Paper Human Sexuality homework help

Preface

This past year was tough, making the switch to LeVay et al., but I’m glad I did it. Discovering Human Sexuality is unique in both approach and content. The authors have a point of view, but still provide balanced coverage of contro- versial issues. The boxes are wonderful. One of the things I like about it is the inclusion of historical and cross-cultural detail in the boxes. It’s a very readable and beautiful book. The illustrations and diagrams are excellent—the best of any text I have ever used. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Josephine Caldwell-Ryan Southern Methodist University

Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition, is the continuation of a textbook that originated in 2003 with the publication of Human Sexuality by Simon LeVay and Sharon Valente. Since then, the book has gone through several changes of author- ship, format, and title. One consistency, however, has been the identity of the lead author. Another has been the book’s high academic and pedagogical standards, which have earned it a prominent place in the market and broad praise from review- ers and users, including the kind words cited above.

The Second Edition of Human Sexuality appeared in 2006 with the same two authors. For the 2009 edition, however, Janice Baldwin replaced Sharon Valente. Also, we decided to produce two distinct versions of the book. One of them— Human Sexuality, Third Edition—continued the approach pioneered in the earlier editions. The other, which we titled Discovering Human Sexuality, was a somewhat shorter and more accessible version that demanded less prior knowledge on the part of the students, especially in the area of biol- ogy. John Baldwin joined LeVay and Janice Baldwin as third author of this version. In 2012 we continued with the same two versions (Human Sexuality, Fourth Edition, and Discover- ing Human Sexuality, Second Edition).

For the current edition we have decided to merge the two versions into one, which we have titled Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition. It was a difficult decision to make because both versions had been successful in the market- place and each served a somewhat different need. However, the workload involved in producing two different textbooks at the same time was excessive. In addition, we realized that we could incorporate the best features of Human Sexuality into Discovering Human Sexuality by judicious changes to the text and by the addition of two appendices containing more advanced “optional” material.

Features of Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition Important features of Discovering Human Sexuality distinguish our book from competing texts: (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

evidence-based approach We believe that human sexuality is an academic subject like any other, meaning that it should be grounded in reason. Throughout the book, we have sought to present statements that are supported by data, ideas that are tested or testable, and recommendations that are based on research. There are many unanswered questions in sexuality, of course—questions about how ab- normal modes of sexual expression (paraphilic disorders) develop, for example, and how best to treat them. In deal- ing with these controversies, an evidence-based approach demands a nondogmatic style and a willingness to admit that not everything is known. Some students may feel chal- lenged to enter the field of sex research themselves in order to help fill those gaps in our understanding.

Some human sexuality texts contain a great deal of advice to students, especially in the area of relationships. Much of this advice has no objective basis and seems designed more to transmit the authors’ values than to foster an authentic learning experience. In Discovering Human Sexuality, we keep the total quantity of advice down and try to ensure that the advice we do give has been “field-tested.” Even in such an elementary matter as how to put on a condom, many texts include useless steps, such as squeezing the tip of the con- dom to leave space for the ejaculate. Doing so serves no pur- pose—the man who could burst a condom with his ejaculate has yet to be born—and neither the World Health Organiza- tion nor the leading U.S. experts believe that it should be part of the instructions for condom use. It has become an element in the folklore that gets perpetuated by textbooks— though not by this one. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Literature citations are, of course, an important element of an evidence-based book. We have been surprised by how cavalierly some competing books deal with this issue—quite commonly, citations in the text are not matched by any cor- responding entries in the bibliography. In Discovering Human Sexuality we have made every effort to ensure that references are fully documented. Another common practice that we consider unacademic is referring to original research stud- ies by citing magazine or newspaper articles that mention

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 21 1/20/15 12:27 PM

xxII PREFACE

them, rather than the journal articles in which the research was presented. Our policy has been to cite original sources wherever possible, and to use magazine and newspaper references for the kinds of topics they excel at, such as news stories, cultural trends, and the like. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help) emphasis on diversity Today’s college students come from a wide range of backgrounds, and in their adult lives they will have to deal with people very different from themselves. Our text presents this diversity in a detailed and nonjudgmental fashion. For example, with regard to sexual orientation, we go far beyond “gay,” “bisexual,” and “straight”: We talk about the ever-changing history of the butch-femme dichotomy in lesbian culture, women whose self-identity is too fluid for one-word labels, gay men who are “bears” or “bear cubs” or into the leather scene, what it’s like to be gay and Asian-American or Native American, how the gay experience differs for different generations of Americans and for gay people around the world, and so on. Similarly, we take pains to discuss racial, ethnic, and religious diversity, as they affect sexuality, and of course diversity in the actual modes of sexual behavior—including some of the more unusual forms of sexual expression such as “adult babies” and men whose partners are (liter- ally) dolls. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help) presentation style Simon LeVay, Janice Baldwin, and John Baldwin are all experienced authors of college text- books. In creating Discovering Human Sexuality, we have pooled our writing skills to ensure that the text is fully accessible, engaging, and relevant to students of diverse back- grounds. The result of these combined efforts is, we believe, the most readable and student-friendly human sexuality text on the market.

