Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which the tissue lining the esophagus changes due to prolonged exposure to stomach acid. This condition is significant because it serves as a precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma, a type of cancer with a poor prognosis. Understanding Barrett’s esophagus is essential for early detection and intervention to prevent the progression of cancer. Despite its importance, many individuals may not be familiar with this condition and its implications. Therefore, this essay aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Barrett’s esophagus, covering its causes, signs and symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, DSM-5 diagnosis, treatment regimens, patient education, and concluding with the importance of awareness and proactive management. By shedding light on this condition, individuals can better recognize its symptoms, seek appropriate medical attention, and take proactive steps to manage their health effectively. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Causes

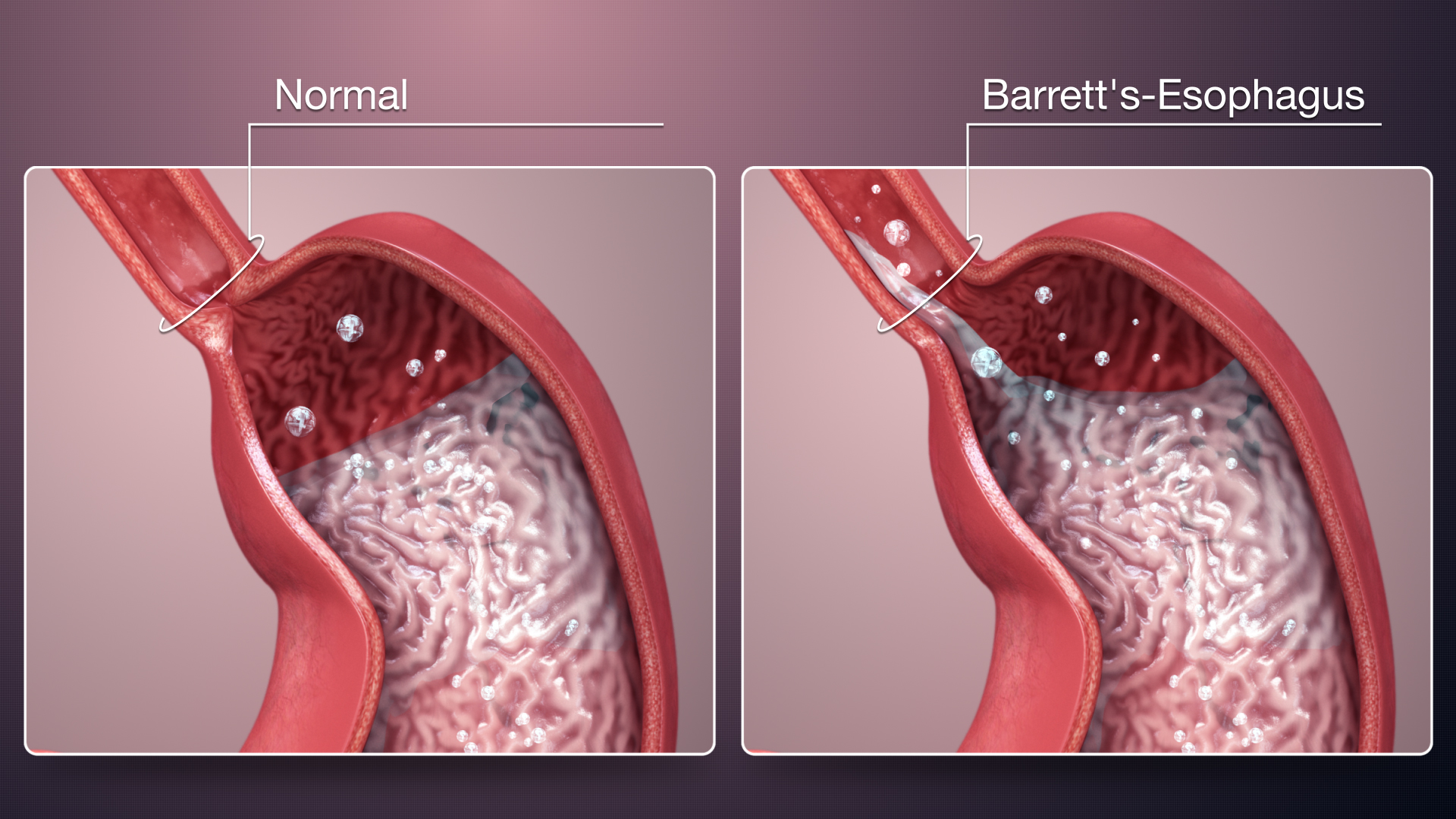

The primary cause of Barrett’s esophagus is chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter, a muscle that acts as a valve between the esophagus and stomach, becomes weak or relaxes inappropriately, allowing stomach acid to flow back into the esophagus. This acid reflux leads to irritation and inflammation of the esophageal lining over time, triggering changes in the tissue.

