Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective

Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective

Bell’s Palsy stands as a testament to the intricate workings of the human nervous system. This disorder, characterized by sudden facial paralysis, presents a unique set of challenges for both patients and healthcare professionals. While the exact cause remains a subject of debate, it is often associated with viral infections, particularly the herpes simplex virus. The onset of Bell’s Palsy is marked by a sudden onset of symptoms, including facial drooping and difficulty in performing basic facial movements. Despite its transient nature, Bell’s Palsy can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life, affecting their ability to communicate and express emotions. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of this disorder, its diagnosis, treatment modalities, and the importance of patient education are essential steps towards effective management and recovery. In this paper, we delve into the multifaceted aspects of Bell’s Palsy, exploring its causes, symptoms, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment regimens, and the significance of patient education in navigating this neurological enigma. (Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective)

Causes of Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s Palsy, although often shrouded in mystery, is thought to stem from a complex interplay of factors, with viral infections emerging as a prominent culprit. Among these infections, the herpes simplex virus (HSV) takes center stage, particularly in cases where individuals have been previously exposed to it. The exact mechanism by which HSV triggers Bell’s Palsy remains elusive, but it is believed to involve the virus’s ability to lie dormant within cranial nerves, including the facial nerve.

Additionally, other viral pathogens, such as the varicella-zoster virus (which causes chickenpox and shingles) and the Epstein-Barr virus (associated with mononucleosis), have also been implicated in some cases of Bell’s Palsy. These viruses, like HSV, have the potential to cause inflammation and damage to the facial nerve, leading to the characteristic paralysis observed in Bell’s Palsy.

Beyond viral infections, inflammation of the facial nerve due to various factors can contribute to the development of Bell’s Palsy. Autoimmune reactions, where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its tissues, may target the facial nerve, resulting in dysfunction and subsequent facial paralysis.

Furthermore, certain risk factors may predispose individuals to Bell’s Palsy, although their exact role in its development remains under investigation. These factors include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, pregnancy, and a history of upper respiratory tract infections. While the precise mechanisms linking these risk factors to Bell’s Palsy are not fully understood, they likely involve compromised immune function and increased susceptibility to viral infections.

Moreover, genetic predisposition may also play a role in some cases of Bell’s Palsy, although the extent of its influence remains uncertain. Studies have suggested a potential familial clustering of the disorder, indicating that certain genetic factors may contribute to an individual’s susceptibility to developing Bell’s Palsy when exposed to triggering factors such as viral infections.

In summary, the causes of Bell’s Palsy are multifaceted, involving a complex interplay of viral infections, inflammation, autoimmune reactions, genetic predisposition, and various risk factors. While much remains to be elucidated about the precise mechanisms underlying this condition, ongoing research continues to shed light on its pathogenesis, paving the way for improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. (Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective)

Signs and Symptoms of Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s Palsy manifests with distinct signs and symptoms, primarily centered around unilateral facial weakness and paralysis. The onset of symptoms is typically sudden, catching individuals off guard and often causing considerable distress.

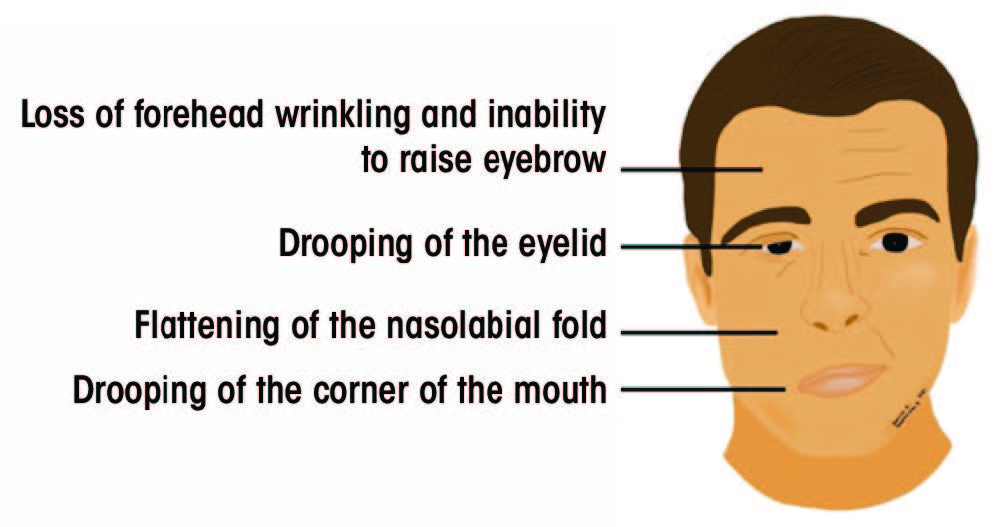

Facial asymmetry represents one of the hallmark features of Bell’s Palsy. Patients may notice a drooping or sagging appearance on one side of the face, affecting their ability to smile symmetrically or close one eye fully. This asymmetry can be particularly pronounced during attempts to perform facial movements, such as raising the eyebrows or puffing out the cheeks.