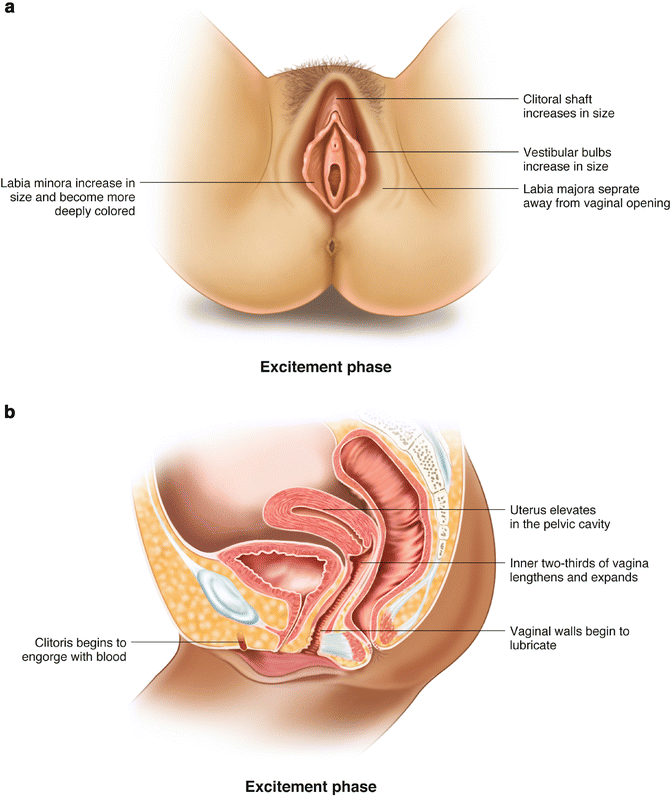

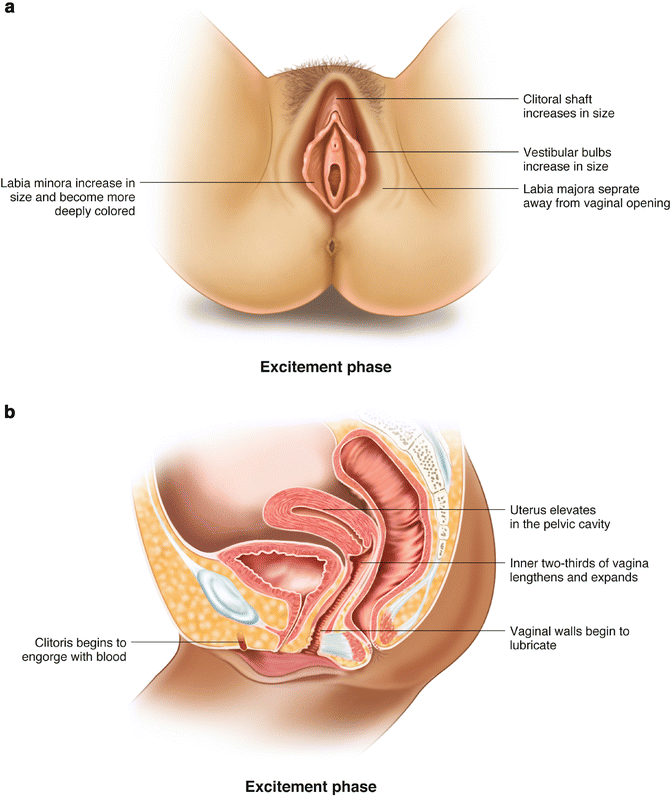

art program Another way that we have striven to maintain both comprehensibility and interest is through the illustrations. One might think that it would be a simple matter to illustrate a book on human sexuality, but in reality it is a significant challenge. Illustrating some of the concepts dis- cussed in this book, especially in its more biologically oriented sections, requires a great deal of thought and design skill. Our publisher, Sinauer Associates, is an industry leader in the use of art as a pedagogical medium. Thanks to our publisher’s efforts, many complex topics, such as the regulation of the menstrual cycle, have been given a visual representation that gracefully parallels and clarifies the accompanying text. Nearly every two-page spread in the book offers one or more illustrations—photographs, drawings, diagrams, graphs, or charts—relevant to the text on that spread. Besides their informative value, illustrations offer important visual relief. Some of our competitors’ texts contain sequences of up to ten pages without a single illustration—a definite challenge to the average student’s attention span. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help) boxes The 76 boxes are an important feature of the book. The boxes are organized into eight themes: Controversies; Biology of Sex; Cultural Diversity; Research Highlights; Sexual Health; Sex in History; Personal Points of View; and Society, Values, and the Law. Within each theme, the sub- jects range from the serious to the lighthearted, but they all attempt to broaden the reader’s horizons with a more in- depth look at specific questions than is possible within the main text: What exactly does “losing one’s virginity” mean to today’s teenagers, behaviorally and emotionally? Is there more than one kind of female ejaculation? What’s it like to be a rubber fetishist? Why do some Amazonian peoples be- lieve that a child can have several fathers? In tackling these and many other questions, the boxes provide breaks from the steady flow of the text and allow students to consider specific issues in a more relaxed and informal way.

Other aids to learning and revision include key terms (indi- cated by boldfaced type and defined in a running glossary), FAQs (frequently asked questions), discussion questions, chapter summaries, Web resources, and recommended reading materials.

Discovering Human Sexuality’s student companion web- site (sites.sinauer.com/discoveringhumansexuality3e) is an invaluable learning aid. This site parallels the text with a thorough set of study questions, animations, activities, Web topics, quizzes, and other resources. Website activities are linked to the text and are referenced in maroon type in the printed text. In addition, a complete set of instructor supple- ments is available to qualified adopters of the textbook. See the section on Media and Supplements for details on the full range of material that accompanies Discovering Human Sexuality.

The Third Edition The following are examples of the many changes that we have made for the Third Edition: zz Chapter 1, “Sexuality: Pathways to Understanding,”

has been thoroughly rewritten. It now pays less attention to the history of sex research and more to the diversity of methods that are used to study sexu- ality. We discuss a specific example of the use of each methodological approach. zz We have added discussions of many topics that

were not covered, or only briefly covered, in earlier editions. These topics include group sex (Chapter 6); data-mining studies based on OkCupid and

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 22 1/20/15 12:27 PM

other websites (Chapters 5, 12, and elsewhere); the influence of physical attractiveness on men’s and women’s satisfaction with their long-term relation- ships (Chapter 5); the new definitions of paraphilias and paraphilic disorders in DSM-5 and the contro- versy surrounding them (Chapter 13); the current debate on how to respond vigorously and yet fairly to allegations of campus rape (Chapter 16); and the personalities and attitudes of men who use prosti- tutes (Chapter 17). We have also deleted numerous passages that seemed less interesting or instructive than they were a few years ago. zz We have added 19 new boxes on a wide range of

topics, including “Foot Orgasms,” “Pain-free Child- birth,” “Feticide,” “Why Gay Genes?” “STIs and the Law,” and “What’s It Like to Be a Porn Star?” zz We have of course taken the opportunity to update

the book with the latest research, surveys, statistics, laws, medical advances, contraceptive techniques, and cultural happenings. zz The two appendices cover material that was not

included in Discovering Human Sexuality, Second Edition. We present this material in the form of appendices so that instructors may include it or not as suits the purposes of their classes and the interests and backgrounds of their students. Appendix A is an abbreviated and updated version of the chapter “Sex and Evolution” from Human Sexuality, Fourth Edi- tion. It tackles important questions that are addressed in few other undergraduate human sexuality text- books, such as: What is the adaptive value of sexual reproduction? How does sexual selection work? What are the benefits and costs of male and female promiscuity? and What is the basis of incest avoid- ance? Appendix B lays out more detail on the role of the nervous system in sexual behavior and physiol- ogy than is presented in the main text, including, for example, the anatomy and functional role of the autonomic nervous system in genital responses. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Acknowledgments Producing a modern college textbook such as this one requires the combined efforts of a much larger team of professionals than the three of us who are privileged to have our names on the front cover. The staff members of Sinauer Associates have produced, with great efficiency and good humor, a textbook of outstanding visual quality and educational value. Those with whom we have had the most enduring contacts are editor Sydney Carroll, produc- tion editor Martha Lorantos, and photo researcher David

McIntyre, but many others labored behind the scenes to ensure the book’s high quality and timely production. We are especially grateful for the production oversight of Janice Holabird and Christopher Small, and for the creative cover design by Joan Gemme. We also thank Lou Doucette for her skillful copyediting; Jason Dirks, Carolyn Mailler, Mara Sil- ver, Suzanne Carter, Ann Chiara, Thomas Friedmann, and Nate Nolet for their work on the media and supplements package; Marie Scavotto, Nancy Asai, and Susan McGlew for their effective work promoting the book; Johanna Walko- wicz for obtaining outside reviews; and Penny Grant for sending us our checks on time!

Reviewers We acknowledge with gratitude the extensive and construc- tive comments made by the people who reviewed chapters of Discovering Human Sexuality for the new edition. These reviewers are listed below. Helpful comments have also come from the Baldwins’ students at the University of Cali- fornia, Santa Barbara.

Ernest Abel, Wayne State University Amy Beeman, San Diego Mesa College Kimberly Blackwell, Hampton University Elizabeth Calamidas, Richard Stockton College Michael Clayton, Youngstown State University Karen Gee, Mission College Samantha Gibeau, Lane Community College John Hallock, Pima Community College Julie Harris, East Carolina University Lynda Hoggan, Mt. San Antonio College Nathan Iverson, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Jason Lavender, North Dakota State University Janet Lever, California State University, Los Angeles Vicki Lucey, Modesto Junior College Stephanie Marin, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Wanda C. McCarthy, University of Cincinnati Clermont College Heather Meggers, Birmingham Southern College Tami James Moore, University of Nebraska at Kearney Peggy Oberstaller, Lane Community College Carolyn Peterson, University of Cincinnati Jason Rothman, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Justine Shuey, Montgomery County Community College Peter Sparks, Oregon State University–Cascades Paul Vasey, University of Lethbridge James Vaughn, University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma

PREFACE xxIII

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 23 1/20/15 12:27 PM

Media and Supplements to accompany Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition

For the Student Companion Website sites.sinauer.com/discoveringhumansexuality3e

The Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition Companion Website includes a robust set of study and review aids—all available at no cost to the student. This online companion to the textbook takes the place of a printed study guide and includes the following resources: zz Chapter Outlines: Complete outlines of each chapter

provide an overview of the chapter and include links to the relevant Study Questions for each section. zz Chapter Summaries: A thorough review of each chap-

ter’s content. zz Learning Objectives: The objectives help focus the

student on the important concepts and topics in each chapter; each is referenced to specific textbook head- ings and pages. zz Activities: For selected chapters, animations, dynamic

illustrations, and labeling exercises help the student learn and understand complex concepts and ana- tomical (and other) terms. zz Study Questions: An extensive set of interactive self-

study questions covers the full range of content in every chapter. zz Flashcards: Students can quiz themselves on all the

important terms from each chapter, or they can browse the list of terms as a review. zz Web Links: A set of online sites and resources relevant

to each chapter. zz Glossary: A complete online version of the book’s

glossary. zz Online Quizzes: Two sets of questions are available

for each chapter, for instructors to assign or make available to students as review exercises (instructor registration required): zz Multiple-Choice Quizzes test student comprehension of the material covered in each chapter. zz Essay Questions challenge students to synthesize and apply what they have learned. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