Additionally, obesity is strongly associated with the development of Barrett’s esophagus. Excess body weight increases intra-abdominal pressure, which can push stomach contents upward into the esophagus, exacerbating acid reflux.

Smoking is another risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus. Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter and reduces saliva production, which normally helps neutralize stomach acid in the esophagus.

A hiatal hernia, where a portion of the stomach protrudes through the diaphragm into the chest cavity, can also contribute to Barrett’s esophagus. This anatomical abnormality can disrupt the normal functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing acid reflux to occur more frequently.

Dietary factors may play a role as well. Consuming spicy, acidic, or fatty foods can exacerbate GERD symptoms and increase the likelihood of Barrett’s esophagus development.

Furthermore, genetic predisposition may contribute to an individual’s susceptibility to Barrett’s esophagus. Certain genetic factors may affect the function of the esophageal lining or the body’s response to acid reflux, influencing the development of this condition.

Overall, Barrett’s esophagus is a multifactorial condition influenced by a combination of lifestyle factors, anatomical abnormalities, and genetic predisposition. Understanding these causes is crucial for implementing preventive measures and managing the condition effectively. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Signs and Symptoms

Barrett’s esophagus often does not present with specific symptoms, and many individuals with the condition may remain asymptomatic. However, when symptoms do occur, they are typically associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which often precedes and accompanies Barrett’s esophagus.

Heartburn is one of the most common symptoms experienced by individuals with Barrett’s esophagus. It is characterized by a burning sensation in the chest, often occurring after meals or when lying down.

Regurgitation, where stomach contents flow back into the mouth or throat, is another common symptom of GERD and Barrett’s esophagus. This can lead to a sour or bitter taste in the mouth and may be accompanied by a sensation of fluid moving up the chest.

Difficulty swallowing, known as dysphagia, may also occur in individuals with Barrett’s esophagus. This symptom can range from a sensation of food getting stuck in the throat to pain or discomfort while swallowing.

Other symptoms associated with Barrett’s esophagus include:

- Chronic cough: Persistent coughing, particularly at night or after eating, can be a symptom of GERD and Barrett’s esophagus.

- Hoarseness: Irritation of the throat due to acid reflux can lead to hoarseness or changes in voice quality.

- Chest pain: While less common, some individuals with Barrett’s esophagus may experience chest pain that can mimic heart-related conditions.

- Unintentional weight loss: Severe or chronic GERD symptoms, including those associated with Barrett’s esophagus, may lead to decreased appetite and unintentional weight loss over time.

- Nausea and vomiting: In some cases, individuals with Barrett’s esophagus may experience nausea or vomiting, particularly after meals or when lying down.

Recognizing these signs and symptoms is important for prompt diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus and associated complications. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Etiology

The precise etiology of Barrett’s esophagus remains incompletely understood; however, several factors contribute to its development. Chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the primary underlying cause of Barrett’s esophagus. GERD occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a muscular valve between the esophagus and stomach, weakens or relaxes inappropriately, allowing stomach acid to reflux into the esophagus. This chronic exposure to gastric acid leads to inflammation and injury to the esophageal mucosa.

Obesity is a significant risk factor for the development of Barrett’s esophagus. Excessive body weight increases intra-abdominal pressure, which promotes the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. Additionally, adipose tissue secretes inflammatory cytokines that contribute to esophageal inflammation and injury.

Smoking is another established risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus. Cigarette smoke contains numerous toxic compounds that impair LES function and increase acid production in the stomach, exacerbating GERD symptoms.

A hiatal hernia, characterized by the protrusion of a portion of the stomach into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm, predisposes individuals to Barrett’s esophagus. Hiatal hernias disrupt the normal anatomy of the LES, facilitating acid reflux into the esophagus.

Dietary factors also play a role in the development of Barrett’s esophagus. Consumption of acidic, spicy, or fatty foods exacerbates GERD symptoms and contributes to esophageal mucosal injury.

