Nursing Paper Example on Septicemia

Nursing Paper Example on Septicemia

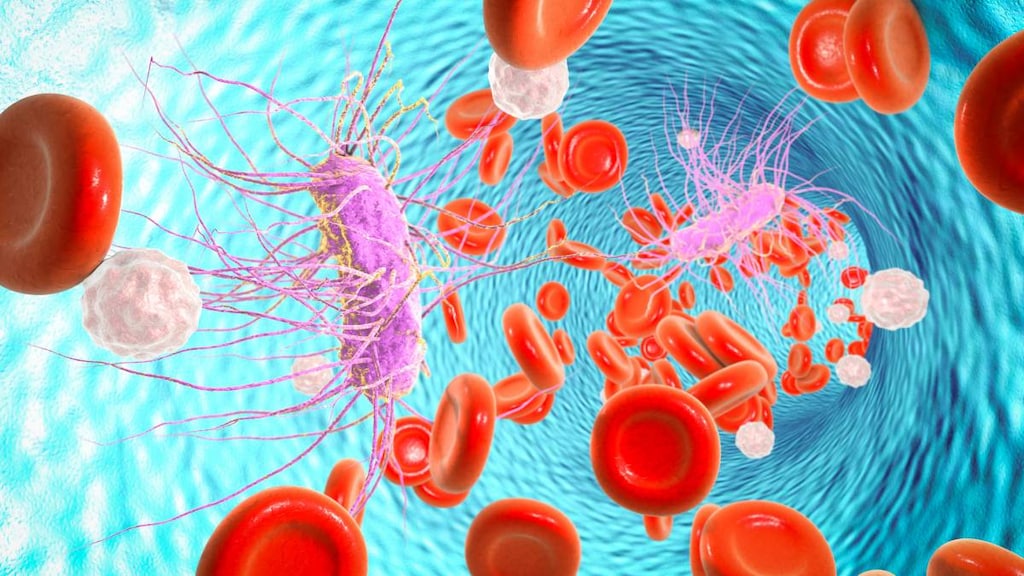

Septicemia, commonly referred to as “blood poisoning,” is a serious bloodstream infection that can progress rapidly and lead to severe systemic inflammation and multiple organ failure if untreated. This condition occurs when a pathogen, typically bacteria, enters the bloodstream and triggers an overwhelming immune response. Septicemia is a medical emergency and is a precursor to sepsis when the infection leads to widespread inflammation and organ dysfunction.

Causes of Septicemia

Septicemia arises from various types of infections that spread into the bloodstream. Common sources include:

- Respiratory Tract Infections: Bacterial pneumonia is a frequent cause, especially in vulnerable populations such as the elderly.

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): UTIs, especially those caused by E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria, can lead to septicemia.

- Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: Infections from cuts, wounds, surgical sites, and abscesses can spread to the bloodstream.

- Abdominal Infections: Intra-abdominal abscesses, perforations, and infections such as appendicitis and cholecystitis are also major causes.

- Medical Devices and Procedures: Central lines, catheters, and other invasive devices pose a risk of introducing bacteria into the bloodstream, leading to septicemia (Vincent et al., 2019).

Signs and Symptoms

Recognizing septicemia is essential, as symptoms often escalate quickly and may include:

- High fever and chills: Often accompanied by sweating and an increased heart rate.

- Rapid breathing: Shortness of breath as the body responds to inflammation and low oxygen levels.

- Mental confusion: Disorientation or confusion is common, particularly as blood pressure drops.

- Skin Changes: Red streaks, rashes, or petechiae may appear on the skin.

- Hypotension: Blood pressure often falls as the infection progresses, leading to shock.

These symptoms typically worsen quickly, requiring prompt medical intervention to prevent the progression to severe sepsis or septic shock (Singer et al., 2016).

Etiology

The primary cause of septicemia is bacteremia, the presence of bacteria in the bloodstream, although fungi, viruses, and parasites can also lead to the condition. Contributing factors include:

- Immunosuppression: Individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, cancer, or diabetes, have higher risks.

- Age: Infants, older adults, and those with underlying health conditions are more susceptible.

- Chronic Illnesses: Conditions like kidney disease, liver disease, and cardiovascular conditions increase susceptibility.

- Invasive Procedures: Surgery, catheterization, and central venous access raise the risk of bloodstream infections.

- Hospitalization: Patients in hospitals, particularly in intensive care, are at higher risk due to their exposure to pathogens and medical devices (Rello et al., 2018).

