Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Causes

Black Fungus, or mucormycosis, is primarily caused by fungi belonging to the order Mucorales, with Rhizopus species being the most common culprit. These fungi are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found in soil, decaying organic matter, and even on fruits and vegetables.

Individuals with weakened immune systems are at a heightened risk of developing mucormycosis. This includes patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, especially those with diabetic ketoacidosis, as elevated blood sugar levels provide an ideal environment for fungal growth. Additionally, individuals undergoing treatment with immunosuppressive medications, such as corticosteroids or chemotherapy, are more susceptible to fungal infections due to their compromised immune response.

Furthermore, certain medical conditions and procedures can predispose individuals to mucormycosis. Organ transplant recipients, particularly those receiving lung or stem cell transplants, are at an increased risk due to the immunosuppressive therapy required to prevent organ rejection. Similarly, individuals with hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia or lymphoma, are susceptible to mucormycosis, especially during periods of chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression.

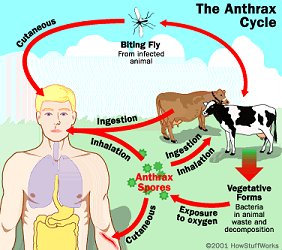

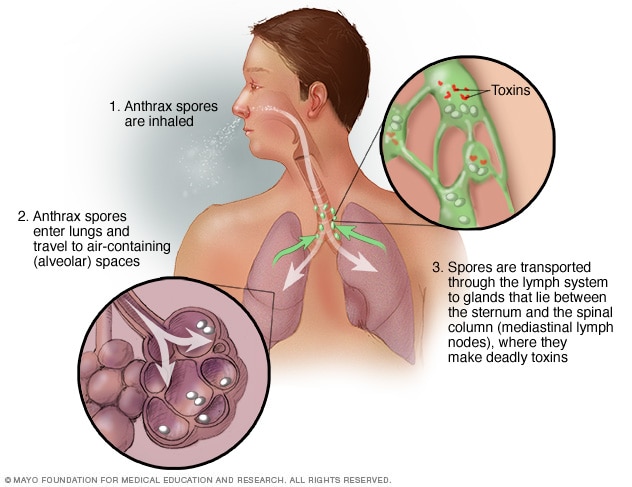

Inhalation of fungal spores is the most common route of infection, particularly among immunocompromised individuals. Spores can enter the body through the respiratory tract, leading to sinus or pulmonary mucormycosis. In some cases, mucormycosis can also occur as a result of direct inoculation into the skin, such as through trauma or surgical wounds.

Overall, while mucormycosis is considered a rare infection, its incidence has been on the rise, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased use of immunosuppressive therapies. Understanding the underlying causes and risk factors associated with Black Fungus is essential for early recognition, prompt treatment, and prevention of this potentially life-threatening condition. (Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical presentation of Black Fungus, or mucormycosis, can vary depending on the site of infection and the individual’s immune status. However, certain signs and symptoms are commonly observed among affected individuals.

Facial swelling is a hallmark feature of rhinocerebral mucormycosis, the most common form of mucormycosis. Patients may experience unilateral or bilateral facial swelling, often accompanied by pain, tenderness, and numbness in the affected area. As the infection progresses, nasal congestion and discharge may develop, sometimes accompanied by black necrotic lesions on the nasal bridge or palate.

Headache is another common symptom, particularly in cases of rhinocerebral mucormycosis where the infection spreads to the sinuses and adjacent structures. Patients may describe the headache as severe and persistent, often worsening over time.

Respiratory symptoms can occur in cases of pulmonary mucormycosis, characterized by fever, cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath. These symptoms may mimic those of other respiratory infections, making early diagnosis challenging.

Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss may also be present, especially in cases where the infection disseminates to other organs or tissues.

In severe cases, mucormycosis can lead to tissue necrosis and thrombosis of blood vessels, resulting in tissue infarction and organ dysfunction. This can manifest as black eschars or gangrenous lesions on the skin, particularly in cutaneous mucormycosis.

It is important to note that mucormycosis can progress rapidly and lead to serious complications if left untreated. Therefore, prompt recognition of the signs and symptoms is crucial for early intervention and improved patient outcomes. Healthcare professionals should maintain a high index of suspicion for mucormycosis, especially in immunocompromised individuals or those with underlying risk factors, and initiate appropriate diagnostic and treatment measures promptly. (Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Etiology

The etiology of Black Fungus, or mucormycosis, is primarily attributed to fungi belonging to the order Mucorales, with Rhizopus species being the most common causative agents. These fungi are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found in soil, decaying organic matter, and various food sources.

The pathogenesis of mucormycosis begins with the inhalation or direct inoculation of fungal spores into the body. Individuals with weakened immune systems, particularly those with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, are at an increased risk of developing mucormycosis due to their compromised immune response. Elevated blood sugar levels in diabetic patients create an ideal environment for fungal growth, facilitating the invasion and proliferation of Mucorales fungi.

Moreover, immunosuppressive medications such as corticosteroids and chemotherapy drugs further predispose individuals to mucormycosis by impairing their immune defenses against fungal infections. Organ transplant recipients, especially those undergoing lung or stem cell transplants, are also at a heightened risk due to the immunosuppressive therapy required to prevent organ rejection.

In addition to immunosuppression, certain medical conditions and procedures can increase the susceptibility to mucormycosis. Patients with hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia or lymphoma, are particularly vulnerable, as are those with iron overload disorders or chronic renal failure.

Furthermore, environmental factors play a significant role in the etiology of mucormycosis. Exposure to contaminated environments, such as construction sites or areas with heavy organic debris, can increase the risk of fungal spore inhalation. Additionally, traumatic injuries or surgical procedures that breach the skin barrier can provide a portal of entry for Mucorales fungi, leading to localized or disseminated infections.