Difficulty in performing basic facial functions underscores the impact of Bell’s Palsy on everyday activities. Affected individuals may struggle with tasks as simple as speaking clearly or eating, as the muscles responsible for these actions become weakened or paralyzed on the affected side.

Moreover, Bell’s Palsy can disrupt the normal functioning of facial muscles involved in eye closure, leading to several ocular symptoms. Patients may experience dryness and irritation of the affected eye due to inadequate blinking, increasing their susceptibility to corneal abrasions and other ocular complications. Additionally, involuntary twitching or spasms of facial muscles, known as facial myokymia, may occur in some cases, further adding to the array of symptoms experienced by individuals with Bell’s Palsy.

Sensory disturbances, although less common, can also accompany Bell’s Palsy, affecting the perception of taste and sound on the affected side of the face. Patients may report alterations in taste perception, such as a metallic or bitter taste, or heightened sensitivity to loud noises (hyperacusis) due to dysfunction of the facial nerve’s sensory branches.

Furthermore, Bell’s Palsy can have significant psychosocial ramifications, impacting an individual’s self-image and emotional well-being. The sudden onset of facial paralysis may lead to feelings of embarrassment, self-consciousness, or depression, particularly in cases where the facial asymmetry is pronounced and affects facial expression.

Overall, the signs and symptoms of Bell’s Palsy encompass a spectrum of facial manifestations, ranging from weakness and asymmetry to ocular and sensory disturbances, highlighting the diverse impact of this neurological disorder on patients’ daily lives. Recognizing these manifestations is crucial for prompt diagnosis and appropriate management, ensuring optimal outcomes for individuals affected by Bell’s Palsy. (Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective)

Etiology of Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s Palsy is believed to arise from a combination of genetic predisposition, viral infections, and inflammatory processes. While the exact etiology remains elusive in many cases, several factors have been implicated in the development of this neurological disorder.

Viral infections, particularly those caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), stand out as significant contributors to the etiology of Bell’s Palsy. HSV, known for its ability to establish latent infections within sensory ganglia, including the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve, is believed to play a central role in triggering inflammatory responses and nerve damage. The reactivation of latent HSV within the facial nerve is thought to lead to nerve edema, inflammation, and subsequent compression within the narrow confines of the facial canal, resulting in the characteristic facial paralysis observed in Bell’s Palsy.

In addition to HSV, other viral pathogens, such as the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), have also been implicated in the etiology of Bell’s Palsy. These viruses, like HSV, have the potential to cause inflammatory responses and nerve damage, although their specific mechanisms of action within the facial nerve remain to be fully elucidated.

Furthermore, inflammatory processes, both infectious and non-infectious, are believed to contribute to the etiology of Bell’s Palsy. Autoimmune reactions, where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its tissues, may target the facial nerve, leading to nerve dysfunction and subsequent paralysis. Inflammatory conditions affecting adjacent structures, such as the middle ear or parotid gland, may also exert pressure on the facial nerve, compromising its function and contributing to the development of Bell’s Palsy.

While genetic predisposition has been suggested as a potential factor in some cases of Bell’s Palsy, the precise genetic mechanisms underlying the disorder remain poorly understood. Studies have identified certain genetic polymorphisms associated with an increased susceptibility to developing Bell’s Palsy, highlighting the complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors in its etiology.

The etiology of Bell’s Palsy is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, viral infections, and inflammatory processes. Further research is needed to unravel the precise mechanisms underlying the disorder and to develop targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating its impact on affected individuals. (Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective)

Pathophysiology of Bell’s Palsy

The pathophysiology of Bell’s Palsy involves a cascade of events that ultimately lead to dysfunction and paralysis of the facial nerve. While the exact sequence of these events remains incompletely understood, several key processes have been implicated in the development of this neurological disorder.

One of the primary mechanisms underlying Bell’s Palsy is inflammation of the facial nerve, triggered by various factors such as viral infections or autoimmune reactions. Inflammatory mediators infiltrate the nerve, leading to edema, or swelling, which compromises nerve function by disrupting the normal transmission of signals along its fibers. This inflammation may also cause compression of the facial nerve within the narrow confines of the facial canal, further exacerbating nerve dysfunction.

The geniculate ganglion, a sensory ganglion located within the facial nerve’s course, plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of Bell’s Palsy. Viral infections, particularly those caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), can establish latent infections within the geniculate ganglion, leading to reactivation and subsequent inflammation of the facial nerve. This inflammation affects the nerve’s motor fibers, impairing its ability to control facial muscles and resulting in paralysis.

Moreover, ischemia, or reduced blood flow, may contribute to the pathophysiology of Bell’s Palsy by depriving the facial nerve of oxygen and nutrients essential for its normal function. Ischemia can result from various factors, including vascular compression or inflammatory processes that disrupt blood supply to the nerve.