For the Instructor (available to qualified adopters)

Instructor’s Resource Library The Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition Instructor’s Resource Library (IRL) contains a wealth of resources for use in course planning, lecture development, and assessment. Contents include: zz Textbook Figures & Tables: All of the textbook’s figures

(both line art and photographs) are provided as JPEG files at two sizes: high-resolution (excellent for use in PowerPoint) and low-resolution (ideal for web pages and other uses). All the artwork has been reformatted and optimized for exceptional image quality when projected in class. zz PowerPoint Resources: Two ready-to-use presentations

are provided for each chapter: zz A lecture presentation that includes text covering the entire chapter, with selected figures. zz A figures presentation that includes all the figures and tables from the chapter. zz Instructor’s Manual: The Instructor’s Manual provides instructors with a variety of resources to aid in planning their course and developing their lectures. For each chapter, the manual includes a chapter overview, a chapter outline, the complete chap- ter summary, class discussion questions, teaching resources, and suggested readings. zz Media Guide: The Media Guide includes extensive lists of suggested video segments (and full-length titles) that are ideal for use as lecture starters or other in-class activities. Video suggestions (with links and sources) are provided for topics across all chap- ters, and suggested discussion questions are also included. zz Test Bank: The Test Bank consists of a broad range of questions covering all the key facts and concepts in each chapter. Each chapter includes multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, and, new for the Third Edition, short answer questions. Also included are all of the Companion Website quizzes (multiple-choice and essay), the textbook end-of-chapter questions, and

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 24 1/20/15 12:27 PM

MEDIA AND SUPPLEMENTS xxV

the Media Guide discussion questions. All questions are keyed to Bloom’s Taxonomy and referenced to specific textbook sections. zz Computerized Test Bank: The entire test bank is pro-

vided in Blackboard’s Diploma software. Diploma makes it easy to assemble quizzes and exams from any combination of publisher-provided questions and instructor-created questions. In addition, quiz- zes and exams can be exported to many different course management systems, such as Blackboard and Moodle.

Online Quizzing The Discovering Human Sexuality Companion Website fea- tures pre-built chapter quizzes (see above) that report into an online gradebook. Adopting instructors have access to these quizzes and can choose to either assign them or let students use them for review. (Instructors must register in order for their students to be able to take the quizzes.) Instructors also have the ability to add their own questions and create their own quizzes.

Value Options eBOOK Discovering Human Sexuality, Third Edition is available as an eBook, in several different formats. The eBook can be pur- chased as either a 180-day rental or a permanent (non-expir- ing) subscription. All major mobile devices are supported. For details on the eBook platforms offered, please visit www. sinauer.com/ebooks.

Looseleaf Textbook (ISBN 978-1-60535-379-1) Discovering Human Sexuality is available in a three-hole punched, looseleaf format. Students can take just the sec- tions they need to class and can easily integrate instructor material with the text.

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 25 1/20/15 12:27 PM

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 26 1/20/15 12:27 PM

Discovering Human Sexuality

third edition

00_DHS3E_Frontmatter2.indd 1 1/20/15 12:27 PM

1Chapter

Sexuality is a fundamental aspect of human nature.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 2 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: Pathways to Understanding

Sexuality is a central and all-pervasive theme of human existence. At its best, sexuality charges our lives with energy, excitement, and love. It offers a deep sense of connectedness, capable of spanning and healing social divisions. It creates family, the primary unit of society and the cradle of future generations.

At its worst, sexuality brings prejudice, anguish, violence, and disease. To begin our exploration of this powerful and mysterious force, we first ask what the terms “sex” and “sexuality” mean and why sexuality is a topic worth studying. We go on to review some of the ways in which human sexuality has changed between the origin of our species and the present day. Our purpose is to make clear that, even though there may be some eternal truths about sexuality, it is not static: It changes slowly as a result of evolutionary forces, and much faster under the influence of culture. We then go on to describe the variety of methods by which sexuality can be studied, methods that will be applied repeatedly throughout the remainder of the book.

To do it justice, we must approach human sexuality with open minds, with respect for diversity, and with all the modes of inquiry that have been used to illuminate human nature. Approached in this way, the topic is not just another step in your college career: It is a personal voyage of discovery that will help you to enjoy the best that sexuality has to offer, and to avoid the worst. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 3 1/20/15 10:37 AM

4 chapter 1

Sexuality Is a Broader Concept than Sex The term sex has two meanings. First, it means the distinction between female and male—a distinction that, as we’ll see in later chapters, is not as clear-cut as you might imagine. Second, it means engaging in sexual behaviors. These behaviors may be very obviously sexual because they are marked by genital phenomena such as vagi- nal lubrication, penile or clitoral erection, orgasm, and so on. But they also include behaviors that do not directly involve the genitals, such as courtship, as well as behaviors such as kissing that may or may not be sexual depending on context.

The term sexuality includes sex but also goes beyond it to encompass the entire realm of human experience that is more or less closely connected with sex. It means, for example, our gendered traits—the psychological traits that differ, to a greater or lesser extent, between women and men. It means our sexual and romantic attrac- tions and relationships—who we find attractive or fall in love with, and how we establish, maintain, or dissolve sexual partnerships. It means becoming a parent (or preventing that from happening). It also includes the two-way relationship between our personal sexual identities and behaviors and social structures such as the law, religion, medicine, and politics. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Studying Sexuality Has Practical Benefits There are many possible reasons why you have chosen to take a course in human sexuality. Maybe you’re simply curious about a topic that is often treated with embar- rassment, evasion, or flippancy. Maybe you are looking for ways to improve your own sex life, or you think you have sexual problems that need to be solved. Maybe you are planning a career that requires an understanding of human sexuality.

Regardless of your specific motives, many practical benefits are to be gained from taking this course and reading this textbook. Here are some examples:

zz Improving your understanding of the structure and function of your geni- tals and those of your partners will help you give and receive more plea- sure from sex. zz Learning more about how people communicate on sexual topics will

increase your chances of forming and maintaining satisfying relationships and avoiding abusive ones. zz Learning about sexual diversity will encourage you to be more understanding of unusual sexual desires and behaviors—whether in others or in yourself. zz Educating yourself about contraception and sexually transmitted infections will lessen the chance that your sexual behavior may end up harming you or your partners. zz Becoming knowledgeable about sex will be an asset to you in your future career—most especially if you enter the medical or helping fields, but also in any career that brings you into contact with other people. zz Educating yourself about sex will enable you to educate others—including your friends and your own children, if you plan to have them. zz By learning to think critically about research, you will become a more discriminating consumer of media reports and advertising relating to sexuality.

Sexuality Has Changed over Time Most—but not all—women and men experience sexual desire and engage in sexual relationships at some point in their lives. This has likely been true across the course of sex A person’s identity as female or male, or sexual behavior. sexuality The feelings, behaviors, and identities associated with sex. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 4 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: pathwayS to underStanding 5

human history and prehistory, and it is true around the world today. But the ways in which these desires and relationships express themselves have been extraordi- narily varied. Here we sketch some of the changes that have occurred over time.

Sexuality has been influenced by evolution Humans evolved from the common ancestors of humans and nonhuman pri- mates, who lived about 7 million years ago. You might think that we could get some idea of early human sexuality by studying the sexual behavior of our clos- est relatives, the great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans), on the assumption that these animals have changed less over time than we have.

It turns out, however, that there is a great deal of sexual diversity even among these closely related species. Among chimpanzees, for example, most sexual behavior is between males and females and has the potential to lead to preg- nancy. Among bonobos, which look very similar to chimpanzees, sexual contact between individuals of the same sex is common. The function of such behavior is clearly not reproductive; rather, it serves the purposes of conflict resolution and alliance formation (Parish & de Waal, 2000). Among orangutans coercive sex—analogous to rape in humans—is common (Knott et al., 2010), but that’s not true for bonobos. Some of these species differences are described in Appendix A. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

One general characteristic of sexual behavior among our primate relatives is that more of it takes place than is strictly necessary for reproductive purposes—some- times a great deal more. Another is that individuals compete for sex partners: Males often compete for access to the most fertile females, while females often compete for the attention of high-ranking males. You don’t have to be a sex researcher to know that these kinds of competition are prevalent in our own species today. It’s likely that competition for partners has characterized sexuality throughout human history and prehistory, and that this competition has driven the evolution of sex differences in appearance and behavior.