Overall, a combination of host factors, environmental exposure, and immunosuppression contributes to the etiology of mucormycosis, highlighting the importance of understanding these underlying factors in preventing and managing this potentially life-threatening fungal infection. (Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of Black Fungus, or mucormycosis, involves a complex interplay between host factors, fungal virulence, and environmental conditions. Understanding the pathogenesis of mucormycosis is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms of disease progression and guiding therapeutic interventions.

The initial step in the pathophysiology of mucormycosis is the inhalation or direct inoculation of fungal spores into the body. These spores, primarily belonging to the order Mucorales and commonly of Rhizopus species, adhere to mucosal surfaces in the respiratory tract or skin and invade surrounding tissues.

Once inside the host, Mucorales fungi exhibit angioinvasive properties, meaning they can invade and destroy blood vessels. This angioinvasion leads to tissue infarction and necrosis, characterized by thrombosis of small blood vessels and subsequent ischemic injury. The rapid proliferation of fungi within blood vessels contributes to the dissemination of infection to other organs and tissues, leading to systemic manifestations of disease.

Furthermore, Mucorales fungi have a predilection for tissues with high glucose levels, such as those seen in uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Elevated blood sugar levels provide an ideal environment for fungal growth and facilitate the invasion of Mucorales fungi into the host tissues.

The host’s immune response plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of mucormycosis. Individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those with uncontrolled diabetes or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, are particularly susceptible to fungal infections. Impaired phagocytic function and decreased production of reactive oxygen species contribute to the inability of the immune system to effectively clear the fungal pathogens, allowing for unchecked fungal proliferation and tissue invasion.

Overall, the pathophysiology of mucormycosis involves a multifactorial process encompassing fungal virulence, host immune response, and environmental factors. Elucidating these mechanisms is essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at combating this life-threatening fungal infection. (Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

DMS-5 Diagnosis

Diagnosing Black Fungus, or mucormycosis, involves a comprehensive evaluation based on clinical presentation, imaging studies, and histopathological examination. While the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), primarily focuses on mental health conditions, the diagnosis of mucormycosis is established through clinical criteria and laboratory findings.

The DSM-5 does not provide specific criteria for mucormycosis diagnosis; instead, healthcare professionals rely on established clinical guidelines and evidence-based practices. The diagnosis is predominantly clinical, with a detailed assessment of the patient’s medical history, presenting symptoms, and risk factors.

Imaging studies, such as computed tomography (CT) scans, play a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis. Characteristic findings on imaging may include sinus involvement, pulmonary infiltrates, or evidence of tissue necrosis. These imaging modalities help visualize the extent of the infection and guide further diagnostic interventions.

Histopathological examination, often through biopsy, is a key component of mucormycosis diagnosis. Tissue samples are obtained from the affected site, and histopathological analysis reveals characteristic fungal elements, such as broad, non-septate hyphae with right-angle branching. This microscopic identification of the causative fungi, typically belonging to the Mucorales order, confirms the presence of mucormycosis.

In addition to histopathology, cultures, and molecular methods may be employed to identify the specific species of Mucorales fungi, providing valuable information for targeted antifungal therapy.

While the DSM-5 may not directly guide the diagnosis of mucormycosis, a multidisciplinary approach involving clinical, imaging, and laboratory assessments is essential for accurate and timely identification of this potentially life-threatening fungal infection. Incorporating these diagnostic modalities ensures a comprehensive understanding of the disease, enabling healthcare professionals to initiate prompt and effective therapeutic interventions. (Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Treatment Regimens and Patient Education

Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are essential in managing Black Fungus, or mucormycosis, and improving patient outcomes. The treatment approach typically involves a combination of antifungal medications, surgical intervention, and supportive care. Additionally, patient education plays a crucial role in preventing and managing mucormycosis, particularly in high-risk populations.

Antifungal Medications: The cornerstone of mucormycosis treatment is antifungal therapy, with amphotericin B being the primary agent of choice. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B, such as liposomal amphotericin B, are preferred due to their lower nephrotoxicity compared to conventional formulations. Posaconazole, an oral triazole antifungal agent, is often used as salvage therapy in cases of refractory or intolerant disease.

Surgical Debridement: Surgical debridement is an integral part of mucormycosis management, particularly in cases of localized disease or when there is extensive tissue involvement. Prompt surgical intervention aims to remove necrotic tissue and control the spread of infection, thereby improving the efficacy of antifungal therapy and reducing the risk of complications.

Supportive Care: Supportive care measures, including management of underlying medical conditions and optimization of immune function, are crucial in enhancing the patient’s overall prognosis. Diabetic management, control of hyperglycemia, and discontinuation of immunosuppressive medications, when feasible, are essential strategies for preventing disease recurrence and promoting healing.

Patient Education: Patient education plays a pivotal role in preventing mucormycosis and optimizing treatment outcomes, especially in individuals with predisposing risk factors. Patients with diabetes mellitus should receive comprehensive education on glycemic control, foot care, and the importance of regular medical follow-ups to monitor for signs of infection.

Furthermore, individuals undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, such as corticosteroids or chemotherapy, should be educated about the increased risk of fungal infections and the importance of adherence to prescribed medications. Patient education should emphasize the early recognition of symptoms, such as facial swelling, headache, nasal congestion, and black lesions, and prompt reporting to healthcare providers for timely evaluation and intervention.

The management of mucormycosis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving antifungal therapy, surgical intervention, and supportive care measures. Patient education is paramount in preventing mucormycosis and optimizing treatment outcomes by promoting early recognition of symptoms and adherence to preventive measures. By addressing both therapeutic and educational aspects, healthcare providers can effectively manage mucormycosis and improve patient outcomes. (Nursing Paper Example on Black Fungus: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment)