Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder

/in Assignment Help, Assignment Help Nursing, BLOG, Homework Help, Nursing Exam Help, Nursing Paper Help, Solved Nursing Essays /by Aimee GraceNursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurological disorder that affects the nerve cells responsible for controlling voluntary muscle movements. This condition, first described by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot in the 19th century, is characterized by the gradual degeneration of motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord. As these neurons deteriorate, individuals with ALS experience muscle weakness, twitching, and eventually paralysis, ultimately leading to respiratory failure and death within a few years of diagnosis. Despite extensive research, the exact cause of ALS remains elusive, with both genetic and environmental factors implicated in its development. ALS poses significant challenges for patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals due to its devastating impact on physical function and quality of life. In this paper, we will explore the causes, signs and symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, DSM-5 diagnosis, treatment regimens, patient education, and implications of ALS, aiming to deepen our understanding of this debilitating neurological condition. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

Causes

The exact cause of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) remains a subject of ongoing research, but it is widely accepted that a combination of genetic and environmental factors contributes to its development.

Genetic Factors: Approximately 5-10% of ALS cases are familial, meaning they are inherited from a parent who carries a specific genetic mutation associated with the disease. Several genes have been identified as potential contributors to familial ALS, including SOD1, C9orf72, TARDBP, and FUS. Mutations in these genes disrupt normal cellular processes, leading to the degeneration of motor neurons and the progression of ALS symptoms.

Environmental Factors: While the majority of ALS cases are sporadic, meaning they occur without a clear familial link, environmental factors may still play a role in their development. Exposure to certain toxins and chemicals, such as lead, mercury, pesticides, and heavy metals, has been associated with an increased risk of ALS. Additionally, trauma or injury to the central nervous system, such as head injuries or repetitive physical activities, may also contribute to the onset of ALS symptoms in some individuals.

Gene-Environment Interactions: Emerging evidence suggests that interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures may influence the development of ALS. For example, individuals with specific genetic mutations may be more susceptible to the effects of environmental toxins, leading to an increased risk of developing ALS. Conversely, environmental factors may trigger or exacerbate the progression of ALS symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals.

While the exact cause of ALS remains elusive, research into the interplay between genetic and environmental factors continues to provide valuable insights into the pathogenesis of the disease. By understanding the complex interactions that contribute to ALS development, researchers hope to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies for the prevention and treatment of this devastating neurological disorder. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

Signs and Symptoms

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is characterized by a progressive deterioration of motor function, resulting in a range of signs and symptoms that impact voluntary muscle movements. The onset of ALS is often insidious, with symptoms gradually worsening over time.

Muscle Weakness: One of the earliest signs of ALS is muscle weakness, which typically begins in the limbs and gradually spreads to other parts of the body. Initial weakness may manifest as difficulty performing tasks that require fine motor control, such as buttoning a shirt or holding objects.

Muscle Twitching and Cramping: Individuals with ALS often experience muscle twitching, known as fasciculations, and muscle cramping, particularly in the arms and legs. These involuntary muscle contractions may be a source of discomfort and contribute to muscle fatigue.

Difficulty Speaking and Swallowing: As ALS progresses, weakness in the muscles involved in speech and swallowing becomes more pronounced. Speech may become slurred or difficult to understand, and individuals may have trouble swallowing food and liquids, leading to choking or aspiration.

Respiratory Symptoms: ALS eventually affects the muscles responsible for breathing, leading to respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, and frequent respiratory infections. Respiratory muscle weakness is a significant complication of ALS and often requires interventions such as mechanical ventilation to support breathing.

Muscle Atrophy: As motor neurons degenerate in ALS, affected muscles undergo atrophy, or shrinkage, due to disuse and loss of nerve stimulation. Muscle atrophy contributes to weakness and can lead to visible changes in muscle size and shape.

Progressive Disability: Over time, the combination of muscle weakness, atrophy, and respiratory compromise results in progressive disability in individuals with ALS. Once routine tasks become increasingly challenging, and eventually, individuals may require assistance with activities of daily living.

The signs and symptoms of ALS vary from person to person but generally involve progressive muscle weakness, twitching, difficulty speaking and swallowing, respiratory impairment, and muscle atrophy. Early recognition of these symptoms is crucial for timely diagnosis and intervention to improve the quality of life for individuals living with ALS. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

Etiology

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a complex neurological disorder with a multifactorial etiology involving genetic, environmental, and potential gene-environment interactions.

Genetic Factors: A subset of ALS cases, approximately 5-10%, are familial, meaning they have a clear genetic component. Mutations in several genes have been identified as contributing to familial ALS, including SOD1, C9orf72, TARDBP, and FUS. These genetic mutations disrupt normal cellular processes, leading to the degeneration of motor neurons and the progression of ALS symptoms. Although familial ALS accounts for a relatively small proportion of cases, the study of familial ALS has provided valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of the disease.