Early in the evolution of our species, humans probably lacked understanding of the connection between coitus (penile-vaginal intercourse) and reproduction. Of course, they acted as if they understood, just as our primate relatives do, but their sexual behavior was actually driven by instincts that required little conscious aware- ness. Even today, there are human cultures where people are unaware of biological facts that seem obvious to us, such as the fact that a child has just one father, or that pregnancy and childbirth result from a single act of coitus (Box 1.1).

Over the course of human history the trend toward an increasingly conscious understanding of how sex “works” has influenced human sexuality in directions that seem counterintuitive in evolutionary terms. For example, the knowledge that the deposition of semen (the male ejaculate) in the vagina is what causes pregnancy led to the introduction of contraceptive practices. These included withdrawal of the penis prior to ejaculation—a practice known already in Old Testament times—and the use of various kinds of barriers placed in the vagina. Similarly, methods intended to interrupt an established pregnancy—by use of certain herbs or poisons, or by black magic—were widely used in the Middle Ages, with varying success. As methods for contraception and abortion have improved over the centuries, so has it become increasingly possible to enjoy the pleasures of sex without its natural consequences. This has undoubtedly increased people’s—especially women’s—willingness to engage in sex both within and outside of established relationships. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Society has changed sexuality Human sexuality has been greatly influenced by the development of social controls. The transition from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one of settled agriculture took place coitus Penile-vaginal intercourse.

Male primates, such as these golden snub-nosed monkeys, often fight over access to females.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 5 1/20/15 10:37 AM

6 chapter 1

in the Middle East roughly 10,000 years ago. This transition led eventually to the formation of city-states, which required governments and the regulation of social behavior. Nudity was restricted, in part with the aim of reducing sexual arousal, pre- venting the sight of sexual arousal in others, and eliminating sexual conflicts. (Some present-day hunter-gatherer cultures still permit nudity.) Marriage was formalized, and nonmarital sex was discouraged to a greater or lesser degree.

Meet My Dads no matter how many men a woman has sex with, any child she bears has only a single biological father—the man whose sperm fertilized the woman’s ovum. in most cultures around the world, people accept this reality of single paternity. yet anthropologists have discovered an exception among many of the indigenous tribal societies of lowland South america (amazonia and nearby areas). here people believe that a man’s semen remains in the woman’s body indefinitely after sexual intercourse, so if several different men have sex with her before she becomes pregnant, then all of them contribute to the making of her child (Becker- man & Valentine, 2002).

this belief is called partible paternity (“divisible fatherhood”). By studying language relationships among the societies where partible paternity is found, anthropologist robert walker of the university of Missouri and his colleagues have traced it back to the distant past, probably to the time when the lowlands were first settled and the settlers spoke a common language (walker et al., 2010). (Paper Human Sexuality homework help) what benefit does the concept of partible paternity confer? anthropologists such as William Crocker of the Smithsonian institution have found that the societies that believe in partible paternity engage in distinctive sexual practices (crocker & crocker, 2003). they may participate in rituals in which women engage in sex sequentially with multiple men. and unlike in other cultures, where men typically guard their wives from sexual con- tact with other males, men in these amazonian tribes may freely offer their wives to male relatives as well as to powerful men who are actual or potential allies. partible paternity, and the practices associated with them, benefit women’s efforts to raise children. that’s because the multiple “fathers” of a given child may give gifts in exchange for sex, may support or protect the child, or may at least refrain from killing the child. (the killing of infants and children by men has traditionally been a significant cause of mortality in Amazonian cultures.) what about the men? on the face of it, the notion of partible paternity seems to disadvantage them, because they may end up supporting children who are not biologically theirs. on the other hand, they are “hedging their reproductive bets” by spreading their semen widely. this may be of particular value to high-status men, who gain disproportionate access to other men’s wives, thanks to partible paternity. in addition, partible paternity gives men some assurance that their biological children will have male support in the event of their own premature death, something that’s all too common in Amazonia. this still leaves unanswered the question of why partible paternity is common in lowland South America but rare else- where. the answer may be related to the importance of kin- ship and alliances in those societies, combined with a general absence of material wealth. in such circumstances paternity may be used as a unit of wealth that can be traded, as it were, in social networks. partible paternity the belief that two or more men may be fathers of the same child.

This Araweté woman of Brazil may believe that two or more men fathered her son.

Box 1.1 Cultural Diversity

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 6 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: pathwayS to underStanding 7

Organized religion played a role in these changes (Endsjo, 2011). Although religious teachings have varied greatly, they have often fostered procreative heterosexual sex within marriage while labeling other forms of sexual expression as sinful. This was particularly true for the Christian religion: For most of the two millennia since its foundation, Christian teachings forbade all nonmarital sex, homo- sexual sex, masturbation, contraception, abortion, and polygamy. Even marital sex was restricted to coitus in certain positions, and it was forbidden on certain days of the week and during Lent (Ranke-Heinemann, 1990). Priests were commonly barred from marriage or any kind of sexual activity. This changed to some extent after the Reformation, when western Christianity splintered into numerous denominations, some of which have become much more liberal in the area of sexual ethics compared with the Catholic Church. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

The development of large-scale societies led to the emergence of class structures, with the rich and powerful at the top and the impoverished masses at the bottom. What class you belonged to greatly influenced your sex life. Take India: The Kama Sutra, compiled around the 2nd century, describes innumerable ways for men to obtain sexual pleasure and to give sexual pleasure to women (Vatsyayana, 1991) (Figure 1.1). It also describes sex between women and between men. But the Kama Sutra was written for and about the idle rich. (What to do between breakfast and lunch? Teach your parrot to talk.) If the sex lives of low- caste Indians were anything like they are today, they involved hasty, fully-clothed couplings with the minimum of pleasure or romance (Nath & Nayar, 1997).

Another way that class influenced sexuality had to do with polygamy. The major- ity of human cultures have permitted men to have more than one wife, but it was largely rich and powerful men who did so, because they had sufficient means—King Solomon is said to have had a thousand wives. Polygamy reduced the numbers of available women and thus made it harder for poor men to afford even one wife. What’s more, polygamy is connected with the idea that women are men’s property— if a rich man has many cattle, why shouldn’t he have many wives? By banning polyg- amy, the Christian religion promoted a somewhat more gender-equitable society.*

Across history, large numbers of men have been deprived of a sex life altogether by being castrated—that is, by having their testicles removed, and sometimes the penis also. Such men were called eunuchs. Castration was carried out as a punish- ment among criminals or prisoners of war, or (if done before puberty) to produce asexual male slaves who could serve certain roles such as court attendants, harem guards, dancers, or singers. Some eunuchs achieved powerful positions in imperial courts across Asia. In India, some men were (and still are) voluntarily castrated as an initiation into the transgender religious caste known as hijras, who are described further in Chapter 4 (Nanda, 1998). (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Figure 1.1 The Kama Sutra describes a wide variety of sexual positions.

* In early Islam, polygamy helped provide for the many women whose husbands died in warfare.

heterosexuality Sexual attraction to, or behavior with, persons of the opposite sex.

homosexuality Sexual attraction to, or behavior with, persons of the same sex.

polygamy Having more than one spouse at the same time, as a social institution.

castration Removal of the testicles or testicles and penis.

eunuch A man who has been castrated.

transgender (or trans) Identifying with the other sex or rejecting gender norms.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 7 1/20/15 10:37 AM

8 chapter 1

In general, castration has served the interests of noncastrated men, especially powerful men, and it therefore represents another way in which class and sexuality interact. Today, castration by surgery or “chemical castration” by drugs is performed voluntarily on some men with prostate cancer in an effort to prolong their lives—per- haps a quarter of a million American men are in this situation (Wassersug et al., 2014). (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Another important effect of cultural change has involved sexually transmitted infections. When people lived in small groups and stayed in a restricted area, they tended to reach a biological accommodation with the infectious agents (bacteria and viruses) present in that population, such that their effects were not especially severe. Increases in population density and long-distance travel changed this picture: The organism that causes syphilis, for example, was present in the native populations of the Americas long before the arrival of Columbus and other explorers, but when these men returned to Europe, bringing the organism with them, it unleashed a dev- astating epidemic (Rothschild et al., 2000). Potentially fatal diseases such as syphilis and (more recently) AIDS made sex itself seem frightening and sinful.

