction with clinical findings, further supports the diagnosis of MG.

Imaging studies, particularly computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, are performed to assess the thymus gland in individuals suspected of having thymoma or thymic hyperplasia associated with MG.

Overall, the diagnosis of MG is based on a combination of clinical features, electromyography findings, serological tests for autoantibodies, and imaging studies to evaluate thymic abnormalities. A comprehensive diagnostic approach ensures accurate identification of MG, enabling timely initiation of appropriate management strategies to optimize patient outcomes. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

Treatment Regimens and Patient Education

Management of Myasthenia Gravis (MG) involves a multifaceted approach aimed at alleviating symptoms, improving neuromuscular transmission, and suppressing the autoimmune response. Additionally, patient education plays a crucial role in empowering individuals with MG to actively participate in their care and optimize treatment outcomes.

Treatment Regimens:

- Medications: Pharmacotherapy is the cornerstone of MG management. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as pyridostigmine improve neuromuscular transmission by inhibiting the breakdown of acetylcholine. These medications help alleviate muscle weakness and fatigue in many individuals with MG.

- Immunosuppressants: For individuals with moderate to severe MG or those who do not respond adequately to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or rituximab may be prescribed. These medications help suppress the autoimmune response, thereby reducing the production of autoantibodies and mitigating disease progression.

- Plasmapheresis and Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIg): In acute exacerbations of MG or when rapid symptom relief is needed, plasmapheresis or IVIg therapy may be employed to remove circulating autoantibodies and modulate immune function, respectively.

- Thymectomy: Surgical removal of the thymus gland (thymectomy) is recommended for individuals with thymoma or thymic hyperplasia associated with MG. Thymectomy may result in disease remission or reduction in disease severity, particularly in younger individuals with early-stage MG.

- Symptomatic Management: Adjunctive therapies such as ocular lubricants for dry eyes, speech therapy for dysarthria, and dietary modifications for dysphagia may be recommended to address specific symptoms and improve quality of life.

Patient Education:

- Medication Adherence: Patients must understand the importance of adhering to their prescribed medication regimen, including dosing schedules and potential side effects.

- Recognition of Exacerbations: Educating patients about the signs and symptoms of MG exacerbations, such as worsening muscle weakness or respiratory distress, enables prompt medical intervention and prevents complications.

- Avoidance of Triggers: Patients should be advised to avoid factors known to exacerbate MG symptoms, such as stress, fatigue, certain medications, and infections.

- Regular Follow-up: Encouraging patients to attend regular follow-up appointments with their healthcare providers ensures ongoing monitoring of disease progression and treatment efficacy.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Providing guidance on energy conservation strategies, adaptive devices, and support services helps individuals with MG optimize their daily activities and maintain independence.

By employing a comprehensive treatment approach and empowering patients with education and support, the management of Myasthenia Gravis can be tailored to individual needs, leading to improved symptom control and enhanced quality of life. (Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

Conclusion

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) presents a complex clinical challenge, characterized by muscle weakness and fatigue due to autoimmune dysfunction at the neuromuscular junction. In this essay, we explored the multifaceted aspects of MG, including its causes, signs and symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, DSM-5 diagnosis, treatment regimens, and patient education. By employing a concise yet comprehensive approach, we elucidated the intricate interplay of immune-mediated processes underlying MG and highlighted the importance of accurate diagnosis and tailored treatment strategies. Furthermore, the inclusion of patient education as a pivotal component of MG management emphasizes the significance of empowering individuals with knowledge and support to actively participate in their care. Overall, by understanding the complexities of MG and implementing a holistic approach encompassing both medical interventions and patient education, healthcare providers can optimize outcomes and enhance the quality of life for individuals living with this challenging neurological disorder.(Nursing Paper Example on Myasthenia Gravis: Understanding a Neurological Disorder)

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559331/

Do you need a similar assignment done for you from scratch? Order now!

Use Discount Code "Newclient" for a 15% Discount!