Environmental Factors: While the majority of ALS cases are sporadic, meaning they occur without a clear familial link, environmental factors may still play a role in disease development. Exposure to certain toxins and chemicals, such as lead, mercury, pesticides, and heavy metals, has been associated with an increased risk of ALS. Additionally, trauma or injury to the central nervous system, such as head injuries or repetitive physical activities, may also contribute to the onset of ALS symptoms in some individuals.

Gene-Environment Interactions: Emerging evidence suggests that interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures may influence the development of ALS. For example, individuals with specific genetic mutations may be more susceptible to the effects of environmental toxins, leading to an increased risk of developing ALS. Conversely, environmental factors may trigger or exacerbate the progression of ALS symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals.

The etiology of ALS is complex and multifaceted, involving a combination of genetic and environmental factors, as well as potential gene-environment interactions. Understanding the interplay between these factors is crucial for unraveling the underlying mechanisms of ALS and identifying novel therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of this devastating neurological disorder. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

Pathophysiology

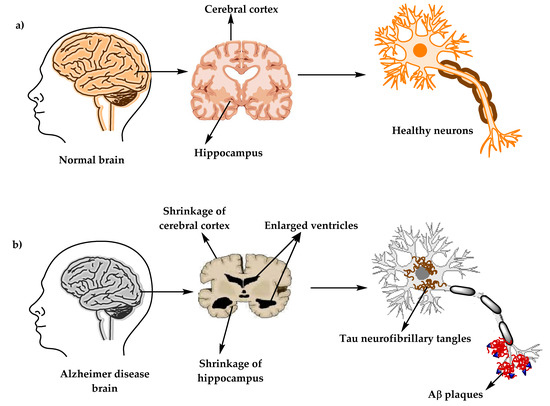

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is characterized by the progressive degeneration of motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord, leading to muscle weakness and eventual paralysis. The pathophysiology of ALS involves various cellular and molecular mechanisms that contribute to the selective loss of motor neurons.

