Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD

Name: S.H.

DOB: November 29th, 2011

Minor: Yes

Age: 11 Years

Gender: Female

Accompanied by: Mother

SUBJECTIVE:

CC: “S.H. is experiencing difficulties in school, has problems paying attention, forgets easily, and cannot stay still.”

HPI: The patient is an 11-year-old female presenting at the clinic with her mother, who claims she is experiencing difficulties in school, problems paying attention, and remembering things. The mother states S.H. cannot stay still as she jumps from one activity to another. She cannot remember her assignments very well and needs an assignment list, which she also fails to keep track of and loses, necessitating the teacher to give her mother another list. She cannot stay still while reading unless she really likes it; then, she can stay still for about five minutes. S.H. has difficulties remembering what she read or what her teacher read her, and she loses her things easily. She loses her temper when her teachers ask her something she did not hear. S.H. states that she daydreams about different things, including good and bad times. She is frustrated when she makes a mistake while doing her assignments because she is trying to do it right. The mother states that the patient’s concentration is impaired but loves art, although she jumps from one painting to another at the museum. The mother reports that S.H. loves video games, and she can stay on them for long periods. The mother reported risky behavior when S.H. was young and a lack of perception of danger. (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD)

Social History: S.H. lives with her parents in Washington, D.C. She has a younger brother.

Substance Current Use and History: Denied any substance use history.

Legal History: None reported.

Family Psychiatric/Substance Use History: Denied family mental health or substance use issues.

Past Psychiatric History:

Hospitalization: Denied previous hospitalization

Medication trials: No previous medical trails

Psychotherapy or Previous Psychiatric Diagnosis: No previous psychiatric diagnosis

Medical History: Denies medical history.

- Current Medications:None reported.

- Allergies:

- Reproductive Hx:

Development Milestones:

Development milestones met on time

Health Promotion:

Vaccination up to date

Sleeps 9-10hrs/night

Has proper nutrition per PCP, although meals are difficult because she cannot stay still to eat.

ROS:

General: Denies weight loss, fever, chills, weakness, or fatigue.

HEENT: Eyes: denies visual loss, blurred vision, double vision, or yellow sclerae. Ears, Nose, Throat: No hearing loss, sneezing, congestion, runny nose, or sore throat.

Skin: No rash or itching.

Cardiovascular: Denies chest pain, chest pressure, or chest discomfort. No palpitations or edema.

Respiratory: Denies wheezes, shortness of breath, consistent coughs, and breathing difficulties while resting.

Gastrointestinal: No anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. No abdominal pain or blood.

Genitourinary: Denies burning on urination, urgency, hesitancy, odor, odd color

Neurological: Denies headache, dizziness, syncope, paralysis, ataxia, numbness, or tingling in the extremities. No change in bowel or bladder control. Reports difficulties concentrating and paying attention. Reports memory difficulties.

Musculoskeletal: Denies muscle, back pain, joint pain, or stiffness.

Hematologic: Denies anemia, bleeding, or bruising.

Lymphatics: Denies enlarged nodes. No history of splenectomy.

Endocrinologic: Sweating, No reports of cold or heat intolerance. No polyuria or polydipsia.

OBJECTIVE:

Vital signs: Stable

Temp: 97.4F

B.P.: 100/80

P: 58

R.R.: 14

O2: Room air

Pain: 0/10

Ht: 4’5 feet

Wt: 65 lbs

BMI: 16.3

BMI Range: Healthy weight

Physical Exam:

General appearance: The patient looks well-fed and in good health. Her conversation and engagement with interviewer is irregular, requiring intervention from the mother to help answer the questions or ask the patient to answer. She drifts from the conversation quickly, not paying full attention to the questions asked. Her attention and concentration are impaired, making inquiry challenging.

HEENT: Normocephalic and atraumatic. Sclera anicteric, No conjunctival erythema, PERRLA, oropharynx red, moist mucous membranes.

Neck: Supple. No JVD. Trachea midline. No pain, swelling or palpable nodules.