Marriage has been transformed Yet another important change has been the radical decline in birth rates that has taken place in most countries, starting in the late 18th century. Over this period the number of children born to the average American woman has fallen from 7 or 8 to about 2 (Figure 1.2). Today, there are plenty of women or couples who choose to have no children at all—something that used to be quite unusual, except for women in religious orders. This decline has not been accompanied by any decline in people’s interest in sex. Thus the idea has gained currency that sex has a legitimate emotional or recreational function, beyond the production of children.

The institution of marriage has changed over time (Abbott, 2011). In many tradi- tional societies marriage signified the transfer of ownership of a woman from her father to her husband; marriages were negotiated and often involved large bridal payments. People fell in love, but they were lucky if they married the people they fell in love with. In Europe and America, even as late as the 19th century, a suitor was expected to ask the girl’s father for permission to propose to her, and if permis- sion was refused—because the young man had insufficient means, for example—the young couple’s only recourse might be to run away (elope) and marry at some distant location. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

A woman was expected to be a virgin when she married, but a man could be forgiven or even admired for “sowing his wild oats.” (This was an example of the double standard, by which males and females were, and still may be, held to differ- ent moral codes.) The husband’s and wife’s roles in marriage were also quite distinct:

double standard The idea that acceptable behavior is different for men than for women.

DHS3E_0102.ai LeVay Baldwin Dragon�y Media Group 10.17.14

B ir

th s

pe r

w om

an

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

18 10

18 00

18 20

18 30

18 40

18 50

18 60

18 70

18 80

18 90

19 00

19 10

19 20

19 30

19 40

19 50

19 60

19 70

19 80

19 90

20 00

20 10

Year

White African-American

Figure 1.2 Declining birthrates This graph shows the average number of children born to American women between 1800 and 2010. The data for white and African-American women are plotted separately.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 8 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: pathwayS to underStanding 9

The husband was the breadwinner, the wife the homemaker and child rearer, perhaps with the help of servants.

Before the 20th century, marriage was for life: Divorce was quite uncommon and was only permitted in cases of proven adultery. Divorce laws were greatly liberalized over the course of the 20th century, and now nearly half of all U.S. marriages end in divorce rather than death (Wilcox & Marquardt, 2011). What’s more, it’s now widely accepted that women are sexually active before mar- riage, and that couples may live together (cohabit) before mar- riage or without marrying at all. And the birth of children outside of marriage, once a shocking secret, is now more or less routine: Over 40% of all U.S. births are now to unmarried women, who may be single or cohabiting with a man or with a woman (Martin et al., 2013).

Up until the mid-20th century the vast majority of Americans considered inter- racial marriage to be sinful, and such marriages were illegal in many states. Atti- tudes changed gradually after World War II, and in 1967 the U.S. Supreme Court established a constitutional right to marry across racial lines (Figure 1.3). Currently we are witnessing a similar trend with regard to same-sex marriage, but gay couples who marry today are joining an institution that has lost a great deal of its former significance. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Sex has become a topic of social discourse The 20th century saw a dramatic increase in people’s willingness to talk about sex. At the beginning of the century Victorian prudery still ruled: Most people could talk about sex only obliquely, if at all. Then came a series of outspoken researchers and activists whose work turned sex into a hot topic of conversation. Here are a few of them:

zz Havelock Ellis (1859–1939) was an English physician who described unusual kinds of sexual expression (which had previously been called “perversions”) in a sympathetic rather than a condemnatory way. zz Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was an Austrian neurologist and founder

of psychoanalysis. He proposed that our lives are governed by a roiling unconscious world of sexual drives and conflicts (Box 1.2). zz Margaret Sanger (1879–1966), an American social activist, campaigned

tirelessly and effectively for women’s right to learn about and practice contraception. zz Alfred Kinsey (1894–1956) was an Indiana University biologist whose pio-

neering sex surveys (the “Kinsey Reports”) caused a sensation when they were published in 1948 and 1953 (Figure 1.4). zz Margaret Mead (1901–1978) was an American cultural anthropologist who

described the sexually uninhibited lifestyles of some Pacific Islanders. zz William Masters (1915–2001) and Virginia Johnson (1925–2013), of Wash-

ington University in St. Louis, pioneered the physiological study of sexual responses in healthy people and in those with sexual disorders.

cohabitation A live-in sexual relationship between individuals who are not married to each other.

Figure 1.3 Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas and his wife Virginia are one of the many couples who have benefited from the court’s 1967 ruling that there is a constitutional right to marry across racial lines. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 9 1/20/15 10:37 AM

10 chapter 1

School sex education, which is now mandated in 22 U.S. states (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014) and throughout Canada, has also promoted discussion and awareness of sexual issues. Even today, though, many Americans find it difficult or inappropriate to talk about sex, and in some more-conservative cultures it may be completely off-limits.

Social movements have affected sexuality Political and social movements have impacted sexuality in America and elsewhere. In the 1970s and 1980s the women’s movement asserted women’s right to control their own bodies (through contraception and abortion, for example), to be free of sexual coercion, and to seek pleasure in sexual relationships. The idea gained ground that men shared responsibility for ensuring that their female partners experienced pleasure, including orgasm, during sex.

The gay liberation movement led to the increasing acceptance of homosexuality, which led in turn to the enactment of anti-discrimination laws, starting in the 1980s, and the nationwide legalization of gay sex by a 2003 ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court. Advocates have campaigned for recognition and social acceptance of many other facets of sexuality: bisexuality, asexuality, transgender identity, intersexual- ity, plural marriage (polygamy), polyamory, sadomasochism, fetishes, pedophilia, pornography, and prostitution. (If some of these terms are unfamiliar to you, don’t worry: We will be covering them all in later chapters.) Although these efforts have met with widely varying success—and rightly so, you may think—what they have done is change the conversation: Sexual expression, it’s now increasingly agreed, should be legally restricted only when it makes rational sense to do so, not simply when it runs afoul of tradition, prejudice, or good taste.

Of course, sexuality doesn’t just change over time; it also varies widely from place to place around the present-day world, and among individuals within the same population. We will focus primarily on North America, the region where this text is used, but from time to time we will make trips overseas to look at examples of global diversity in sexual behavior and ideas about sexuality.

Figure 1.4 Let’s talk about sex. Sex researcher Alfred Kinsey (far right) lectures at the University of California in 1949.

What was the “sexual revolution” of the 1960s?

It was a youth-led movement for greater sexual freedom and indi- viduality, driven by rebellion against the more orthodox World War II generation and fueled by feminism, the contraceptive pill, rock and roll, and drugs. An enduring conse- quence was the greater acceptance of sex outside of marriage. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

FAQ

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 10 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Freud and Hirschfeld: Contrasting Theories on Sexual Orientation about a century ago, two european doctors proposed radically different theories to account for why some people are sexually attracted predominantly to members of the other sex while oth- ers are attracted to members of the same sex or to both sexes— a characteristic we now call sexual orientation. in Vienna, Sig- mund Freud (Figure A) developed a theory that was based on the concept of an unconscious mind, whose operations could supposedly be probed by psychoanalytic techniques such as free association, the interpretation of dreams, and slips of the tongue. the unconscious mind, though hidden from view and free from moral restraints, nevertheless resembled the con- scious mind in many respects—both were capable of rational thought, planning, memory, and emotion.

in Freud’s conception, the unconscious mind was more broadly focused in its sexual desires than was the conscious mind. this was particularly true during early childhood, which he believed included autoerotic and homosexual phases as well as incestuous desires directed toward one or the other parent. Freud thought that the “normal” progression to adult hetero- sexuality could be derailed in various ways, often involving unconscious emotional processes such as a hostile, too-close, or jealous relationship with a parent or sibling. these phenom- ena could lead to what Freud called perversions, that is, men- tal states in which adult sexual desires were directed toward atypical targets, such as people of the same sex (homosexu- ality), inanimate objects (fetishism), and so on. or they could lead to neuroses, in which the sexual element was supposedly repressed from consciousness altogether and reemerged in the form of nonsexual traits and disorders, such as obsessive- compulsive behaviors, depression, or “hysteria.”

