Nursing Paper Example on SJS

Nursing Paper Example on SJS

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a rare but life-threatening disorder characterized by severe reactions affecting the skin and mucous membranes. It typically involves an adverse response to medications or, in rarer cases, infections. SJS is considered a medical emergency due to its potential for rapid progression and high risk of complications.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Underlying Causes

The main trigger for Stevens–Johnson syndrome is adverse reactions to medications, including antibiotics, anticonvulsants, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and sulfonamides. These drugs can initiate a hypersensitivity reaction in genetically predisposed individuals, leading to an inflammatory response in the skin and mucous membranes (Guegan & Bastuji-Garin, 2017). In some cases, SJS is linked to viral or bacterial infections, such as herpes simplex virus, mycoplasma pneumoniae, or hepatitis (Schwartz et al., 2013).

Mechanism of Disease Development

The pathophysiology of SJS involves a cell-mediated immune response, where the body misidentifies certain drugs or infections as harmful and launches an inflammatory attack. This reaction leads to widespread apoptosis, or programmed cell death, within the skin and mucosal tissues. The activation of cytotoxic T-cells and natural killer cells is thought to be responsible for this cellular destruction, causing detachment of the epidermis and subsequent blistering and erosions (Roujeau & Stern, 1994).

Signs and Symptoms

Initial Presentation

Early symptoms of SJS are often nonspecific and include fever, sore throat, headache, cough, and malaise. These prodromal symptoms typically last 1–3 days and are followed by the characteristic skin and mucosal lesions.

Skin and Mucous Membrane Lesions

The hallmark symptom of SJS is the rapid onset of red or purplish skin lesions that spread and merge, forming large areas of necrotic tissue. The lesions commonly start on the face and trunk, later extending to other body parts. Blistering, followed by detachment of the epidermis, gives the skin a scalded appearance. Lesions also affect mucous membranes, including the mouth, eyes, and genital areas, leading to painful ulcers and erosions (Schwartz et al., 2013).

Complications and Prognosis

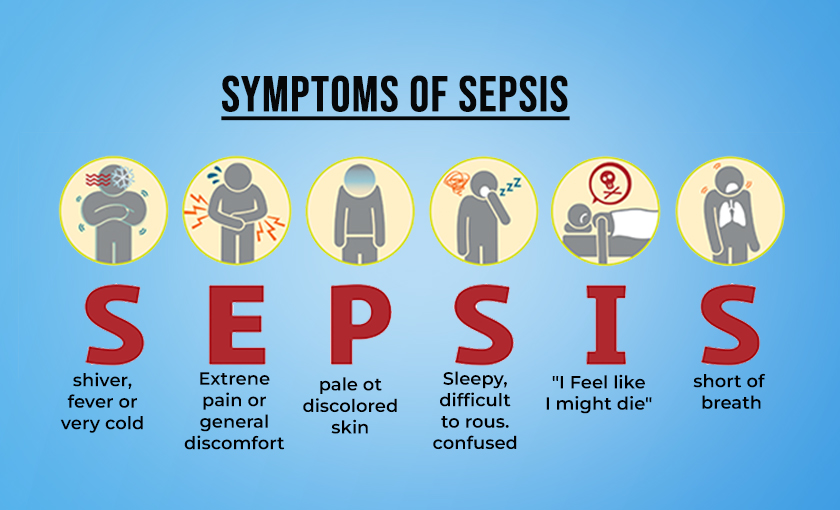

The loss of skin integrity in SJS increases the risk of infection, dehydration, and sepsis. Eye involvement may lead to conjunctivitis, corneal ulceration, and, in severe cases, blindness. Respiratory involvement may also occur, contributing to respiratory failure. Mortality rates vary depending on the extent of skin detachment and the patient’s overall health, but they range from 10% to 30% (Mockenhaupt et al., 2008).

(Nursing Paper Example on SJS)

Risk Factors

Genetic Predisposition

Specific genetic markers, such as the HLA-B*1502 allele in Southeast Asian populations, are linked to a higher risk of developing SJS, particularly in response to certain drugs like carbamazepine. Genetic testing is recommended in at-risk populations before prescribing medications associated with SJS (Sassolas et al., 2010).