Heart/Peripheral Vascular: Regular rate and rhythm noted. No murmurs. No palpitation. No peripheral edema to palpation bilaterally.

Cardiovascular: Although the patient’s heartbeat and rhythm are regular, there are murmurs and other sounds coming from her chest. The patient’s heart rate is constant and capillaries refill in two seconds.

Musculoskeletal: Normal range of motion. Regular muscle mass for age. No signs of swelling or joint deformities.

Respiratory: No wheezes and respirations are easy and regular.

Neurological: Balance is stable, gait is normal, posture is erect, tone is good, but speech is irregular. She has memory problems and cannot remember the questions asked by the interviewer. Her concentration and attention are impaired.

Psychiatric: The patient fast switches from one thing to another and cannot stick to the discussion and the interview, indicating impaired attention and concentration. Patient is easily distracted, yet occasionally appears to pay attention to the interviewer.

Neuropsychological testing: Patient has difficulties executing functions like reading, doing assignments and homework, and eating, where she is required to prioritize, plan, inhibit behavior, and attend to processing speed. (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD)

ASSESSMENT:

Mental Status Examination:

The patient is an 11-year-old female presenting with difficulties in school and attention and memory problems. The patient reports easy irritability and being short-tempered when teachers ask about something she did not hear. During the psychiatric interview, the patient was sometimes uncooperative, and her concentration was impaired, making it difficult to conduct the inquiry, necessitating the mother’s intervention to help answer the questions. However, the patient was polite, making it easy to establish a rapport. She indicated decreased attention and concentration. The patient is forgetful and shows short- and long-term memory issues. Additionally, she is fidgety and cannot stay still throughout an activity. (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD)

Differential Diagnosis:

- 9. Attention-Deficit hyperactivity disorder (Confirmed):