Additionally, the facial nerve’s vulnerability to damage within the narrow confines of the facial canal makes it susceptible to compression and mechanical injury. Inflammatory processes, such as those associated with viral infections or autoimmune reactions, may exacerbate this vulnerability, leading to nerve compression and subsequent paralysis.

The pathophysiology of Bell’s Palsy involves a complex interplay of inflammatory processes, viral infections, ischemia, and mechanical factors that ultimately lead to dysfunction and paralysis of the facial nerve. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying these processes and to develop targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring normal nerve function in individuals affected by Bell’s Palsy

DSM-5 Diagnosis of Bell’s Palsy

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), provides a structured approach for diagnosing Bell’s Palsy based on specific criteria. While Bell’s Palsy primarily affects the neurological system, its diagnosis involves ruling out other potential causes of facial paralysis through a comprehensive clinical assessment.

According to the DSM-5 criteria, the diagnosis of Bell’s Palsy is primarily clinical and requires the presence of unilateral facial weakness or paralysis that cannot be attributed to other identifiable causes, such as stroke, trauma, or tumors. This facial weakness typically manifests suddenly and is accompanied by other characteristic symptoms, such as difficulty closing one eye, drooping of the mouth, or asymmetry of facial expressions.

Furthermore, the DSM-5 emphasizes the importance of excluding alternative explanations for the observed symptoms through a thorough medical history, physical examination, and, in some cases, additional diagnostic tests. These tests may include imaging studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans, to rule out structural abnormalities or other neurological conditions that may mimic Bell’s Palsy.

Moreover, the DSM-5 highlights the transient nature of Bell’s Palsy, with symptoms typically reaching their peak within 48 hours of onset and gradually improving over several weeks to months. This characteristic temporal pattern, along with the absence of other neurological deficits, helps distinguish Bell’s Palsy from other causes of facial paralysis.

The DSM-5 diagnosis of Bell’s Palsy involves the presence of unilateral facial weakness or paralysis that cannot be attributed to other identifiable causes, along with a characteristic temporal pattern of symptom onset and resolution. By adhering to these diagnostic criteria and conducting a comprehensive clinical assessment, healthcare professionals can accurately identify and differentiate Bell’s Palsy from other conditions presenting with similar symptoms, facilitating timely management and intervention. (Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective)

Treatment Regimens and Patient Education

Effective management of Bell’s Palsy involves a multifaceted approach encompassing pharmacological interventions, supportive care, and patient education. By addressing both the acute symptoms and long-term implications of the condition, healthcare professionals can optimize outcomes and empower patients in their journey toward recovery.

Pharmacological interventions form the cornerstone of treatment for Bell’s Palsy, with corticosteroids and antiviral medications playing pivotal roles in reducing inflammation and combating viral infections, respectively. Oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are commonly prescribed within the first 72 hours of symptom onset to hasten recovery and minimize facial nerve damage. These medications help alleviate inflammation, thereby mitigating nerve compression and facilitating neural recovery. Similarly, antiviral agents, such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may be prescribed to target viral pathogens implicated in Bell’s Palsy, particularly herpes simplex virus (HSV). By inhibiting viral replication, antiviral medications can attenuate the severity and duration of symptoms, hastening the resolution of facial paralysis.

In addition to pharmacotherapy, supportive care plays a crucial role in managing Bell’s Palsy and mitigating its impact on patients’ daily lives. Symptomatic relief measures, such as eye lubrication and protection, are essential to prevent ocular complications associated with incomplete eyelid closure and reduced tear production. Patients are often advised to use artificial tears and wear protective eyewear, especially during sleep, to maintain ocular hydration and prevent corneal abrasions. Furthermore, physical therapy modalities, such as facial exercises and massage, may help improve facial muscle strength and coordination, facilitating the restoration of normal facial movements and expressions.

Patient education serves as a cornerstone of Bell’s Palsy management, empowering individuals to actively participate in their care and navigate the challenges associated with the condition. Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in educating patients about the nature of Bell’s Palsy, its expected course, and the importance of adherence to treatment regimens. Patients are encouraged to adhere to prescribed medications, follow-up appointments, and recommended lifestyle modifications to optimize treatment outcomes and minimize complications. Moreover, patients receive guidance on self-care strategies, such as eye protection and facial exercises, to enhance symptom management and facilitate recovery.

Furthermore, patient education extends beyond the acute phase of Bell’s Palsy to address potential long-term sequelae and psychosocial implications. Healthcare professionals provide information on potential complications, such as residual facial weakness or synkinesis, and strategies for coping with emotional challenges, such as self-image concerns and social stigma. By fostering open communication and providing ongoing support, healthcare professionals empower patients to navigate the physical, emotional, and social aspects of Bell’s Palsy, promoting resilience and facilitating successful recovery. (Nursing paper Example on Understanding Bell’s Palsy: A Neurological Perspective)