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of septicemia involves a complex host response to the pathogen. Key processes include:

- Systemic Inflammatory Response: When pathogens enter the bloodstream, they trigger a strong immune reaction, releasing cytokines and other pro-inflammatory molecules.

- Endothelial Dysfunction: Inflammatory mediators damage blood vessels, increasing vascular permeability and leading to fluid leakage, tissue edema, and reduced blood flow.

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): Septicemia often leads to a coagulation cascade, causing clot formation throughout the body. This can result in microvascular clots, tissue ischemia, and multi-organ dysfunction.

- Organ Dysfunction: As the infection spreads and inflammation intensifies, oxygen delivery to organs is compromised, potentially leading to kidney failure, respiratory distress, liver dysfunction, and other complications (Hotchkiss et al., 2016).

Diagnosis

Diagnosing septicemia involves clinical examination and laboratory tests, including:

- Blood Cultures: Blood cultures are essential for identifying the causative pathogen and determining antibiotic susceptibility.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): A high or low white blood cell count is common in septicemia and indicates infection.

- Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Elevated procalcitonin and CRP levels are biomarkers indicating a bacterial infection and inflammatory response.

- Imaging: Ultrasound, X-rays, or CT scans may identify infection sources such as abscesses or organ infections.

- Organ Function Tests: Kidney and liver function tests assess the extent of organ dysfunction due to septicemia (Shankar-Hari et al., 2016).

Early and accurate diagnosis is critical in initiating appropriate therapy and improving patient outcomes.

Treatment Regimens

Treatment for septicemia requires immediate intervention to control infection and prevent organ failure:

- Antibiotics: Empirical, broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered immediately, followed by tailored antibiotics based on blood culture results.

- Intravenous Fluids: Fluid resuscitation is essential for restoring blood volume and preventing hypotension.

- Vasopressors: In cases of persistent low blood pressure, vasopressors such as norepinephrine help maintain adequate circulation.

- Organ Support: Mechanical ventilation for respiratory support, dialysis for renal failure, and other supportive measures are often needed in severe cases.

- Corticosteroids: Low-dose corticosteroids may be used in cases of septic shock to stabilize blood pressure and reduce inflammation (Rhodes et al., 2017).

Patient Education

Patient education is crucial for preventing septicemia and supporting recovery:

- Infection Prevention: Emphasizing good hygiene, wound care, and vaccination can prevent infections that lead to septicemia.

- Early Symptom Recognition: Educating patients and caregivers on early signs of infection and septicemia encourages timely medical intervention.

- Post-Septicemia Care: Many survivors experience long-term effects, including fatigue, cognitive impairment, and chronic pain. Patients should be informed about post-septicemia symptoms and advised to seek follow-up care.

- Lifestyle Adjustments: A healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet, regular exercise, and avoiding smoking, supports immune function and reduces infection risks (Prescott & Angus, 2018).

Conclusion

Septicemia is a severe and potentially fatal bloodstream infection requiring rapid diagnosis, aggressive treatment, and preventive education. Understanding the causes, pathophysiology, symptoms, and treatment strategies helps healthcare providers manage this complex condition effectively, improving patient outcomes and reducing complications.

References

Hotchkiss, R. S., Moldawer, L. L., Opal, S. M., Reinhart, K., Turnbull, I. R., & Vincent, J. L. (2016). Sepsis and septic shock. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(1), 1-21. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrdp201622

Prescott, H. C., & Angus, D. C. (2018). Enhancing recovery from sepsis: A review. JAMA, 319(1), 62-75. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2666320

Rello, J., Valenzuela-Sánchez, F., Ruiz-Rodriguez, M., & Moyano, S. (2018). Sepsis: A review of advances in management. Advances in Therapy, 34(11), 2393-2411. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12325-018-0649-3

Rhodes, A., Evans, L. E., Alhazzani, W., Levy, M. M., Antonelli, M., Ferrer, R., … & Dellinger, R. P. (2017). Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Medicine, 43(3), 304-377. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

Shankar-Hari, M., Phillips, G. S., Levy, M. L., Seymour, C. W., Liu, V. X., Deutschman, C. S., … & Angus, D. C. (2016). Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, 315(8), 775-787. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2492881

Singer, M., Deutschman, C. S., Seymour, C. W., Shankar-Hari, M., Annane, D., Bauer, M., … & Angus, D. C. (2016). The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, 315(8), 801-810. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2492881