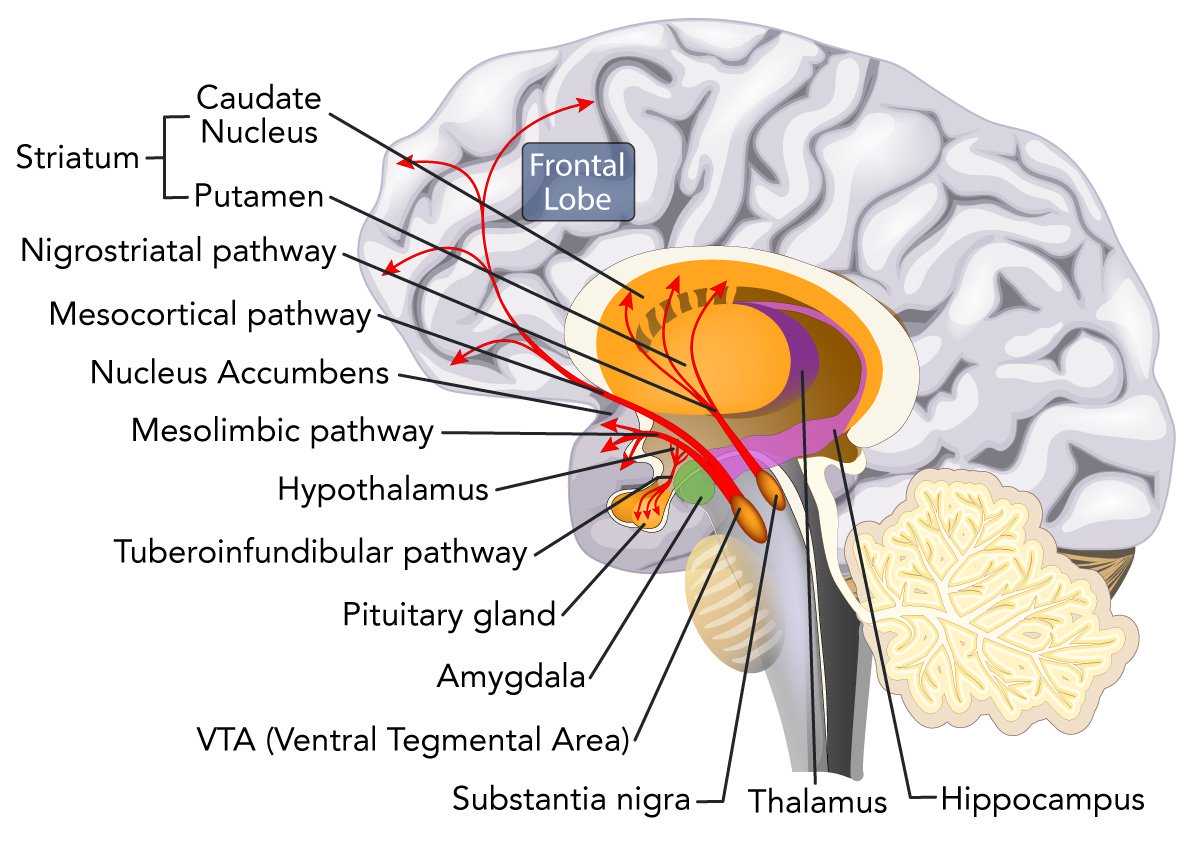

Excitotoxicity: Glutamate, a neurotransmitter involved in signal transmission between neurons, plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of ALS. In ALS, excessive levels of glutamate accumulate in the synaptic cleft, leading to excitotoxicity and subsequent damage to motor neurons. This excitotoxicity is thought to result from impaired glutamate uptake and clearance mechanisms, ultimately contributing to neuronal death.

Oxidative Stress: Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant defense mechanisms, is another key feature of ALS pathophysiology. Motor neurons are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage due to their high metabolic activity and limited antioxidant capacity. Oxidative stress leads to cellular dysfunction and neuronal death, further exacerbating the progression of ALS.

Protein Aggregation: Abnormal protein aggregation is a hallmark of ALS pathology, with misfolded proteins accumulating within motor neurons and forming intracellular inclusions. One of the most well-known proteins associated with ALS pathology is superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), the mutation that is linked to familial ALS. Other proteins, such as TDP-43 and FUS, are also implicated in ALS pathogenesis and contribute to protein aggregation and neurotoxicity.

Neuroinflammation: Inflammation within the central nervous system is a prominent feature of ALS pathology, with microglia and astrocytes playing key roles in the neuroinflammatory response. Dysregulated immune responses and inflammatory mediators contribute to neuronal injury and exacerbate the progression of ALS.

The pathophysiology of ALS is complex and multifaceted, involving excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, protein aggregation, and neuroinflammation. Understanding these underlying mechanisms is essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at slowing the progression of ALS and improving outcomes for affected individuals. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

DSM-5 Diagnosis

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association, does not provide specific diagnostic criteria for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) as it is a neurological disorder rather than a psychiatric condition. However, ALS can present with symptoms that may overlap with certain psychiatric or psychological manifestations, necessitating careful evaluation and differential diagnosis.

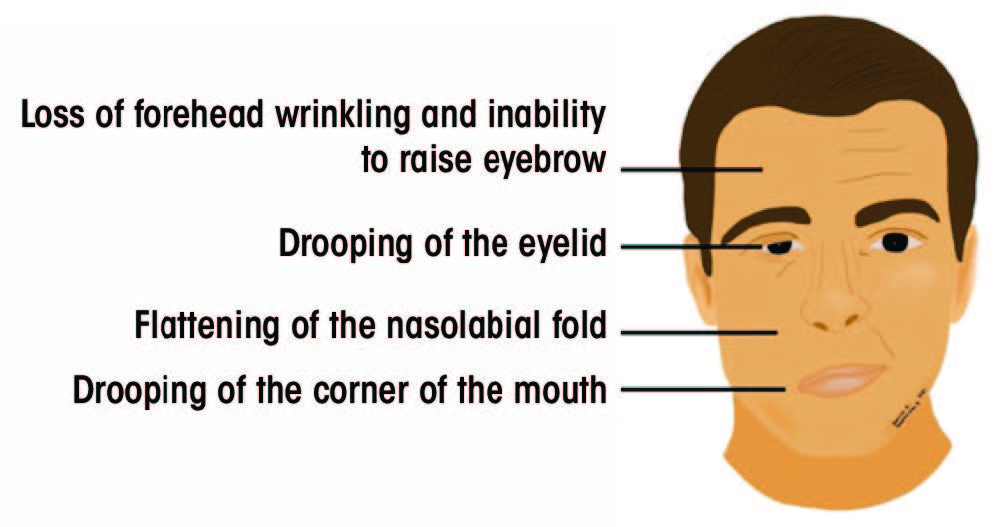

Clinical Presentation: Diagnosis of ALS typically relies on clinical presentation and neurological examination findings. Common symptoms include progressive muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, fasciculations (muscle twitching), and impaired motor function. Individuals may also experience difficulty with speech, swallowing, and respiratory function as the disease progresses.

Neurological Examination: A thorough neurological examination is essential for diagnosing ALS and distinguishing it from other neurological conditions with similar symptoms. Neurological assessments may include tests of muscle strength, reflexes, coordination, and sensation, as well as electromyography (EMG) to assess electrical activity in muscles.