in Berlin, Magnus hirschfeld (Figure B) took a quite different view. hirschfeld proposed the existence of two neural centers in the brain that were responsible for sexual attraction to men and to women, respectively. he suggested that during early fetal life all humans possessed both centers, but later one center grew and dominated, while the other regressed. in men, of course, it was usually the center for attraction to women that persisted, while in women it was the center for attraction to men. only in the minority of homosexual individuals did development take the opposite course. hirschfeld believed that sex hormones (then understood in only a very rudimentary way) channeled develop- ment in one direction or another, and that people also had a genetic predisposition to same-sex or opposite-sex attraction.

in many ways, the views of Freud and hirschfeld represented opposite approaches to understanding the mind and sexual- ity. Freud tried to understand the mind in terms of processes that, though hidden, were inherently mental—unconscious thoughts. and he believed interpersonal relationships held the key to sexual orientation and other aspects of adult sexuality.

to Freud, getting to your adult sexuality was a long, sometimes chaotic drama in which the unconscious mind took the leading role. hirschfeld, on the other hand, tried to reduce the mind to relatively simple nonmental phenomena such as the growth and activity of nerve cells, hormone secretion, and information encoded in the genes. in hirschfeld’s view, these phenomena controlled sexual development in a manner that was largely independent of family relationships and other aspects of life experience. to hirschfeld, getting to your adult sexuality was a process that unfolded mechanistically without your active par- ticipation—it simply happened to you.

Freud’s theories came to dominate most people’s ideas about the mind and sexuality through the early and middle part of the 20th century, while hirschfeld’s theories languished in obscurity. toward the end of the century, however, a noticeable shift of views occurred. to some people, Freud’s theories began to seem capricious, poorly substantiated, or inspired by prejudice (against women especially). Meanwhile, scientific advances tended to bol- ster a biological view of sexuality. Studies in animals showed that prenatal hormone levels do indeed influence sexual behavior in adulthood, and family studies supported the idea that genes do have some influence on sexual orientation in humans.

probably the dominant view at present is that both approaches offer potential insights into human sexuality. there must be some biological underpinnings to our thoughts and behaviors, and exploring these underpinnings is likely to tell us a lot about why people differ from one another sexually. on the other hand, it seems likely that some aspects of human sexuality need to be studied at the level of thoughts—in other words, by a cognitive approach. thus, even if neither Freud’s nor hirschfeld’s theories turn out to be entirely correct, they may both have contributed useful styles of thinking to the discussion. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

perversion an obsolete term for atypical sexual desire or behavior, viewed as a mental disorder.

neuroses Mental disorders such as depression that, in Freudian theory, are strategies for coping with repressed sexual conflicts.

LB4E_BX0101.eps Human Sexuality 4E LeVay Baldwin Sinauer Associates 06.27.11

Box 1.2 Controversies

(A) Sigmund Freud (B) Magnus Hirschfeld (1856–1939) (1868–1935)

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 11 1/20/15 10:37 AM

12 chapter 1

Sexuality Can Be Studied with a Wide Variety of Methods Investigators trained in many different disciplines make contributions to our under- standing of human sexuality. We could fill a whole book with an account of the meth- ods that are being used to study the topic. Here, we pick out some of the key areas and highlight certain research studies that illustrate the methods that are available.

Biomedical research focuses on the underlying mechanisms of sex Biomedical research is the approach that has the greatest practical impact on people’s sex lives. Here are a few examples:

zz Hormone-based contraception and abortion zz Drug treatments for reproductive cancers zz Drug treatments for erectile disorder, premature ejaculation, and low male

sex drive (with research into drug treatments for female sexual disorders being, so far, less successful) zz Methods to prevent, cure, or effectively treat sexually transmitted infec-

tions, including AIDS zz Technologies to treat infertility in women and men zz Improvements in the safety of pregnancy and childbirth

Biomedical researchers often turn to nonhuman animals to deepen their understand- ing of human nature, including human sexuality. Animal research involves studying the structure, function, and development of bodily systems that are involved in sex and reproduction. Most of the advances listed above were made possible by research using laboratory animals. In addition, researchers study the sexual behavior of ani- mals, both in the laboratory and in the wild. Although this book is titled Discover- ing Human Sexuality, we make no apology for including a great deal of information about, or derived from, nonhuman species.

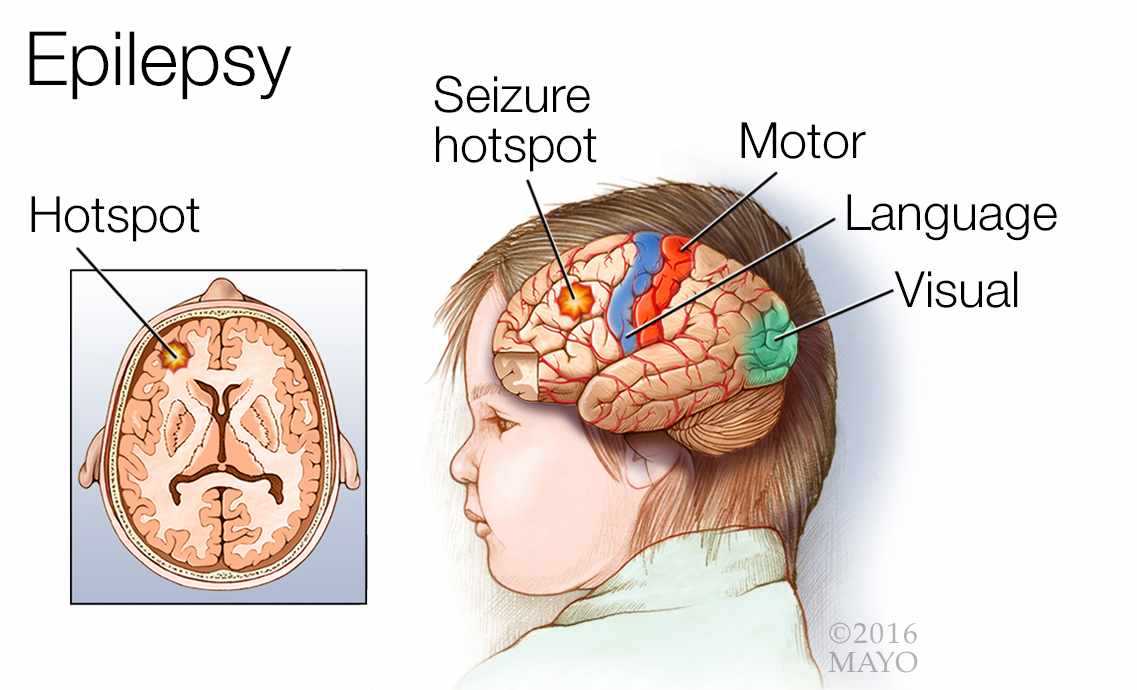

Still, the introduction of modern imaging technologies has enabled the direct study in humans of topics that earlier could only be studied in animals. This is particularly true for brain function, which can now be studied with a variety of imaging tech- niques (Figure 1.5). In addition, the decipherment of the human genome is enabling all kinds of advances, such as the ability to ascertain the sex of a fetus and to diagnose certain fetal abnormalities on the basis of a simple blood sample drawn from the mother. And as we’ll discuss in Chapter 12, current research is attempting to home in on genes that influence such important traits as a person’s sexual orientation. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

One study that exemplifies the biomedical approach to sexuality was conducted by one of this textbook’s authors (Simon LeVay) about 25 years ago (LeVay, 1991). Basing his research on earlier work on laboratory animals, LeVay hypothesized that there might be structural differences between the brains of gay (homosexual) and straight (heterosexual) people. By examining the brains of deceased individuals, he found that a part of the brain involved in sexual behavior (a small region within a part of the brain known as the hypothalamus) was larger in straight men than in gay men. Other researchers extended this line of work to living people by the use of imaging techniques, and it’s now known that there are several differences in brain organization, not only between gay and straight men, but also between lesbian and straight women, as we’ll discuss in Chapter 12. Collectively, these studies helped shift our conception of homosexuality (and heterosexuality) from something that is learned or culturally imposed to something more akin to an inborn trait.

sexual orientation The direction of an individual’s sexual feelings: sexual attraction toward persons of the opposite sex (heterosexual), the same sex (homosexual), or both sexes (bisexual).