Furthermore, genetic predisposition may influence an individual’s susceptibility to Barrett’s esophagus. Variations in genes involved in the regulation of esophageal mucosal integrity and inflammation may predispose individuals to develop Barrett’s esophagus in response to environmental triggers such as GERD.

Overall, Barrett’s esophagus is a multifactorial condition influenced by the interplay of genetic susceptibility, lifestyle factors, and environmental exposures, particularly chronic GERD. Understanding the etiological factors underlying Barrett’s esophagus is crucial for implementing preventive measures and optimizing therapeutic interventions. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of Barrett’s esophagus involves a series of cellular changes in response to chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The persistent exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acidic gastric contents leads to inflammation and injury, initiating a cascade of cellular events.

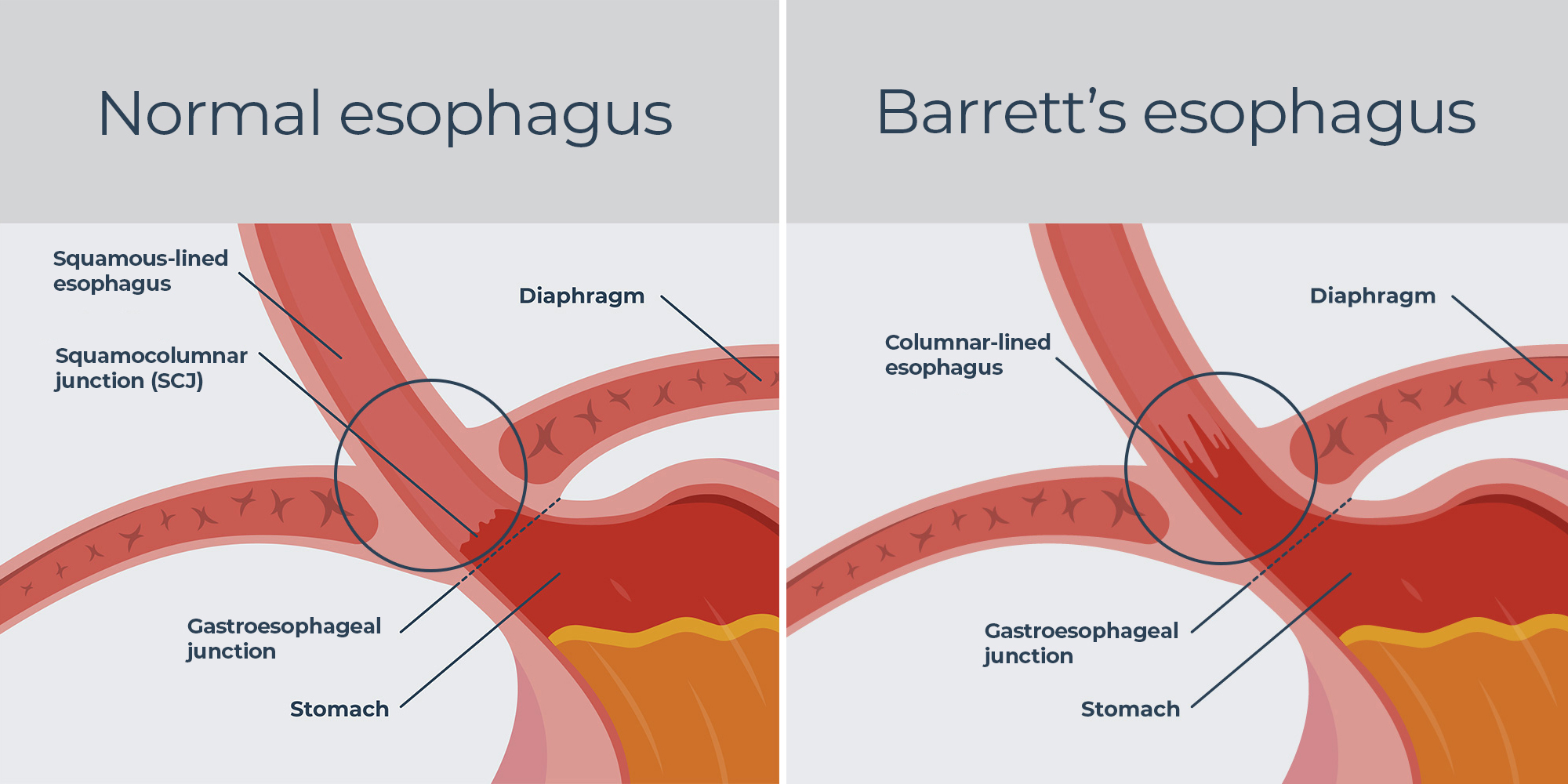

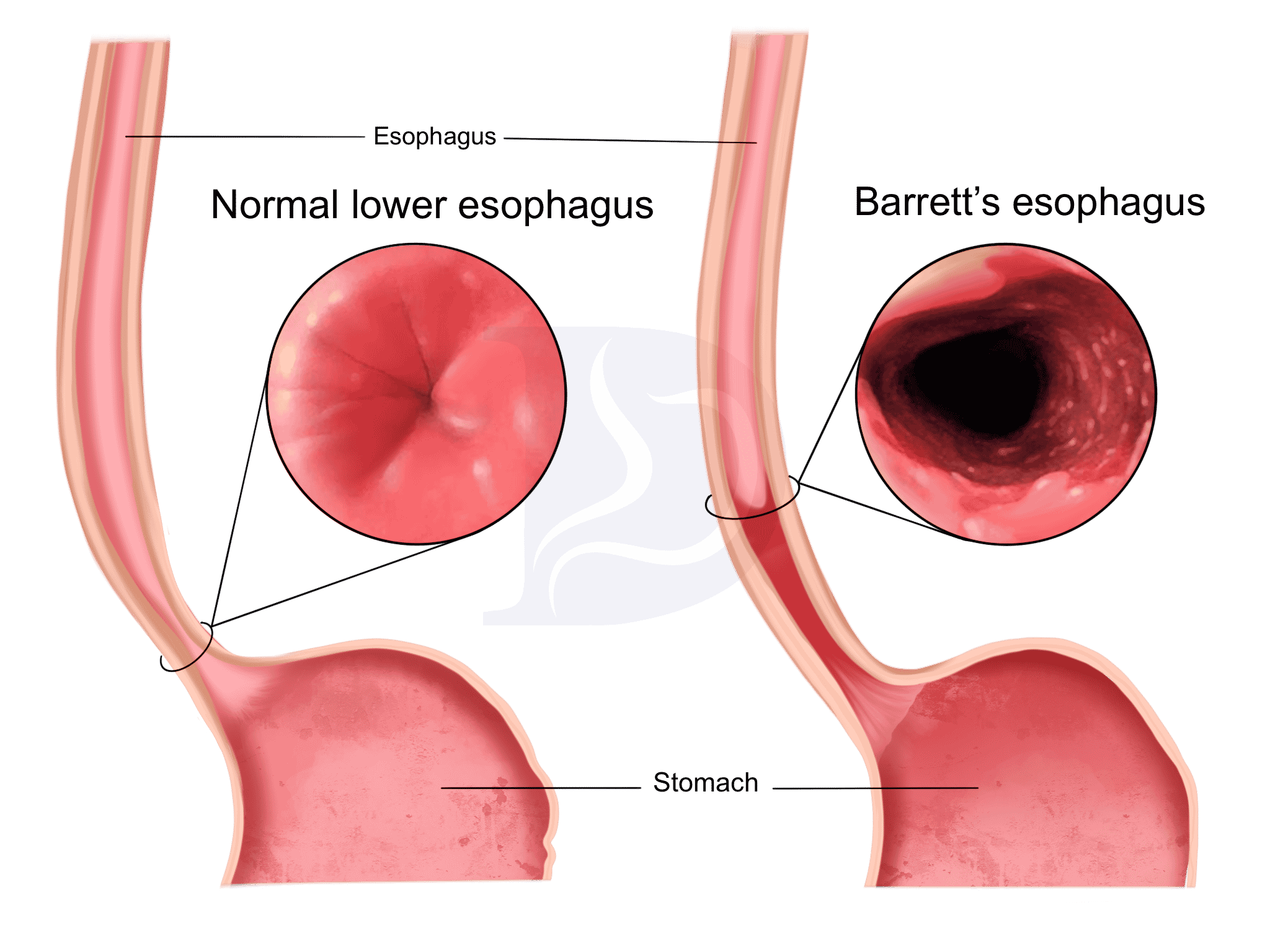

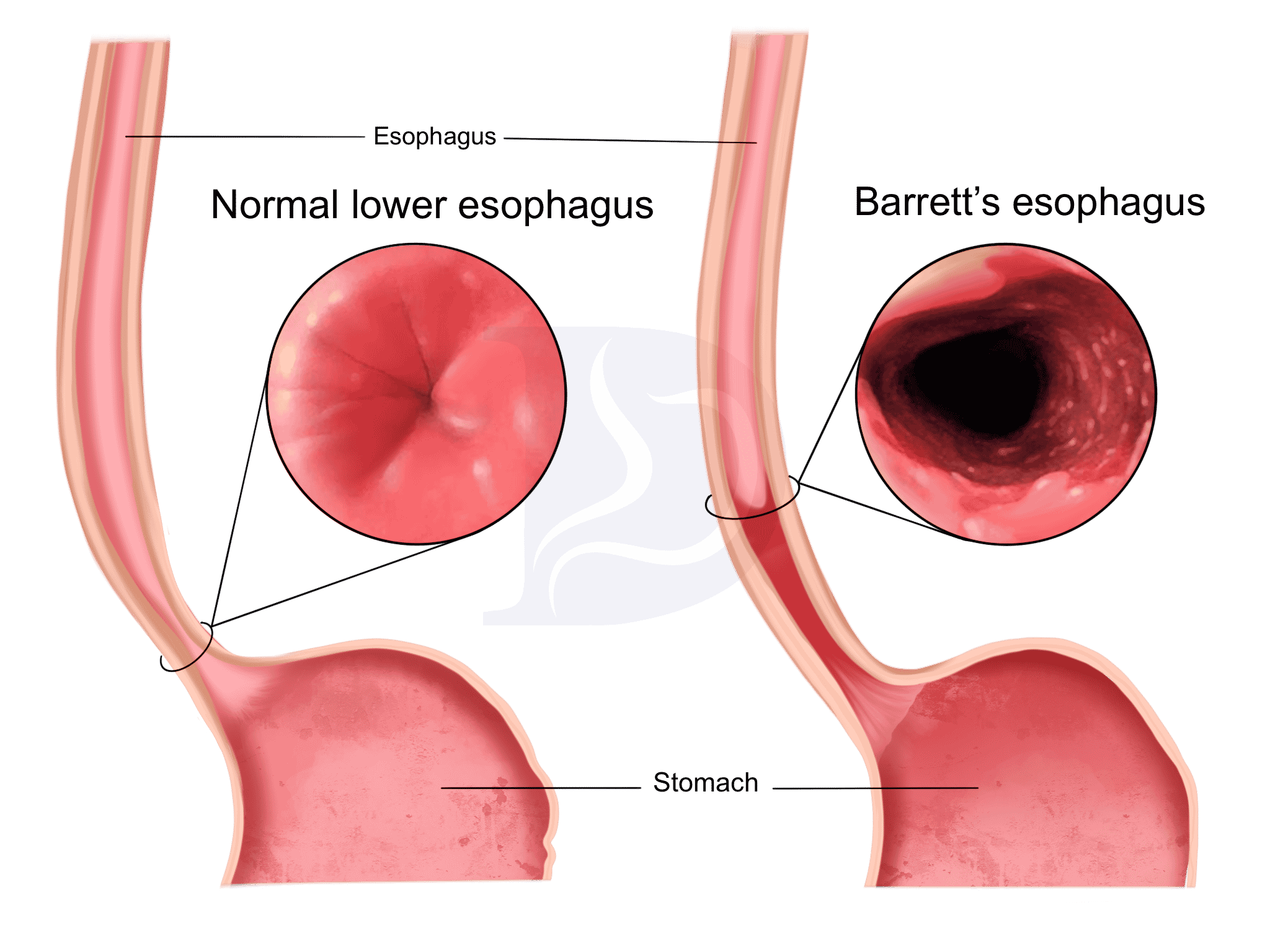

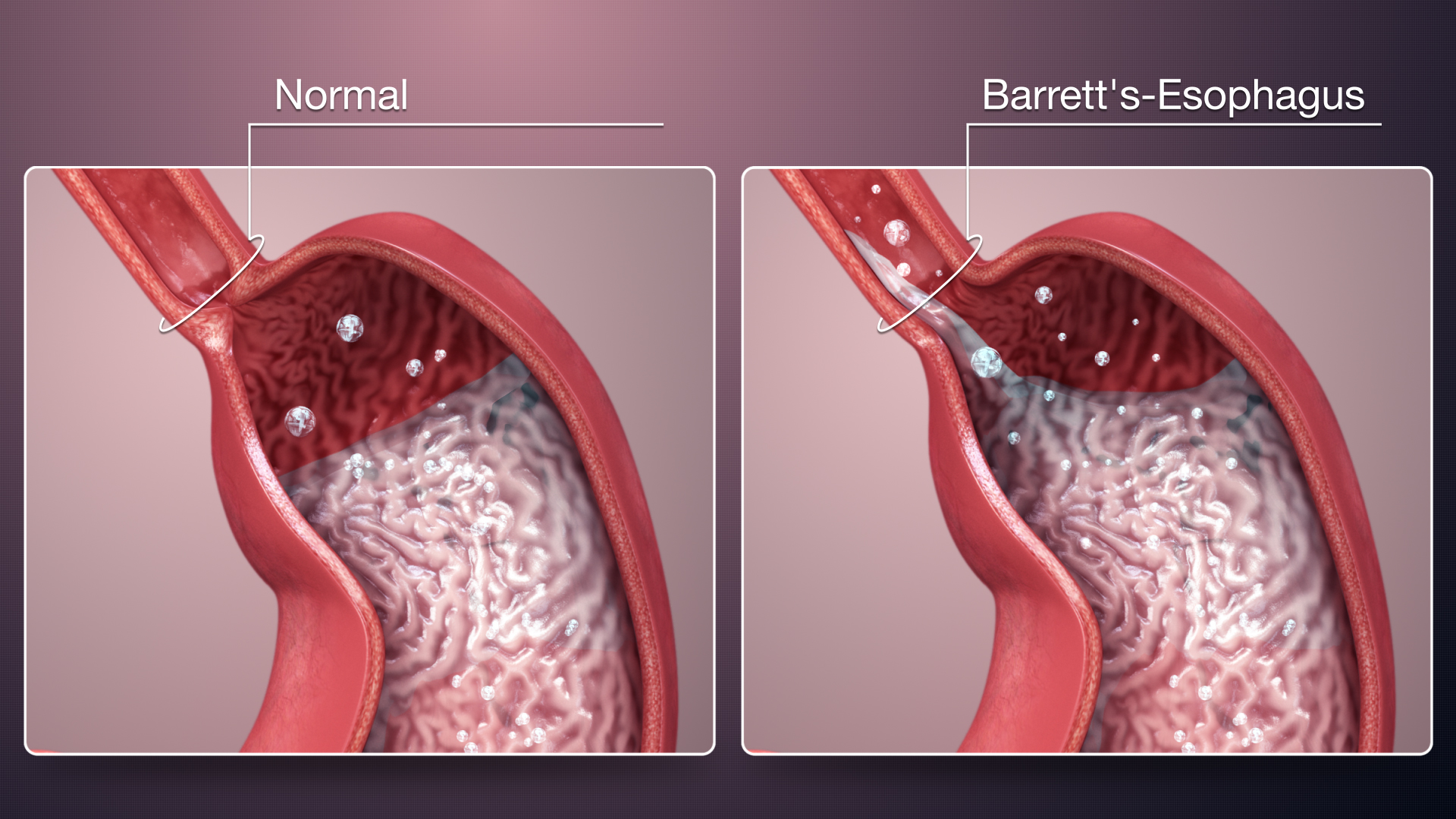

Initially, the normal stratified squamous epithelium lining the esophagus undergoes metaplastic changes in response to chronic acid exposure. This process, known as intestinal metaplasia, involves the replacement of squamous epithelial cells with specialized columnar epithelial cells resembling those found in the intestine. These columnar cells are more resistant to acid-induced injury but lack the protective mechanisms present in the stomach and intestine, rendering them vulnerable to further damage.

Over time, the metaplastic epithelium may progress to dysplasia, characterized by abnormal cellular growth and differentiation. Dysplastic changes can range from low-grade, characterized by mild cellular abnormalities, to high-grade, indicative of more severe cellular atypia. High-grade dysplasia is considered a precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma and represents a significant risk factor for cancer development.

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the progression from Barrett’s esophagus to adenocarcinoma are complex and multifactorial. Chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, genetic alterations, and dysregulated signaling pathways contribute to the malignant transformation of Barrett’s epithelium.