Exclusion of Other Conditions: Diagnosis of ALS involves ruling out other potential causes of motor neuron dysfunction and muscle weakness. Conditions that may mimic ALS include spinal cord disorders, peripheral neuropathies, muscular dystrophies, and other motor neuron diseases.

Electrodiagnostic Testing: Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies are commonly used to evaluate nerve and muscle function in individuals suspected of having ALS. These tests can help identify abnormalities in electrical activity within muscles and nerves, supporting the diagnosis of ALS.

Imaging Studies: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other neuroimaging modalities may be used to assess structural changes in the brain and spinal cord, although they are not typically required for the diagnosis of ALS.

The diagnosis of ALS is primarily based on clinical presentation, neurological examination findings, and exclusion of other potential causes of motor neuron dysfunction. While the DSM-5 does not provide specific diagnostic criteria for ALS, accurate diagnosis is essential for initiating appropriate management and support for individuals affected by this devastating neurological disorder. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

Treatment Regimens and Patient Education

While there is currently no cure for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), various treatment regimens and supportive measures can help manage symptoms, improve quality of life, and provide comfort for individuals living with the disease. Additionally, patient education plays a crucial role in empowering patients and their caregivers to navigate the challenges associated with ALS effectively.

Multidisciplinary Care: The management of ALS often involves a multidisciplinary approach, with a team of healthcare professionals collaborating to address the diverse needs of patients. This team may include neurologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, respiratory therapists, nutritionists, social workers, and palliative care specialists.

Symptom Management: Medications such as riluzole and edaravone may be prescribed to slow the progression of ALS and prolong survival, although their efficacy is limited. Symptomatic treatment aims to alleviate specific symptoms associated with ALS, such as muscle spasticity, pain, cramps, excessive saliva production, and respiratory difficulties.

Physical Therapy: Physical therapy plays a crucial role in maintaining mobility, preventing muscle contractures and deformities, and optimizing functional independence in individuals with ALS. Therapeutic exercises, range-of-motion activities, assistive devices, and adaptive equipment may be recommended to address specific needs and goals.

Speech and Swallowing Therapy: Speech-language pathologists provide interventions to address communication difficulties and swallowing dysfunction commonly observed in individuals with ALS. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices, speech therapy exercises, and dietary modifications may be prescribed to optimize communication and nutrition.

Respiratory Support: Respiratory therapists play a key role in managing respiratory complications associated with ALS, such as respiratory muscle weakness and impaired lung function. Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) and mechanical ventilation may be initiated to support breathing and improve respiratory function, particularly during sleep or periods of respiratory distress.

Nutritional Support: Nutritionists and dietitians collaborate with individuals with ALS to address nutritional needs, maintain adequate calorie intake, and prevent malnutrition and weight loss. Strategies such as modified diets, oral supplements, and enteral feeding may be recommended to support optimal nutrition and hydration.

Psychosocial Support: Social workers and mental health professionals provide emotional support, counseling, and resources to individuals with ALS and their caregivers. Psychosocial support aims to address the emotional, social, and psychological challenges associated with ALS and promote coping strategies and resilience.

Patient Education: Patient education is essential for empowering individuals with ALS and their caregivers to make informed decisions about their care, manage symptoms effectively, and optimize quality of life. Education topics may include disease progression, symptom management, medication adherence, adaptive strategies, communication techniques, nutritional guidance, respiratory care, end-of-life planning, and available support services and resources.

Treatment regimens for ALS focus on symptom management, supportive care, and enhancing quality of life through a multidisciplinary approach. Patient education plays a crucial role in empowering individuals with ALS and their caregivers to navigate the challenges associated with the disease effectively and access the necessary support and resources to optimize care and well-being. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

Conclusion

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a devastating neurological disorder characterized by progressive muscle weakness and paralysis. While the exact cause remains elusive, a combination of genetic and environmental factors contributes to its development. Understanding the causes, signs and symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, DSM-5 diagnosis, treatment regimens, patient education, and implications of ALS is crucial for effectively managing this complex condition. The changes made in the essay, including the exploration of treatment regimens and the emphasis on patient education, underscore the importance of a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to ALS care. By addressing symptoms, optimizing quality of life, and providing support for individuals with ALS and their caregivers, healthcare professionals can make a meaningful difference in the lives of those affected by this challenging disease. Ongoing research and advancements in ALS management offer hope for improved outcomes and a brighter future for individuals living with ALS. (Nursing Paper Example on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Understanding a Devastating Neurological Disorder)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/rehabilitation-therapies-for-multiple-sclerosis-4072854-e72137c8397a4d909ce759135c9fa3a8.png)