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 12 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: pathwayS to underStanding 13

Psychology includes diverse approaches to sexuality Psychology, the study of mental processes and behavior, has splintered into numer- ous overlapping subdisciplines, each of which tends to use distinct methods. The branch of psychology most significant to the study of sexuality is social psychol- ogy—the study of how we think about, influence, and relate to other people. Social psychologists concern themselves with all kinds of sexual matters, such as sexual attraction and relationships, violence between intimate partners, and anti-gay prejudice.

Here’s one example of how social psychologists tackle an important question relat- ing to sexuality. Researchers at UCLA, led by Neil Malamuth, have been interested in the question of whether portrayals of sexual violence in the media and pornog- raphy make men more accepting of such violence, as has been asserted by many feminists. Out of a group of male college students, half were randomly assigned to watch movies that portrayed sexual violence against women—specifically, movies in which a woman was raped but subsequently fell in love with her rapist. The other students (the control group) watched movies that contained no sexual violence. A few days later the students were given a sexual attitudes questionnaire. The results supported the feminist contention: Male students who watched sexually violent mov- ies expressed significantly more accepting attitudes toward sexual violence than the men in the control group. This and other studies have convinced the UCLA research- ers that exposure to images of sexual violence really does predispose some men to commit sexual assaults against women (Malamuth et al., 2000; Hald et al., 2010). (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

psychology The study of mental processes and behavior.

social psychology The study of one’s relationship to others.

feminism The movement to secure equality for women; the study of social and psychological issues from women’s perspectives.

control group A group of subjects included in a study for comparison purposes.

Figure 1.5 Sex on the brain This shows (in red) the average pattern of activity in the brains of ten women while they were experiencing orgasm, using a technique called functional mag- netic resonance imaging (fMRI). Activity immediately prior to orgasm has been digitally sub- tracted from the image, so the image shows activity related specifically to orgasm and not to general sexual arousal. Several parts of the brain are active during orgasm, but two areas of particular interest are the amygdala and hypothalamus, both of which play important roles in the regulation of sexual feelings and behaviors. (Image courtesy of Nan Wise and Barry Komis- aruk, Rutgers University.)

DHS 3E Figure 01.05 Sinauer Associates 11/6/14

Left hypothalamus

Right amygdala

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 13 1/20/15 10:37 AM

14 chapter 1

Cognitive psychology is the study of internal mental processes. As an example, there’s a well-known stereotype that gay men are “like women” and lesbians are “like men.” How true is this? To find out, cognitive psychologists have conducted many studies comparing a variety of mental traits, skills, and attitudes in gay and straight people. Researchers at the University of Haifa, in Israel, for instance, picked empathy, which is the ability to detect and feel the emotions of other people. This trait is typically better developed in women than in men. Consistent with the stereotype, the researchers found that gay men scored higher on tests of empathy than straight men, whereas lesbians scored lower than straight women (Perry et al., 2013). Still, looking at the entire body of research in this field, gay people show a patchwork of gender-typical and gender-atypical traits, and what’s true on average is not necessar- ily true about individuals (LeVay, 2011). We review this topic further in Chapter 12.

Evolutionary psychology seeks to explain how evolution has molded our genetic endowment to favor certain patterns of sexual feelings and behaviors. One idea in evolutionary psychology is that because reproduction is so much more demanding for females than for males, genes have evolved that cause females to be very picky in their choice of sex partners. As a result, other genes have evolved that cause males to engage in competitive and risky sexual displays—displays that are intended to influence females’ choices.

It’s well established that men are more likely than women to engage in risky behaviors, but it’s not clear whether the risks we take in everyday life—such as when we cross a busy street—are actually sexual displays. To help answer this question, an international group of evolutionary psychologists descended on Britain’s University of Liverpool (Pawlowski et al., 2008). They stationed themselves near the campus’s busiest crosswalk, and over a period of 3 months they observed how 1000 men and women crossed the street (Figure 1.6). Specifically, they noted how much risk the stu- dents took in crossing (i.e., whether they crossed when vehicles were approaching) and who else was present when each person crossed. As might have been expected, the researchers found that men took more risks than women. The interesting finding, though, was that the presence of women nearby significantly increased the likelihood that a man would attempt a risky crossing, whereas the presence of men nearby did not influence his decision one way or another. Women, on the other hand, paid little or no attention to who was present, regardless of their sex, when they decided whether to cross. The researchers concluded that even a mundane act such as crossing a street can be motivated in part by the urge to engage in sexual displays—but only for men in the presence of women. Women do engage in sexual dis- plays—when they flirt, for example—but these displays don’t commonly take the form of risk-taking behavior.

Another area of psychology is concerned with ethnic and cultural diversity in sexual attitudes, behavior, and relationships. This kind of research, which is conducted primarily by cultural anthropologists, involves field- work of the kind pioneered by Margaret Mead and oth- ers. An example is the research into the concept of parti- ble paternity in Amazonia that was discussed in Box 1.1. Another example closer to home concerns the Native American tradition of “two-spirit” people—individuals who incorporate both a male and a female identity and who are accorded a special role in their communities. These people have been studied in detail by anthropology

Figure 1.6 Looking for love? Crossing the street in front of traffic can be a form of sexual display, according to research at the University of Liverpool. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

cognitive psychology The study of the information-processing systems of the mind.

evolutionary psychology The study of the influence of evolution on mental processes or behavior.

cultural anthropology The study of cultural variations across the human race.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 14 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: pathwayS to underStanding 15

gist Walter Williams, who spent a great deal of time living among Native Americans (Williams, 1986). The study of two-spirit people challenges assumptions about gen- der that are prevalent in most Western societies (Sheppard & Mayo, 2013).

Sociologists focus on the connection between sex and society Sociology is the scientific study of society. Sociologists make a unique contribution to the study of human sexuality by linking the sexual behaviors and attitudes of indi- viduals to larger social structures. Sociologists examine how sexual expression varies with age, race, national origin, religious and political beliefs, place of residence, edu- cational level, and so on. Such studies are often carried out by means of sex surveys.

We already briefly mentioned the surveys conducted by Alfred Kinsey in the mid- 20th century. With the onset of the AIDS epidemic around 1980, the need for detailed information about sexual practices and attitudes spurred a host of new sex surveys. Most notable among the surveys was one conducted by sociologists at the University of Chicago and elsewhere—the National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS) (Laumann et al., 1994). A comparable British survey—the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NSSAL)—was published in the same year (Wellings et al., 1994) and has been repeated twice, most recently in 2013 (Mercer et al., 2013). Besides being more up-to-date than the Kinsey surveys, the NHSLS and NSSAL were technically superior in a number of respects, especially in their use of modern random-sampling methods and advanced techniques of statistical analysis, made possible by computers.

One interesting finding of the NHSLS concerned masturbation. This practice is often thought of as something a person does as a substitute for “real” sex when part- ners are unavailable. No doubt this is sometimes the case, but the survey findings indicate that people usually masturbate in addition to engaging in partnered sex, not as a substitute for it. In fact, women with partners masturbate more than women without them, according to the survey.

In 2010, researchers at the Center for Sexual Health Promotion at Indiana Univer- sity published findings from a new National Survey of Sexual Health and Behav- ior (NSSHB) (Reece et al., 2010b). This survey obtained responses from nearly 6000 Americans age 14 to 94. Among the findings was a gender gap in the experience of heterosexual sex: More men than women experienced orgasm during their most recent act of penile-vaginal intercourse, whereas more women than men experienced pain.

Another valuable source of information is the General Social Survey (GSS), which is run by sociologists at the University of Chicago. The GSS has been asking Americans pretty much the same questions at 1- or 2-year intervals since 1972. Using the GSS survey data it is possible to find out how people’s attitudes toward, say, sex between unmarried couples, has changed over time. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

From time to time throughout this book, we cite findings from these and other surveys. We also occasionally refer to magazine-sponsored surveys, which tend to cover intimate topics that the official surveys ignore. In 2012, for example, Esquire magazine commissioned a national random-sample survey that came up with all kinds of interesting information about current U.S. sex practices—such as that het- erosexual men’s favorite sexual position is the “cowgirl” (the woman straddling the man and facing forward) (Esquire, 2012).