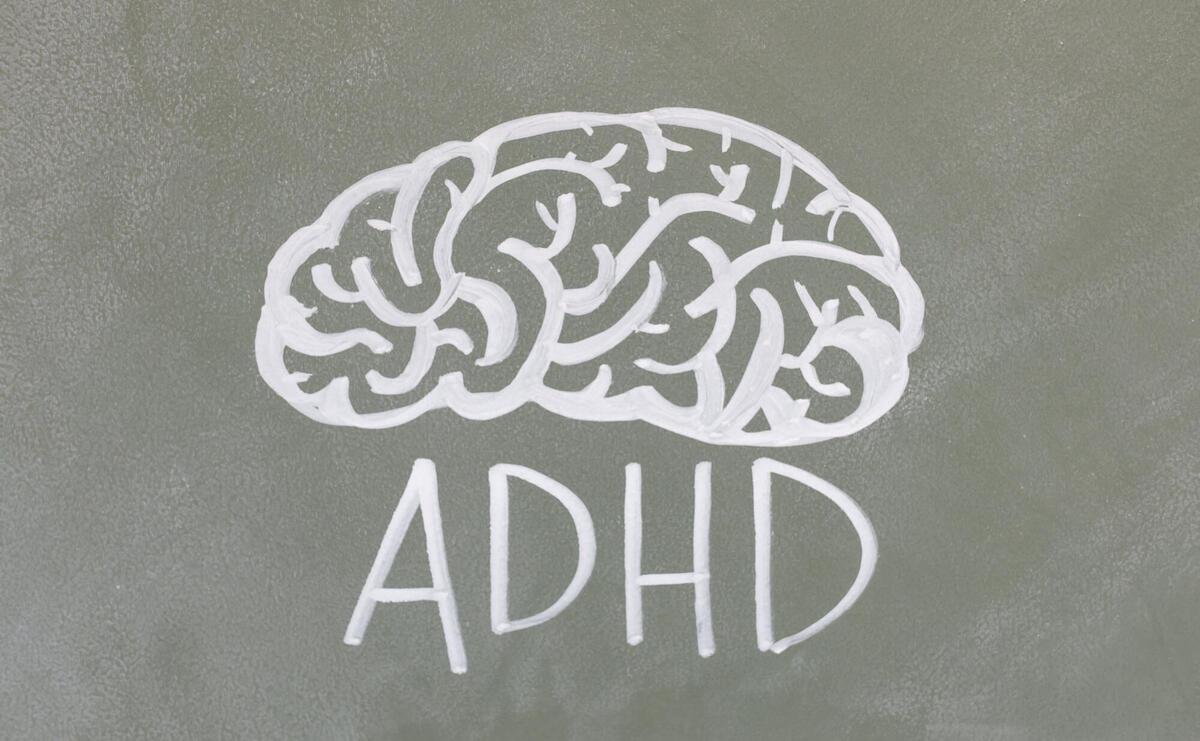

Millions of children are affected with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a long-term mental health problem that often worsens as people get older. Hyperactivity, impulsive conduct, and problems maintaining attention are all persistent symptoms of ADHD. Low self-esteem, problematic relationships, and poor involvement are common problems for people with ADHD, especially children (Magnus et al., 2017). The patient indicated difficulties at school, memory issues, and impaired attention and concentration. The mother noted inattention symptoms since the patient was in kindergarten. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for children with ADHD include a pervasive inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity pattern interfering with functioning or development as indicated by inattention, with six or more symptoms persisting for a minimum of six weeks to a point it is inconsistent with developmental level and negatively affects directly social and academic activities, including often failing to offer close attention to details and committing careless mistakes in assignments and homework or during other activities, difficulty maintaining attention in tasks or play, seeming not listening when spoken to directly, failing to follow through instructions or finishing schoolwork, problems with task an activities organization, avoiding or being reluctant to engage in issues calling for sustained mental effort, losing things needed for particular tasks, being easily distracted by external stimuli, and indicating forgetfulness in daily activities (Abuse & Administration, 2018). Regarding hyperactivity and impulsivity, the DSM-5 criteria require a patient to indicate at least six of the following symptoms: being fidgety or tapping hands or feet or moving in the seat, failing to remain seated when expected, running or climbing inappropriately, inability to remain quiet during play or leisure activities, being on the go and failing to stay still, talking excessively, answering before a question is asked, trouble engaging in turn-taking, and often interrupting or intruding others. The patient displays at least six symptoms of inattention and six of hyperactivity and impulsivity, confirming ADHD diagnosis. (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD)

- 9. Generalized Anxiety Disorder:

Generalized anxiety disorder is marked by excessive, exaggerated anxiety and worries about ordinary events without a clear reason (Munir et al., 2021). About 3.1 percent of the population, or more than 8.8 million children, are affected. While it can begin at any age and progress gradually, the risk is most between the ages of five and middle age. Biological variables, family history, life events, and other stressors contribute to GAD, despite the exact cause being unknown (Toussaint et al., 2020). Excessive, persistent worry and tension, unrealistic views of problems, restlessness or a sense of being “edgy,” difficulty focusing, easily becoming exhausted, increased crankiness or irritability, difficulty sleeping, and muscle tension are all symptoms of general anxiety disorder, according to the DMS-5 criteria. People with GAD frequently anticipate disaster and are overly concerned with everyday events such as work. GAD is diagnosed when a person cannot control their worrying, which was refuted in this case because the patient did not exhibit persistent worry and tension.

- 23. Adjustment Disorder:

Those who have trouble adjusting after a stressful event at a degree disproportionate to the severity or intensity of the stressor are said to have adjustment disorder (AD), defined as a maladaptive emotional and/or behavioral reaction to a recognized psychosocial stressor. Stress responses that are inconsistent with socially or culturally expected responses to the stressor and/or that significantly affect every day functioning are characteristics of AD symptoms (O’Donnell et al., 2019). The criteria for adjustment disorder do not include any prerequisites for what might be regarded as a stressor, in contrast to the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress disorder (ASD), which clearly define what constitutes a traumatic experience. Per the DSM-5 criteria, a diagnosis is established when an individual indicates emotional or behavioral symptoms development to respond to stressor(s) occurring within three months of the stressor(s) onset. The second criterion requires the symptoms to be clinically significant, as indicated by considerable stress that is unproportional to the stressor(s) severity or intensity, considering external context and cultural aspects that would influence symptom severity and presentation and the patient to indicate severe impairment ins social, occupation, and other fundamental functioning areas (Abuse & Administration, 2017). The third criterion requires stress-related disturbances not to meet criteria for another mental condition and are minimally affected by a preexisting mental condition. The symptoms should also not represent typical bereavement. (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD)

PLAN:

The patient would benefit from a combination of pharmacological interventions and psychotherapy.