Ultimately, Barrett’s esophagus serves as a precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma, a lethal malignancy with a poor prognosis. Early detection and intervention are crucial for preventing cancer progression in individuals with Barrett’s esophagus.

Understanding the pathophysiology of Barrett’s esophagus provides insights into its clinical manifestations, complications, and therapeutic targets. Targeted interventions aimed at mitigating acid reflux, reducing inflammation, and inhibiting dysplastic progression may help prevent the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in individuals with Barrett’s esophagus. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

DMS-5 Diagnosis

Barrett’s esophagus is not a psychiatric disorder and thus not classified or diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Instead, the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is established through clinical evaluation and endoscopic examination with biopsy.

Clinical evaluation involves a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s medical history, including symptoms suggestive of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) such as heartburn, regurgitation, and difficulty swallowing. Additionally, the presence of risk factors such as obesity, smoking, and a history of hiatal hernia may raise suspicion for Barrett’s esophagus.

The definitive diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is made through upper endoscopy, also known as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). During this procedure, a flexible endoscope is passed through the mouth into the esophagus, allowing direct visualization of the esophageal mucosa. Characteristic findings suggestive of Barrett’s esophagus include the presence of salmon-pink or reddish mucosa extending into the esophagus, typically in the distal portion near the gastroesophageal junction.

Biopsies are obtained from suspicious areas of the esophageal mucosa during endoscopy to confirm the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus. Histopathological examination of these biopsies reveals the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia, characterized by the replacement of squamous epithelium with columnar epithelium containing goblet cells. Goblet cells are a hallmark feature of intestinal metaplasia and are not typically present in normal esophageal epithelium.

The diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is established based on the presence of intestinal metaplasia in the esophageal mucosa on histopathological examination of biopsy specimens obtained during endoscopy. Once diagnosed, regular surveillance endoscopy with biopsy is recommended to monitor for dysplastic changes and early detection of esophageal adenocarcinoma in individuals with Barrett’s esophagus. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Treatment Regimens and Patient Education

Treatment for Barrett’s esophagus focuses on managing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, reducing acid reflux, and preventing complications such as esophageal adenocarcinoma. Additionally, patient education plays a crucial role in empowering individuals to make lifestyle modifications and adhere to treatment regimens effectively.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus are advised to make several lifestyle modifications to reduce acid reflux and alleviate symptoms:

- Dietary Changes: Avoiding trigger foods such as spicy, acidic, or fatty foods can help reduce GERD symptoms. Eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding lying down immediately after eating can also minimize reflux.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight through diet and exercise is important, as obesity is a significant risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus and GERD.

- Smoking Cessation: Quitting smoking is essential, as smoking exacerbates GERD symptoms and increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Elevating the Head of the Bed: Sleeping with the head of the bed elevated can help reduce nighttime reflux.

Medications:

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): PPIs such as omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole are commonly prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and alleviate GERD symptoms. These medications help heal esophageal inflammation and may slow the progression of Barrett’s esophagus.

- Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonists: H2 blockers such as ranitidine and famotidine reduce stomach acid production and may be used in combination with PPIs for symptom management.

Surgical Interventions:

In some cases, surgical interventions may be considered to address severe GERD symptoms or complications of Barrett’s esophagus, such as dysplasia or early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma. Surgical procedures such as fundoplication aim to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter and prevent acid reflux.

Patient Education:

Patient education is crucial for promoting understanding, adherence to treatment regimens, and lifestyle modifications. Key aspects of patient education include:

- Understanding the Condition: Patients should be educated about the nature of Barrett’s esophagus, its association with GERD, and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Medication Adherence: Patients should be instructed on the importance of adhering to medication regimens, including PPIs, and informed about potential side effects and interactions.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Patients should receive guidance on dietary changes, weight management, smoking cessation, and other lifestyle modifications to minimize reflux and manage symptoms effectively.

- Importance of Surveillance: Patients with Barrett’s esophagus should understand the importance of regular surveillance endoscopy with biopsy for monitoring disease progression and detecting dysplasia or early-stage cancer.

By empowering patients with knowledge about their condition and providing guidance on lifestyle modifications and treatment regimens, healthcare providers can optimize outcomes and improve the quality of life for individuals with Barrett’s esophagus. (Nursing Paper Example on Barrett’s Esophagus: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment)

Conclusion

Do you need a similar assignment done for you from scratch? Order now!

Use Discount Code "Newclient" for a 15% Discount!