Sex surveys are plagued with a variety of problems. It is often difficult to obtain truly representative samples of respondents. In addition, respondents may be reluctant to divulge details of their sex lives, especially if the information could be regarded as shameful. Kinsey tried to overcome this problem by the use of leading questions (“When did you first . . . ?” rather than “Have you ever . . . ?”). In more recent surveys researchers have attempted to reduce the embarrassment factor by

gender The collection of psychological traits that differ between males and females.

sociology The scientific study of society.

National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS) A national survey of sexual behavior, relationships, and attitudes in the United States, conducted in the early 1990s.

National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NSSAL) A periodic British survey of sexual behavior, relationships, and attitudes, most recently conducted in 2013.

National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) A national survey of sexual behavior in the United States, based at Indiana University and published in 2010.

General Social Survey (GSS) A long-running periodic survey of the U.S. population run by the National Opinion Research Center.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 15 1/20/15 10:37 AM

16 chapter 1

allowing interviewees to type their responses directly into a computer.

Random-sample surveys, even very large ones, are likely to encompass very few if any individuals who belong to “minorities within minorities,” such as Asian-American lesbians. Yet it is often these neglected groups about whom information is most needed. What’s more, when only a small percentage of the subjects belong to a certain group, their truthful responses may be swamped by frivolous responses from others. This apparently happened with a survey of U.S. adolescents called the National Longitudinal Study of Ado- lescent Health, or AddHealth: In this survey an improbably large number of students described themselves as gay, and they sometimes added other unlikely facts such as having artificial limbs or numerous children. The deception came to light in a repeat survey carried out on the same individuals when they were adults: By then the artificial limbs, the chil- dren, and the homosexuality had largely vanished (Savin- Williams & Joyner, 2013).

Sociologists are also interested in the mechanisms by which social structures (rang- ing from the family to the mass media) mold individual feelings and behaviors. One influential idea is that society gives us “scripts”—ways of presenting ourselves to others as we deal with social interactions. We can select from many different scripts and ad-lib on them too. This idea has been referred to as script theory (Reiss, 1986; Simon & Gagnon, 1986; Frith, 2009). (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

Here’s an example of the application of script theory to a sexual topic: Angela Bartoli and Diane Clark of Shippensburg University studied the dating scripts typi- cally used by college students. They found that men’s scripts were far more likely to involve an expectation of sex, whereas women’s scripts typically included a respon- sibility for setting limits on sexual interactions (Bartoli & Clark, 2006). This is, of course, consistent with traditional views about men’s and women’s roles in sexual negotiations. Bartoli and Clark’s finding suggest that several decades of “women’s lib” did not change this dynamic in any significant way.

Sociologists may also engage in ethnographic fieldwork, immersing themselves in their subjects’ lives in the same way that cultural anthropologists do. For exam- ple, Staci Newmahr, then a graduate student in sociology at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo, wanted to explore the lives and motivations of people who engaged in BDSM activities (Newmahr, 2011). (“BDSM” means the infliction or receipt of pain, humiliation, and the like as a sexual or recreational outlet.) To do so, Newmahr joined a BDSM club and submitted to treatments that you might consider extreme, or at least well beyond the usual requirements for a PhD. We report on some of her findings in Chapter 13.

The economic approach weighs costs and benefits How much is sex “worth?” Sometimes, as in the case of prostitution, the answer to this question can be expressed in dollar terms. But even when money doesn’t change hands, people calculate—consciously or unconsciously—the costs and benefits of sexual encounters and sexual relationships (Baumeister & Vohs, 2004). The cost may be counted not in money but in time lost from studies or career, or in the effect of a damaged reputation that lowers a person’s future value in the sexual marketplace. The benefit may not be sexual pleasure, but a secure relationship. Researchers will- ing to take a hard-nosed economic approach to these issues help us understand how much more there is to human sexuality than simple romance or “the joy of sex.”

script theory The analysis of sexual and other behaviors as the enactment of socially instilled roles.

ethnography The study of a cultural group, often by means of extended individual fieldwork.

Participants in sex surveys give more honest responses when they can do so without the presence of investigators.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 16 1/20/15 10:37 AM

Sexuality: pathwayS to underStanding 17

As an example of this approach, let’s take a look at a study that focused on how the sex ratio (the ratio of males to females in a given population) influences sexual negotiations. A basic tenet of economic theory is that the value of scarce resources tends to rise, so if one sex is in a minority, mem- bers of that sex gain leverage in the heterosexual marketplace. Because males are typically more interested in uncommitted sex than are women, it might be expected that casual sex would be more common in popula- tions with an excess of females and less common where males are in the majority. Psychologist Nigel Barber tested this prediction by obtaining data on sex ratios and teen birthrates (a proxy indicator of uncommitted sex) in 185 countries (Barber, 2000). Sure enough, teen births were highest in countries with an excess of females, and the association was not a weak one: Nearly 40% of the variability in teen birthrates between countries could be explained by their sex ratios. In later chapters we’ll see how sex ratios impact the sex lives of Americans. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

It’s worth emphasizing that individual researchers often cross the boundaries between the various disciplines just described, or collaborate with researchers from other backgrounds. Psychologists and neurosci- entists often work together, for example. This kind of boundary cross- ing has greatly enhanced researchers’ ability to understand the roots of sexual behavior and sexual diversity.

As we have seen, women and men in a variety of academic disciplines and walks of life have made important contributions to our understand- ing of human sexuality. Increasingly, however, there is a perception that sex research, or sexology, is an academic discipline in its own right. This discipline is an unusual one in that it demands training that crosses most of the traditionally established intellectual boundaries.

A variety of factors make sex research especially challenging:

zz It can be difficult to obtain appropriate subjects to study. It’s easy enough to corral a classful of human sexuality students, but how representative are these of the general citizenry, let alone humanity as a whole? zz It can be difficult to phrase survey questions in ways that encourage honest responses and that don’t bias responses to conform to researchers’ preconceptions. zz It can be difficult to extrapolate from animal research to human subjects. zz It can be difficult to obtain funding for research: Conservative politicians

have taken to vetting grant applications, looking for proposals that they can ridicule or defund. On the other hand, the epidemics of AIDS, herpes, and other sexually transmitted infections have led to the investment of a great deal of public and private funds into sex-related research topics.

Numerous organizations at local, international, and global levels now foster sex research. In the United States, the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality (SSSS, or “Quad-S”) publishes the Journal of Sex Research and other periodicals. The Ameri- can Association of Sexuality Educators Counselors and Therapists (AASECT) and the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (SSTAR) certify educational programs in sex education and therapy. There are also institutes devoted to research or training in issues of sexuality, such as the Kinsey Institute (which is affiliated with Indiana Uni- versity), and special-purpose organizations such as the Guttmacher Institute (which focuses on family planning issues). (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)

At an international level, two organizations stand out. The International Academy of Sex Research publishes the Archives of Sexual Behavior. The World Association for Sexual Health, which represents sex-research and sexual-health organizations from

Prostitution is not the only sphere in which people calculate the value of sex and sexual relationships.

sexology The scientific study of sex and sexual disorders.

01_DHS3E_CH 01.indd 17 1/20/15 10:37 AM

18 chapter 1

53 countries, issued a universal Declaration of Sexual Rights in 1997, and it has been updated since that time. The 2014 declaration (in abridged form) is as follows:

zz The right to equality and non-discrimination zz The right to life, liberty, and security of the person zz The right to autonomy and bodily integrity zz The right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or

punishment zz The right to be free from all forms of violence and coercion zz The right to privacy zz The right to the highest attainable standard of health, including sexual health; with the possibility of pleasurable, satisfying, and safe sexual experiences zz The right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its application zz The right to information zz The right to education and the right to comprehensive sexuality education zz The right to enter, form, and dissolve marriage and other similar types of relationships based on equality and full and free consent zz The right to decide whether to have children, the number and spacing of children, and to have the information and the means to do so zz The right to the freedom of thought, opinion, and expression zz The right to freedom of association and peaceful assembly zz The right to participation in public and political life zz The right to access to justice, remedies, and redress

Summary zz Sexuality has changed over time, under the influence of evolution and culture. Certain modes of sexual behav- ior, such as competition for sex partners, were inherited from our nonhuman ancestors. The increasing conscious understanding of the connection between sex and repro- duction led to the development of efforts to interrupt the connection—by contraception and abortion. (Paper Human Sexuality homework help)