Pharmacological Interventions:

To address ADHD symptoms, start Buspar 10 mg 1 tab PO BID. Also, prescribe venlafaxine 18.75-75 mg/day; may increase to 150 mg/day after 4 weeks and Bupropion Initial: 150 mg/day PO. Give imipramine 75 PO qDay initially; may increase to 150 mg/day gradually and metadate CD: Initial, 20 mg PO qAM before breakfast. Atomoxetine 40 mg PO once daily initially; increase after ≥3 days to 80 mg PO once daily or divided q12hr can also help manage ADHD symptoms.

Psychotherapy

Behavioral psychotherapy is needed to enhance executive function and improve ADHD symptoms. ADHD symptoms can be reduced with the help of psychosocial interventions, such as short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy, applied relaxation interpersonal psychotherapy, and social skills training. Cognitive-behavioral therapy will help reduce restlessness sensations that arise when performing tasks, improve focus and time management, and improve organization (Lopez et al., 2018).

Patient education

- Talk to the patient and parent about risks and benefits of medication, including non-treatment, probable side effects.

- Discuss with patient and parent when to stop medication, how to recognize and when to report adverse events.

- Talk to the patient and parent about the dangers of combining prescription pharmaceuticals with other substances.

- Educate patient and parent to develop structured daily routines, daily schedule, and minimize changes.

- Engage patient in skills training.

- Encourage patient to make time for exercise every day.

- Teach patient and parent to create a system for prioritizing the day and create deadlines for activities.

Follow-up: Patient should follow-up after one week.

Reflection

ADHD is common among children, affecting their social and cognitive functioning. Dealing with ADHD patients, particularly children, can be challenging because it is difficult to make an inquiry or sustain a conversation when the patient is easily distracted by extraneous stimuli, cannot stay still, has difficulty paying attention, and shifts from one thing to another, necessitating parental intervention. Patients are defiant and can be aggressive, refusing to follow instructions and having emotional outbursts. In this case, the patient was polite, which helped establish a rapport and framework for the interview. The mother was of great help in answering the questions to help understand the patient’s condition and how it affects her life. Hyperactivity and inattention symptoms present providers with ethical conflicts between justice and beneficence or non-maleficence. Therapeutic use for ADHD in minors presents ethical issues, including safety, risk/benefit ratio, informed consent, nonmedical use, and labeling problems. Given another chance with the patient, I would inquire more about the family history of ADHD and coping mechanisms or interventions adopted at home and school to help address challenges presented in ADHD patients. (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation of ADHD)

References

Abuse, S., & Administration, M. H. S. (2017). Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Abuse, S., & Administration, M. H. S. (2018). DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance [Internet].

Lopez, P. L., Torrente, F. M., Ciapponi, A., Lischinsky, A. G., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Rojas, J. I., Romano, M., & Manes, F. F. (2018). Cognitive-behavioural interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD010840. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010840.pub2

Magnus, W., Nazir, S., Anilkumar, A. C., & Shaban, K. (2017). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Munir, S., Takov, V., & Coletti, V. A. (2021). Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Nursing). StatPearls [Internet].

O’Donnell, M. L., Agathos, J. A., Metcalf, O., Gibson, K., & Lau, W. (2019). Adjustment Disorder: Current Developments and Future Directions. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(14), 2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142537

Toussaint, A., Hüsing, P., Gumz, A., Wingenfeld, K., Härter, M., Schramm, E., & Löwe, B. (2020). Sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7). Journal of affective disorders, 265, 395-401.

Do you need a similar assignment done for you from scratch? Order now!

Use Discount Code "Newclient" for a 15% Discount!