Medication Use

Medications are the primary triggers for SJS, with the highest risk during the first 1–3 weeks of initiating a new drug. Common culprits include antiepileptics (such as lamotrigine and phenytoin), allopurinol, antibiotics (such as sulfonamides and penicillins), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Guegan & Bastuji-Garin, 2017).

Infections

Infections, especially in children, are another cause of SJS. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is particularly associated with SJS in pediatric cases. Herpes simplex virus is also a recognized trigger, though less common (Harr & French, 2010).

Diagnosis

Clinical Examination and Patient History

Diagnosis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome is based on the clinical presentation and patient history, especially recent drug exposure or infections. SJS is distinguished from similar skin disorders by the extent of epidermal detachment, which involves less than 10% of the body surface area. A body surface area involvement of 10–30% is classified as overlap syndrome with toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), while more than 30% signifies TEN (Schwartz et al., 2013).

Skin Biopsy

Skin biopsy may be performed to confirm SJS and rule out other conditions. Histological findings show necrosis of keratinocytes and lymphocytic infiltration, characteristic of SJS (Roujeau & Stern, 1994).

(Nursing Paper Example on SJS)

Treatment and Management

Immediate Discontinuation of Causative Agents

The most crucial step in managing SJS is identifying and discontinuing the offending medication as quickly as possible. Timely withdrawal of the drug significantly reduces mortality risk (Schwartz et al., 2013).

Supportive Care

Patients with SJS are typically treated in an intensive care unit or burn unit. Supportive care involves fluid replacement, electrolyte management, wound care, and pain management. Infection prevention is paramount, as patients are vulnerable to secondary infections due to skin barrier loss.

Pharmacologic Interventions

While no specific treatment for SJS exists, some patients may benefit from systemic corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), or cyclosporine to control inflammation. However, evidence supporting these treatments remains limited and is often case-specific (Harr & French, 2010).

Long-Term Management and Follow-Up

Long-term management of SJS survivors includes monitoring for sequelae, particularly in the eyes, skin, and respiratory system. Many patients experience chronic eye problems, scarring, and psychological impacts due to the disease’s severity and disfiguring nature.

Prevention and Patient Education

Drug Avoidance and Screening

Patients who have had SJS should avoid the causative drug and similar medications. Medical records should be flagged to prevent re-prescription of these drugs. Genetic screening may be advisable in certain populations or patients, especially for those requiring drugs known to cause SJS (Sassolas et al., 2010).

Patient and Caregiver Awareness

Educating patients and caregivers on early signs of SJS is vital. Awareness of high-risk medications and symptoms can promote early detection and treatment, potentially reducing severity and complications.

Conclusion

Stevens–Johnson syndrome is a serious, life-threatening condition requiring prompt recognition and intervention. Often triggered by medications, SJS can cause severe skin and mucous membrane damage, posing significant risks to patient health. Management focuses on discontinuing the causative agent and providing supportive care, with pharmacologic treatments as secondary options. Genetic factors play a role in susceptibility, highlighting the importance of tailored treatment and preventative measures in high-risk individuals. Given its rapid progression and high mortality rate, SJS underscores the need for cautious medication use, early diagnosis, and comprehensive care for affected individuals.

(Nursing Paper Example on SJS)

References

Guegan, S., & Bastuji-Garin, S. (2017). Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: Definitions, diagnosis, and treatment. La Presse Médicale, 46(9), 861–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2017.09.015

Harr, T., & French, L. E. (2010). Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Dermatologic Clinics, 28(4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2010.06.011

Mockenhaupt, M., Viboud, C., Dunant, A., Naldi, L., Halevy, S., Bouwes Bavinck, J. N., & Roujeau, J. C. (2008). Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 128(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5701033

Roujeau, J. C., & Stern, R. S. (1994). Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. New England Journal of Medicine, 331(19), 1272–1285. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199411103311906

Sassolas, B., Haddad, C., Mockenhaupt, M., Dunant, A., Liss, Y., Bork, K., & Roujeau, J. C. (2010). ALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Comparison with case-control analysis. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 88(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2010.58

Schwartz, R. A., McDonough, P. H., & Lee, B. W. (2013). Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Part I. Introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 69(2), 173.e1–173.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.003